The Four Foundational Techniques of Traditional Chinese Martial Arts!

Translator's Note: I have retained the original Chinese language text for all our friends outside of China who are studying the written Chinese language - and for our Chinese language readers who live in areas where they cannot access the Mainland China internet link provided. The content mirrors exactly the manner in which Master Chan Tin Sang (1924-1993) conveyed the transmission of the Ch'an Dao (Mind Way) Hakka Chinese martial arts tradition to the West. Traditional Chinese martial arts are dangerous - but the dangerous elements are difficult to learn without the disciple possessing a good and virtuous character, a genuine teacher and a supportive community! These requirements form a protective barrier between those individuals with a corrupt character and the dangerous martial arts techniques (and methods) they could potentially learn and misuse! As matters stands, an arrogant and abusive opponent, depending upon the level of threat, could be kicked, punched, grappled or thrown to the ground! If the threat is of a greater danger, then dislocated and broken bones could be inflicted. In life-threatening situations where an armed (or unarmed) opponent seeks to kill his or her victims - then 'lethal' responses could well be deployed. This regretful situation would involve the breaking of bone, the dislocation of joints, the damaging of the internal organs and the fatal disruption of the flow of qi energy ('vital force') and blood! I have add considerably to the original text, providing relevant historical, cultural and medical background information where required. I have also expanded areas of the text where the subject matter might not be familiar to the average non-Chinese language reader. Being 'careful' is a major facet of traditional Chinese martial arts culture that should not be abandoned or driven underground by the unrealistic attitudes cultivated through the various versions of (modern) combat-derived martial sport! Life is a precious commodity that should be preserved at all costs, because once it is taken, it cannot be given back! ACW (4.9.2022)

INTRODUCTION

In order to achieve the goal of defeating an enemy, China as a nation has spent thousands of years perfecting unarmed and armed self-defence techniques. This article focuses upon the development of ‘unarmed’ martial arts practice in China which developed due to a long-term experience of hand-to-hand combat. The four foundational methods of fighting which eventually developed in China give full expression to the vigour and dynamism of various parts of the human body involved in their performance:

1) 打 (da3) - to hit, strike or slap, etc, with a closed or open hand. To use the hand vigorously!

2) 踢 (ti2) - to kick, stamp or sweep with the foot. To move the leg and foot vigorously!

3) 摔 (shuai1) - to throw, fling or cast away! To vigorously cause an enemy to lose balance and fall!

4) 拿 (na2) - to grasp, seize and hold! To vigorously restrict and constrict an enemy’s movement!

The cultural basis (or prototype) of these four Chinese martial arts skills is evident in the ancient Chinese text entitled the ‘Gongyang Treatise’ (公羊传 - Gong Yang Zhuan) - which serves as a ‘Commentary’ to the ‘Spring and Autumn Annals’ (春秋 - Chun Qiu) - the official historical record of the State of Lu. This covers a historical period of 241 years between 722-481 BCE. The ‘Gongyang Treatise’ is said to bear the name of its author - one ‘Gong Yang Gao’ (公羊高) who was from the State of Qi during the Warring States Period. It is believed that ‘Gong Yang Gao’ (公羊高) was the disciple of Master Zi Xia (子夏) - known historically as being an important disciple of Confucius (孔子 - Kong Zi). The ‘Gongyang Treatise’ describes the fighting of the time as being like wrestling and grappling, but involving the skilful use of the hand to strike, grip and parry, etc. There is discussion of a fight involving one of the protagonists ‘gripping’ the throat of another and literally ‘ripping’ or ‘tearing’ the throat structure out! We know from written descriptions like this, coupled with the general historical events of the time that China was a) a very violent and unpredictable place, and b) these conditions created people who were very good at being violent! This is the practical basis for the efficacy of Chinese martial arts techniques, but the historical period where the four basic skills are seen clearly, is during the Han Dynasty (202 BCE-220CE). These skills were further refined during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) and the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE). Indeed, recorded within the Ming Dynasty work of Qi Jiguang (戚继光) - particularly within his book entitled ‘New Treatise on Military Efficiency’ (纪效新书 - Ji Xiao Xin Shu) - there are the ‘kicking’ skills of one ‘Li Ban Shan’ or ‘Mid-Level Li’ (李半山) from Shandong! This is followed by one ‘Ying Zhao Wang’ or ‘Eagle Claw Wang’ (鹰爪王) who was good at ‘gripping’! Another name included is ‘Qian Die Zhang’ or ‘Thousand Falls Zhang’ (千跌张) who was good at ‘throwing’! Finally, there is ‘Zhang Bo Jing’ (张伯敬) or ‘Respectful Uncle Zhang’ who was renowned for his outstanding ‘punching’ skills!

In order to achieve the goal of defeating an enemy, China as a nation has spent thousands of years perfecting unarmed and armed self-defence techniques. This article focuses upon the development of ‘unarmed’ martial arts practice in China which developed due to a long-term experience of hand-to-hand combat. The four foundational methods of fighting which eventually developed in China give full expression to the vigour and dynamism of various parts of the human body involved in their performance:

1) 打 (da3) - to hit, strike or slap, etc, with a closed or open hand. To use the hand vigorously!

2) 踢 (ti2) - to kick, stamp or sweep with the foot. To move the leg and foot vigorously!

3) 摔 (shuai1) - to throw, fling or cast away! To vigorously cause an enemy to lose balance and fall!

4) 拿 (na2) - to grasp, seize and hold! To vigorously restrict and constrict an enemy’s movement!

The cultural basis (or prototype) of these four Chinese martial arts skills is evident in the ancient Chinese text entitled the ‘Gongyang Treatise’ (公羊传 - Gong Yang Zhuan) - which serves as a ‘Commentary’ to the ‘Spring and Autumn Annals’ (春秋 - Chun Qiu) - the official historical record of the State of Lu. This covers a historical period of 241 years between 722-481 BCE. The ‘Gongyang Treatise’ is said to bear the name of its author - one ‘Gong Yang Gao’ (公羊高) who was from the State of Qi during the Warring States Period. It is believed that ‘Gong Yang Gao’ (公羊高) was the disciple of Master Zi Xia (子夏) - known historically as being an important disciple of Confucius (孔子 - Kong Zi). The ‘Gongyang Treatise’ describes the fighting of the time as being like wrestling and grappling, but involving the skilful use of the hand to strike, grip and parry, etc. There is discussion of a fight involving one of the protagonists ‘gripping’ the throat of another and literally ‘ripping’ or ‘tearing’ the throat structure out! We know from written descriptions like this, coupled with the general historical events of the time that China was a) a very violent and unpredictable place, and b) these conditions created people who were very good at being violent! This is the practical basis for the efficacy of Chinese martial arts techniques, but the historical period where the four basic skills are seen clearly, is during the Han Dynasty (202 BCE-220CE). These skills were further refined during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE) and the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE). Indeed, recorded within the Ming Dynasty work of Qi Jiguang (戚继光) - particularly within his book entitled ‘New Treatise on Military Efficiency’ (纪效新书 - Ji Xiao Xin Shu) - there are the ‘kicking’ skills of one ‘Li Ban Shan’ or ‘Mid-Level Li’ (李半山) from Shandong! This is followed by one ‘Ying Zhao Wang’ or ‘Eagle Claw Wang’ (鹰爪王) who was good at ‘gripping’! Another name included is ‘Qian Die Zhang’ or ‘Thousand Falls Zhang’ (千跌张) who was good at ‘throwing’! Finally, there is ‘Zhang Bo Jing’ (张伯敬) or ‘Respectful Uncle Zhang’ who was renowned for his outstanding ‘punching’ skills!

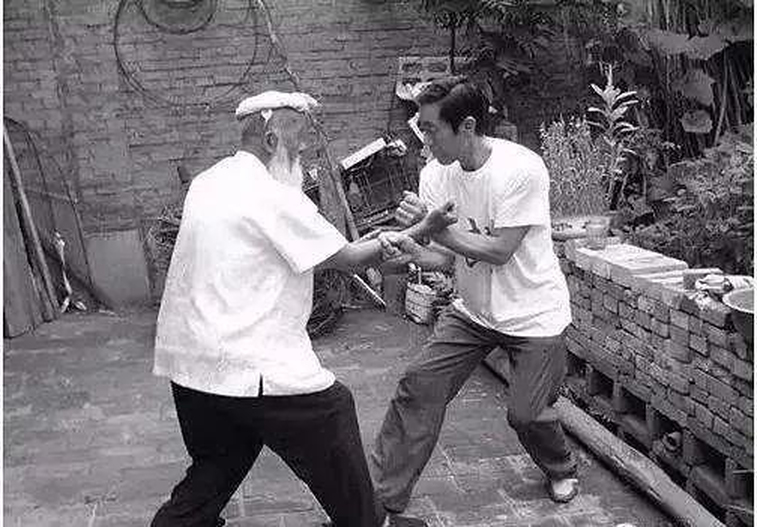

PART I) Strike Law (打法 - Da Fa)

Striking refers to unarmed and bear-handed hitting in any and all directions – using any part of the hand as an anatomical weapon. The definition can be extended to including any part of the wrist, fore-arm, elbow, upper-arm and shoulder, etc, including the front part of the skull (the ‘forehead’), providing all such striking is in support of the hands, and refers to the body above the waist (which must also be adequately ‘defended’ whilst being used as an offensive weapon). The effectiveness of the Law of Striking depends upon the skill-level of the exponent, their physical fitness, their weaknesses, their strengths, their personal circumstances and general situation. As human beings are highly intelligent, fighting tends to be a highly adaptive activity that is not limited to any set pattern or routine that can be predicted by an opponent. Each fighter develops a set of tactics which he or she must strategically apply successfully in an open combat situation! When free fighting, the prevailing combatant will be the one who applies the best tactics according to the situation. Striking effectively is premised upon the correct understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the human body. When hitting freely and effectively - it is best to use the eight strikes (八打 - Ba Da) - that must be mastered so that an opponent can be easily overpowered and subdued:

1) Striking the Eyebrows and Eyes (striking the eyebrow arch and the eyeball)

2) Striking the ‘Ren Zhong’ (人中) acupressure-point (situated between the nose and the upper lip)

3) Striking the Cheeks and Ears (hitting the acupressure points around the ear and along the Cheekbones)

4) Striking the Upper Back Points (hitting the acupressure points running along the outer ridge of the scapulae bone)

5) Striking the Ribcage (hitting the fixed ribs, the floating ribs, the gaps between the ribs and damaging the inner organs behind or near the ribs)

6) Striking the High Bone (hitting the pubic bone)

7) Striking the Crane Knee with the Tiger Head (a hardened fist punches downward into the patella – or kneecap)

8) Striking to Shatter Bones into a Thousand Pieces of Gold (breaking any bone or set of bones in the human body)

Chinese martial arts styles are countless in number and comprised of competing and contradictory histories, methods and purposes, etc, but one central point that all styles agree upon is the key principle of ‘adaptation’ (变 - Bian)! Kang Gewu (康戈武) - who compiled the ‘Practical Encyclopaedia of Chinese Martial Arts’ (中国武术实用大全 - Zhong Guo Wu Shu Shi Yong Da Quan) - states that the principle of ‘adaptability’ is comprised of three characteristics:

1) Immediate response. This is the ability to fight from contingency and to assess the situation as it unfolds. A direct-responsive approach must be adopted – one that does not possess the time to deploy any previous training tactics or strategies. An over-powering swift and direct response replaces a measured unfolding of controlled events to secure victory.

2) Adaptive response. This involves the ability to adapt and adjust in the face of the opponent’s deployment tactics and strategy. Essentially, this controls the opponent through ‘equalling’ and ‘negating’ the threat – prevent the opponent from winning whilst waiting for the opening (or ‘inconsistency’) in the opponent’s presentation that allows for a decisive technique to be applied that secures victory!

3) Leading response. An example of this can be found in the ancient book entitled ‘War Law’ (兵法 - Bing Fa) authored by the famous ‘Sunzi’ (孙子) - or ‘Master Sun’ and more widely known in the West as the ‘Art of War’. In the Chapter entitled ‘Void - Form’, Sunzi discusses the idea of the use of ‘void’ (虚 - Xu) and ‘form’ (实 - Shi) in conflict, as a means to mislead and confuse the opponent. The martial arts practitioner takes control of the encounter through the manipulation of the opponent’s perception – leading them to misinterpret events and make continuous and fatal errors in judgement. (What is deceptively made to appear ‘solid’ is empty – and what is deceptively made to appear ‘empty’ is full)!

Added to this body of knowledge is the ‘pre-emptive’ strike and the ‘retaliatory’ strike. The ‘pre-emptive’ strike seeks to initiate an attack upon an opponent BEFORE any conflict has started or the opponent has had any chance to initiate a violent exchange. A ‘pre-emptive’ strike is usually carried-out when advanced knowledge is gained of an opponent’s future intention to carry-out an attack. The initiative is suddenly snatched away from the opponent who is generally unprepared to meet this unexpected assault. A ‘retaliatory’ strike is a response to an unexpected or unprovoked attack. To be effective, the ‘retaliatory’ strike must be so decisive and over-powering that the advantage gained by the initial attack AND the ability of the opponent to violently respond - are both wiped-out in an instant and generally rendered ‘unrecoverable’! These ideas are premised upon the characteristics that define the Chinese nation. The Chinese character is good at concealing and does not like to reveal – prefers to keep hidden rather than make public. A preferred stillness can overcome unnecessary movement (through the application of expert countermovement), whilst a cultivated gentleness can envelop and negate an uncouth hardness! This is very different to the mentality that underlies the modern Boxing found in the West, which is continuously aggressive and prefers an ongoing attacking strategy time and time again! Compared to the narrow approach of Western fighting, within China there are countless styles of martial arts! Although all very different from one another on the surface, they all share the same underlying and unifying reality of being premised upon the expert use of ‘void’ and ‘form’ (虚实 - Xu Shi), as well as ‘stillness’ and ‘motion’! (动静 - Dong Jing). In reality, there is a continuous and relentless interchange occurring at the highest levels of Chinese martial arts mastery which sees the ‘real’ and the ‘seeming’ and the ‘Still’ and the ‘moving’ not only changing polarity continuously – but also acting interchangeably with one another! The ‘still’ and the ‘empty’ together with the ‘moving’ and the ‘full’ become synonymous with one another – whilst also becoming interconnected and immediately transferable! What appears abandoned is defended perfectly – and what appears defended perfectly has been abandoned, and so on!

Striking refers to unarmed and bear-handed hitting in any and all directions – using any part of the hand as an anatomical weapon. The definition can be extended to including any part of the wrist, fore-arm, elbow, upper-arm and shoulder, etc, including the front part of the skull (the ‘forehead’), providing all such striking is in support of the hands, and refers to the body above the waist (which must also be adequately ‘defended’ whilst being used as an offensive weapon). The effectiveness of the Law of Striking depends upon the skill-level of the exponent, their physical fitness, their weaknesses, their strengths, their personal circumstances and general situation. As human beings are highly intelligent, fighting tends to be a highly adaptive activity that is not limited to any set pattern or routine that can be predicted by an opponent. Each fighter develops a set of tactics which he or she must strategically apply successfully in an open combat situation! When free fighting, the prevailing combatant will be the one who applies the best tactics according to the situation. Striking effectively is premised upon the correct understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the human body. When hitting freely and effectively - it is best to use the eight strikes (八打 - Ba Da) - that must be mastered so that an opponent can be easily overpowered and subdued:

1) Striking the Eyebrows and Eyes (striking the eyebrow arch and the eyeball)

2) Striking the ‘Ren Zhong’ (人中) acupressure-point (situated between the nose and the upper lip)

3) Striking the Cheeks and Ears (hitting the acupressure points around the ear and along the Cheekbones)

4) Striking the Upper Back Points (hitting the acupressure points running along the outer ridge of the scapulae bone)

5) Striking the Ribcage (hitting the fixed ribs, the floating ribs, the gaps between the ribs and damaging the inner organs behind or near the ribs)

6) Striking the High Bone (hitting the pubic bone)

7) Striking the Crane Knee with the Tiger Head (a hardened fist punches downward into the patella – or kneecap)

8) Striking to Shatter Bones into a Thousand Pieces of Gold (breaking any bone or set of bones in the human body)

Chinese martial arts styles are countless in number and comprised of competing and contradictory histories, methods and purposes, etc, but one central point that all styles agree upon is the key principle of ‘adaptation’ (变 - Bian)! Kang Gewu (康戈武) - who compiled the ‘Practical Encyclopaedia of Chinese Martial Arts’ (中国武术实用大全 - Zhong Guo Wu Shu Shi Yong Da Quan) - states that the principle of ‘adaptability’ is comprised of three characteristics:

1) Immediate response. This is the ability to fight from contingency and to assess the situation as it unfolds. A direct-responsive approach must be adopted – one that does not possess the time to deploy any previous training tactics or strategies. An over-powering swift and direct response replaces a measured unfolding of controlled events to secure victory.

2) Adaptive response. This involves the ability to adapt and adjust in the face of the opponent’s deployment tactics and strategy. Essentially, this controls the opponent through ‘equalling’ and ‘negating’ the threat – prevent the opponent from winning whilst waiting for the opening (or ‘inconsistency’) in the opponent’s presentation that allows for a decisive technique to be applied that secures victory!

3) Leading response. An example of this can be found in the ancient book entitled ‘War Law’ (兵法 - Bing Fa) authored by the famous ‘Sunzi’ (孙子) - or ‘Master Sun’ and more widely known in the West as the ‘Art of War’. In the Chapter entitled ‘Void - Form’, Sunzi discusses the idea of the use of ‘void’ (虚 - Xu) and ‘form’ (实 - Shi) in conflict, as a means to mislead and confuse the opponent. The martial arts practitioner takes control of the encounter through the manipulation of the opponent’s perception – leading them to misinterpret events and make continuous and fatal errors in judgement. (What is deceptively made to appear ‘solid’ is empty – and what is deceptively made to appear ‘empty’ is full)!

Added to this body of knowledge is the ‘pre-emptive’ strike and the ‘retaliatory’ strike. The ‘pre-emptive’ strike seeks to initiate an attack upon an opponent BEFORE any conflict has started or the opponent has had any chance to initiate a violent exchange. A ‘pre-emptive’ strike is usually carried-out when advanced knowledge is gained of an opponent’s future intention to carry-out an attack. The initiative is suddenly snatched away from the opponent who is generally unprepared to meet this unexpected assault. A ‘retaliatory’ strike is a response to an unexpected or unprovoked attack. To be effective, the ‘retaliatory’ strike must be so decisive and over-powering that the advantage gained by the initial attack AND the ability of the opponent to violently respond - are both wiped-out in an instant and generally rendered ‘unrecoverable’! These ideas are premised upon the characteristics that define the Chinese nation. The Chinese character is good at concealing and does not like to reveal – prefers to keep hidden rather than make public. A preferred stillness can overcome unnecessary movement (through the application of expert countermovement), whilst a cultivated gentleness can envelop and negate an uncouth hardness! This is very different to the mentality that underlies the modern Boxing found in the West, which is continuously aggressive and prefers an ongoing attacking strategy time and time again! Compared to the narrow approach of Western fighting, within China there are countless styles of martial arts! Although all very different from one another on the surface, they all share the same underlying and unifying reality of being premised upon the expert use of ‘void’ and ‘form’ (虚实 - Xu Shi), as well as ‘stillness’ and ‘motion’! (动静 - Dong Jing). In reality, there is a continuous and relentless interchange occurring at the highest levels of Chinese martial arts mastery which sees the ‘real’ and the ‘seeming’ and the ‘Still’ and the ‘moving’ not only changing polarity continuously – but also acting interchangeably with one another! The ‘still’ and the ‘empty’ together with the ‘moving’ and the ‘full’ become synonymous with one another – whilst also becoming interconnected and immediately transferable! What appears abandoned is defended perfectly – and what appears defended perfectly has been abandoned, and so on!

PART II) Gripping Law (拿法 - Na Fa)

Gripping refers to the art of ‘Qinna’ (擒拿) or the painful ‘catching and holding’ of the bones and joints of an opponent. Maximum pain (and discomfort) is caused by the use of the fingertips which powerfully press the various acupressure points – whilst fingers and palm restrict (and constrict) the various joints – manipulating the bones, ligaments (which surround joints and hold bones to bones), tendons (which attach muscles to bones) and the muscle themselves, as the joints are expertly twisted, pressed and lifted out of their natural alignment and anatomical position, causing a dislocation. When the points are pressed, and a joint is levered (or twisted) back upon itself (just prior to dislocation), so much pain is suffered that fighting immediately stops and the opponent can be manoeuvred around and rendered harmless. If the struggle continues, however, then the full dislocation can be applied. There is written evidence of the existence of ‘catching and holding’ during the Ming Dynasty in the book entitled ‘Jiangnan Defence of the Border’ (江南经略 - Jiang Nan Jing Jue) - a text written by the Ming military strategist – Zheng Ruoceng (郑若曾) - concerning the defence of the Chinese realm lying South of the Yangtze River (‘Jiangnan’) against attack from organised Japanese pirates! Whilst assessing the strengths of the Chinese nation, the methodology of ‘Qinna’ (擒拿) is described as consisting of thirty-six types of ‘gripping’ and ‘holding’ (拿 - Na) bones and joints and thirty-six types of ‘breaking’ (解 - Jie) bones and joints. Today, with the development of competition this type of fighting is rarely seen in public – although a watered-down ‘sport’ variant is taught that ‘catches’ and ‘holds’ an opponent until voluntary submission! Occasionally in Asia, an expert in the old version of this martial art becomes well-known for catching a criminal!

The grappling method consists of two techniques – a) applying the hold and b) countering the hold. Applying the hold is comprised of three aspects:

1) Gripping the bone:

This technique is designed to cause damage to the large and small bones, as well as the joints of the body. The clavicle, rib cage and the phalanges, etc, are typical target areas. The technique of sudden twisting, over-twisting and twisting the wrong way is employed. The pain this causes the opponent should be intense. Such action should lead to dislocated joints and broken bones. The main types of grips used to hold the bones consist of:

a) To grip by ‘digging’ (挖 - Wa)

b) To grip by ‘relocating’ (搬 - Ban)

c) To grip by ‘restraining’ (扣 - Kou)

d) To grip by ‘constriction’ (捏 - Nie)

These are the methods used to secure victory through gripping the bone!

2) Gripping the tendon.

Gripping the tendon is also gripping the muscle. The four fingers and thumb grip the muscle mass and immediately locate the tendons (holding the muscle to the bone), and the ligaments (which secure one bone to another and enwrap a joint). Tendons can be ‘over-stretched’ (strained) and ligaments can be over-stretched (sprained) whilst the muscle mass can be bruised. This is the least damage that can be achieved. The most severe damage involves the breaking of the tendons from the bone-attachment or from the muscle mass – whilst the ligaments can be ‘disconnected’ from their bone-attachments! The protective membranes of the joints can be ruptured releasing synovial fluid, etc. There are ten ways to ‘grip’ a tendon:

a) Grip by ‘scratching’ (抓 - Zhua)

b) Grip by ‘Pinching’ (捏 - Nie)

c) Grip by ‘Lifting’ (提 - Ti)

d) Grip by ‘Opposing’ (抗 - Kang/0

e) Grip by ‘Digging’ (挖 - Wa)

f) Grip by ‘Closing’ (合 - He)

g) Grip by ‘Plucking’ (摘 - Zhai)

h) Grip by ‘Trapping’ (卡 - Ka)

i) Grip by ‘Pulling’ (揪 - Jiu)

j) Grip by ‘Scooping’ (顶 - Ding)

These are the methods used to secure victory through gripping the tendons!

3) Gripping (and applying intense force) to the acupressure points.

The essence of human life is dependent upon the continued and efficient flow of ‘qi’ (气) and ‘blood’ (血 - Xue)! Both ‘qi’ and ‘blood’ must flow through the human body and never become stagnant or stand still. This is why ‘qi’ and ‘blood’ flow must never become ‘blocked’, ‘constricted’ or ‘hindered’ in any way! If blocked or constricted in a superficial sense, the ability to move about and exercise becomes restricted – whilst if blocked in a deep sense, then loss of life will occur! The acupuncture method of fighting involves the powerful ‘gripping’ and ‘pressing’ of the opponent’s important acupoints which ‘blocks’ or ‘restricts’ the ‘qi’ and ‘blood’ flow! In a superficial sense, when applied properly this prevents the opponent from moving his or her limbs properly. This is why acupressure striking is known as the ‘Crown of Qinna’ (擒拿之冠 - Qin Na Zhi Guan)! Commonly used acupuncture points include:

a) 厥阴 (Jue Yin) - Meridian Point - Bladder 14 - Located on the back, level with the lower border of the spinous process of the 4th thoracic vertebra, 5 cm lateral to the posterior midline.

b) 眉心 (Mei Xin) - Centre point between the eyebrows (synonymous with the ‘third-eye’ location). The exact same position as the extra TCM point known as ‘Yin Tang’ (印堂).

c) 承山 (Cheng Shan) - Meridian Point - Urinary Bladder UB57 - Located in the centre of the base of the calf muscle, midway between the crease behind the knee and the heel, at the bottom of the calf muscle bulge.

d) 合谷 - (He Gu) - Meridian Point – Large Intestine LI14 - Located on the dorsum of the hand, midway between the 1st and 2nd metacarpal bones, approximately in the middle of the 2nd metacarpal bone on the radial side.

e) 曲池 - (Qu Chi) - Meridian Point – Large Intestine – LI11 – Located on the outside end of the crease on the elbow.

f) 气位 - (Qi Wei) - Literally ‘Qi Location’ – and involves the striking of the body in different ways at certain times of the day or night, and different times throughout the year as the seasons change. The Qi (and blood) flow varies in its intensity, distribution and balance regard to ‘Yin’ (陰) and ‘Yang’ (陽) throughout the times of the day and times of year.

h) 麻穴 - (Ma Xue) - Meridian Point – Small Intestine – SI3 – When a loose fist is made, the point is on the ulnar aspect of the hand, proximal to the 5th metacarpophalangeal joint, at the end of the transverse crease of the metacarpophalangeal joint - at the junction of the red and white skin.

i) 痛穴 - (Tong Xue) - Two pressure points located on the back of the hand, between the 2nd and 3rd metacarpal bones and the 4th and 5th metacarpal bones. Situated 5 cm above the wrist crease – and the midpoint – 5 cm below the metacarpophalangeal joint.

j) 晕穴 - (Yun Xue) - Meridian Point – Governing Vessel – GV 20 – located at the exact centre of the top of the head.

k) 哑穴 - (Ya Xue) - Meridian Points – Stomach – St9 & St10 - Located parallel to the carotid artery running up each side of neck – and to the left and right of the oesophagus through which water and food pass. On the neck, lateral to the Adam's apple, on the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoideus muscle.

The ‘Qinna’ (擒拿) method of effectively ‘seizing’ and ‘holding’ is very complex and technical - requiring quickness and accuracy. Furthermore, genuine ‘Qinna’ requires the complete mastery of the ‘external’ (外 - Wai) and ‘internal’ (内 - Nei) generation and application of strength. A ‘Qinna’ practitioner must be both ‘fast’, adaptable and deadly ‘accurate’ when deploying the ‘seizing’ and ‘holding’ techniques so that the opponent has no opportunity to evade the attack! This is why there are four basic principles that define ‘Qinna’ training:

1) Seize and control each targeted pressure-point without hesitation.

2) Prevail by controlling the opponent and applying superior skill.

3) Within ‘movement’ there is ‘stillness’ - within ‘stillness’ there is ‘movement’.

4) Each secure hold must break a bone or joint – whilst a broken bone or joint ensures a secure hold!

For every ‘Qinna’ application – there exists a counter technique! If a part of my body is seized by a ‘Qinna’ expert - I should know how to negate the hold! There are many counter measures to be learned, but generally they are divided into two categories:

a) If an opponent ‘seizes’ any part of my body – I automatically seize a part his or her body!

b) If I am ‘seized’ - I attack the seizing hand and limb to ‘break’ the hold!

There are various styles of applying ‘Qinna’ grips and holds – just as there are many styles of ‘Qinna’ counter measures! Every dangerous ‘Qinna’ hold contains within itself its own negation! Qinna can be practiced alone or in pairs depending upon the situation.

Gripping refers to the art of ‘Qinna’ (擒拿) or the painful ‘catching and holding’ of the bones and joints of an opponent. Maximum pain (and discomfort) is caused by the use of the fingertips which powerfully press the various acupressure points – whilst fingers and palm restrict (and constrict) the various joints – manipulating the bones, ligaments (which surround joints and hold bones to bones), tendons (which attach muscles to bones) and the muscle themselves, as the joints are expertly twisted, pressed and lifted out of their natural alignment and anatomical position, causing a dislocation. When the points are pressed, and a joint is levered (or twisted) back upon itself (just prior to dislocation), so much pain is suffered that fighting immediately stops and the opponent can be manoeuvred around and rendered harmless. If the struggle continues, however, then the full dislocation can be applied. There is written evidence of the existence of ‘catching and holding’ during the Ming Dynasty in the book entitled ‘Jiangnan Defence of the Border’ (江南经略 - Jiang Nan Jing Jue) - a text written by the Ming military strategist – Zheng Ruoceng (郑若曾) - concerning the defence of the Chinese realm lying South of the Yangtze River (‘Jiangnan’) against attack from organised Japanese pirates! Whilst assessing the strengths of the Chinese nation, the methodology of ‘Qinna’ (擒拿) is described as consisting of thirty-six types of ‘gripping’ and ‘holding’ (拿 - Na) bones and joints and thirty-six types of ‘breaking’ (解 - Jie) bones and joints. Today, with the development of competition this type of fighting is rarely seen in public – although a watered-down ‘sport’ variant is taught that ‘catches’ and ‘holds’ an opponent until voluntary submission! Occasionally in Asia, an expert in the old version of this martial art becomes well-known for catching a criminal!

The grappling method consists of two techniques – a) applying the hold and b) countering the hold. Applying the hold is comprised of three aspects:

1) Gripping the bone:

This technique is designed to cause damage to the large and small bones, as well as the joints of the body. The clavicle, rib cage and the phalanges, etc, are typical target areas. The technique of sudden twisting, over-twisting and twisting the wrong way is employed. The pain this causes the opponent should be intense. Such action should lead to dislocated joints and broken bones. The main types of grips used to hold the bones consist of:

a) To grip by ‘digging’ (挖 - Wa)

b) To grip by ‘relocating’ (搬 - Ban)

c) To grip by ‘restraining’ (扣 - Kou)

d) To grip by ‘constriction’ (捏 - Nie)

These are the methods used to secure victory through gripping the bone!

2) Gripping the tendon.

Gripping the tendon is also gripping the muscle. The four fingers and thumb grip the muscle mass and immediately locate the tendons (holding the muscle to the bone), and the ligaments (which secure one bone to another and enwrap a joint). Tendons can be ‘over-stretched’ (strained) and ligaments can be over-stretched (sprained) whilst the muscle mass can be bruised. This is the least damage that can be achieved. The most severe damage involves the breaking of the tendons from the bone-attachment or from the muscle mass – whilst the ligaments can be ‘disconnected’ from their bone-attachments! The protective membranes of the joints can be ruptured releasing synovial fluid, etc. There are ten ways to ‘grip’ a tendon:

a) Grip by ‘scratching’ (抓 - Zhua)

b) Grip by ‘Pinching’ (捏 - Nie)

c) Grip by ‘Lifting’ (提 - Ti)

d) Grip by ‘Opposing’ (抗 - Kang/0

e) Grip by ‘Digging’ (挖 - Wa)

f) Grip by ‘Closing’ (合 - He)

g) Grip by ‘Plucking’ (摘 - Zhai)

h) Grip by ‘Trapping’ (卡 - Ka)

i) Grip by ‘Pulling’ (揪 - Jiu)

j) Grip by ‘Scooping’ (顶 - Ding)

These are the methods used to secure victory through gripping the tendons!

3) Gripping (and applying intense force) to the acupressure points.

The essence of human life is dependent upon the continued and efficient flow of ‘qi’ (气) and ‘blood’ (血 - Xue)! Both ‘qi’ and ‘blood’ must flow through the human body and never become stagnant or stand still. This is why ‘qi’ and ‘blood’ flow must never become ‘blocked’, ‘constricted’ or ‘hindered’ in any way! If blocked or constricted in a superficial sense, the ability to move about and exercise becomes restricted – whilst if blocked in a deep sense, then loss of life will occur! The acupuncture method of fighting involves the powerful ‘gripping’ and ‘pressing’ of the opponent’s important acupoints which ‘blocks’ or ‘restricts’ the ‘qi’ and ‘blood’ flow! In a superficial sense, when applied properly this prevents the opponent from moving his or her limbs properly. This is why acupressure striking is known as the ‘Crown of Qinna’ (擒拿之冠 - Qin Na Zhi Guan)! Commonly used acupuncture points include:

a) 厥阴 (Jue Yin) - Meridian Point - Bladder 14 - Located on the back, level with the lower border of the spinous process of the 4th thoracic vertebra, 5 cm lateral to the posterior midline.

b) 眉心 (Mei Xin) - Centre point between the eyebrows (synonymous with the ‘third-eye’ location). The exact same position as the extra TCM point known as ‘Yin Tang’ (印堂).

c) 承山 (Cheng Shan) - Meridian Point - Urinary Bladder UB57 - Located in the centre of the base of the calf muscle, midway between the crease behind the knee and the heel, at the bottom of the calf muscle bulge.

d) 合谷 - (He Gu) - Meridian Point – Large Intestine LI14 - Located on the dorsum of the hand, midway between the 1st and 2nd metacarpal bones, approximately in the middle of the 2nd metacarpal bone on the radial side.

e) 曲池 - (Qu Chi) - Meridian Point – Large Intestine – LI11 – Located on the outside end of the crease on the elbow.

f) 气位 - (Qi Wei) - Literally ‘Qi Location’ – and involves the striking of the body in different ways at certain times of the day or night, and different times throughout the year as the seasons change. The Qi (and blood) flow varies in its intensity, distribution and balance regard to ‘Yin’ (陰) and ‘Yang’ (陽) throughout the times of the day and times of year.

h) 麻穴 - (Ma Xue) - Meridian Point – Small Intestine – SI3 – When a loose fist is made, the point is on the ulnar aspect of the hand, proximal to the 5th metacarpophalangeal joint, at the end of the transverse crease of the metacarpophalangeal joint - at the junction of the red and white skin.

i) 痛穴 - (Tong Xue) - Two pressure points located on the back of the hand, between the 2nd and 3rd metacarpal bones and the 4th and 5th metacarpal bones. Situated 5 cm above the wrist crease – and the midpoint – 5 cm below the metacarpophalangeal joint.

j) 晕穴 - (Yun Xue) - Meridian Point – Governing Vessel – GV 20 – located at the exact centre of the top of the head.

k) 哑穴 - (Ya Xue) - Meridian Points – Stomach – St9 & St10 - Located parallel to the carotid artery running up each side of neck – and to the left and right of the oesophagus through which water and food pass. On the neck, lateral to the Adam's apple, on the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoideus muscle.

The ‘Qinna’ (擒拿) method of effectively ‘seizing’ and ‘holding’ is very complex and technical - requiring quickness and accuracy. Furthermore, genuine ‘Qinna’ requires the complete mastery of the ‘external’ (外 - Wai) and ‘internal’ (内 - Nei) generation and application of strength. A ‘Qinna’ practitioner must be both ‘fast’, adaptable and deadly ‘accurate’ when deploying the ‘seizing’ and ‘holding’ techniques so that the opponent has no opportunity to evade the attack! This is why there are four basic principles that define ‘Qinna’ training:

1) Seize and control each targeted pressure-point without hesitation.

2) Prevail by controlling the opponent and applying superior skill.

3) Within ‘movement’ there is ‘stillness’ - within ‘stillness’ there is ‘movement’.

4) Each secure hold must break a bone or joint – whilst a broken bone or joint ensures a secure hold!

For every ‘Qinna’ application – there exists a counter technique! If a part of my body is seized by a ‘Qinna’ expert - I should know how to negate the hold! There are many counter measures to be learned, but generally they are divided into two categories:

a) If an opponent ‘seizes’ any part of my body – I automatically seize a part his or her body!

b) If I am ‘seized’ - I attack the seizing hand and limb to ‘break’ the hold!

There are various styles of applying ‘Qinna’ grips and holds – just as there are many styles of ‘Qinna’ counter measures! Every dangerous ‘Qinna’ hold contains within itself its own negation! Qinna can be practiced alone or in pairs depending upon the situation.

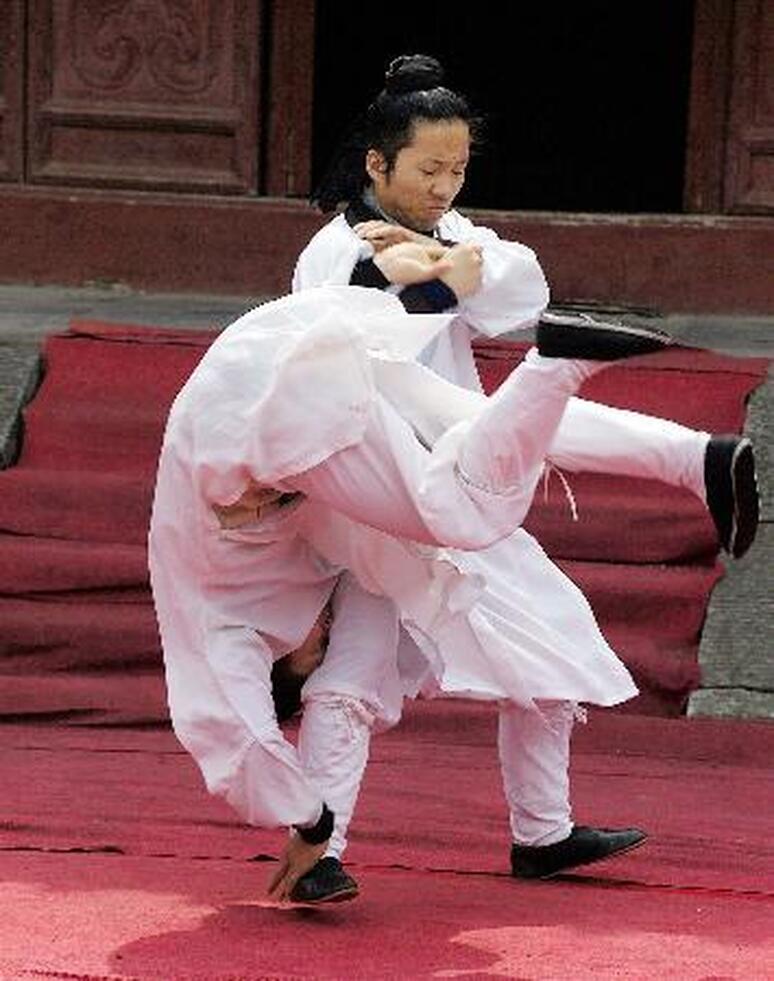

PART III) Throwing Law (摔法 - Shuai – Fa)

An old Chinese martial arts proverb says, ‘When fist-fighting is combined with wrestling – its potency is enhanced!’

The art of wrestling is also known as the art of ‘dropping’ (跌 - Die) an opponent! Throwing an opponent is the sudden ability of ‘uprooting’ and ‘pushing’ an opponent (with tremendous force) into the ground or against an object in the environment! The force of the ‘drop’ and ‘impact’ is designed to render the opponent ‘unconscious’ and to ‘break ‘bones’ and ‘dislocate’ joints! A perfectly executed throw can ‘kill’ an opponent due to the collision of the skull with the ground (or some other object). However, as a throw might not cause substantial damage, the wrestler will rain down punches, kicks, as well as elbow and knee strikes - until unconsciousness or death occurs in the opponent! At the very least, the Wrestler seeks to subdue the opponent.

The underlying principle of wrestling involves the ‘uprooting’ of an opponent through the clever use of leverage and pivotal force. Acting with an expert swiftness, the wrestler carries out a unified attack upon the opponent by entering into his or her defensive zone, making physical contact with the opponent’s body, and apply massive but highly concise and directed force to just the right spot! This is the ‘pivot’ - usually comprised of a set of bones and joint – into which force is applied, and over which the opponent will be thrown! Any part of the opponent’s body can be used in theory as a ‘fulcrum’ through which a throw can be applied. Obviously, with ‘neck’ the vertebrae will be broken, and death or permanent paralysis will result. Furthermore, a throw involving the legs or waist as the pivot can also lead to the opponent ‘dropping’ upon their head and breaking their neck in a similar fashion!

There are many ways to throw an opponent:

a) Hooking the Foot. The foot acts as the primary fulcrum whilst a damaging hold is simultaneously applied to the knee or elbow.

b) Impacting the Back. The back area of the opponent is used as a pivot – whilst being struck with a force that lifts the opponent off their feet! The opponent hits the ground backwards!

c) Catching Leg Attack. The opponent is thrown after their kicking leg is caught and their supporting leg is hooked off the ground! A dislocating hold is applied to the captured knee area through twisting, smashing, dropping or rising, etc.

d) Hanging Attack: The feet and legs are impacted backwards into the air – behind the opponent – so that he or she must ‘hang’ over the body of the attacker with their hands supporting their weight by touching the ground!

e) Upper Arm Attack. Placing the fulcrum (with speed and power) between the upper arm and the body of the opponent will cause an ‘uprooting’ to occur.

f) Pull and Twist. By securing elbow (and the arm either side) a twisting action causes the opponent to easily roll over an applied fulcrum.

g) Blocked Leg Attack. When the opponent attempts to take a step – the wrestler ‘blocks’ or ‘jams’ their feet, lower or upper leg sections so that their leg stops moving whilst their momentum continues to move! The ‘blocked’ leg becomes the fulcrum over which the opponent falls.

h) Piercing the Groin. By placing an arm between the legs of the opponent directly adjacent to the groin area, one of the opponent’s legs is secured for uprooting, twisting or displacing. By placing the entire body into the groinal area the opponent may be lifted and thrown. A variant involves gripping the male genitalia and ripping and tearing as a throw is made.

i) Shoulder Throw. By ducking inside the opponent – the opponent is ‘uprooted’ and thrown whilst being made to roll across the shoulder area.

j) Kneel and throw. The wrestler drops to his or her knees and rushes into the knee area of the opponent – causing an ‘uprooting’ action to occur.

An old Chinese martial arts proverb says, ‘When fist-fighting is combined with wrestling – its potency is enhanced!’

The art of wrestling is also known as the art of ‘dropping’ (跌 - Die) an opponent! Throwing an opponent is the sudden ability of ‘uprooting’ and ‘pushing’ an opponent (with tremendous force) into the ground or against an object in the environment! The force of the ‘drop’ and ‘impact’ is designed to render the opponent ‘unconscious’ and to ‘break ‘bones’ and ‘dislocate’ joints! A perfectly executed throw can ‘kill’ an opponent due to the collision of the skull with the ground (or some other object). However, as a throw might not cause substantial damage, the wrestler will rain down punches, kicks, as well as elbow and knee strikes - until unconsciousness or death occurs in the opponent! At the very least, the Wrestler seeks to subdue the opponent.

The underlying principle of wrestling involves the ‘uprooting’ of an opponent through the clever use of leverage and pivotal force. Acting with an expert swiftness, the wrestler carries out a unified attack upon the opponent by entering into his or her defensive zone, making physical contact with the opponent’s body, and apply massive but highly concise and directed force to just the right spot! This is the ‘pivot’ - usually comprised of a set of bones and joint – into which force is applied, and over which the opponent will be thrown! Any part of the opponent’s body can be used in theory as a ‘fulcrum’ through which a throw can be applied. Obviously, with ‘neck’ the vertebrae will be broken, and death or permanent paralysis will result. Furthermore, a throw involving the legs or waist as the pivot can also lead to the opponent ‘dropping’ upon their head and breaking their neck in a similar fashion!

There are many ways to throw an opponent:

a) Hooking the Foot. The foot acts as the primary fulcrum whilst a damaging hold is simultaneously applied to the knee or elbow.

b) Impacting the Back. The back area of the opponent is used as a pivot – whilst being struck with a force that lifts the opponent off their feet! The opponent hits the ground backwards!

c) Catching Leg Attack. The opponent is thrown after their kicking leg is caught and their supporting leg is hooked off the ground! A dislocating hold is applied to the captured knee area through twisting, smashing, dropping or rising, etc.

d) Hanging Attack: The feet and legs are impacted backwards into the air – behind the opponent – so that he or she must ‘hang’ over the body of the attacker with their hands supporting their weight by touching the ground!

e) Upper Arm Attack. Placing the fulcrum (with speed and power) between the upper arm and the body of the opponent will cause an ‘uprooting’ to occur.

f) Pull and Twist. By securing elbow (and the arm either side) a twisting action causes the opponent to easily roll over an applied fulcrum.

g) Blocked Leg Attack. When the opponent attempts to take a step – the wrestler ‘blocks’ or ‘jams’ their feet, lower or upper leg sections so that their leg stops moving whilst their momentum continues to move! The ‘blocked’ leg becomes the fulcrum over which the opponent falls.

h) Piercing the Groin. By placing an arm between the legs of the opponent directly adjacent to the groin area, one of the opponent’s legs is secured for uprooting, twisting or displacing. By placing the entire body into the groinal area the opponent may be lifted and thrown. A variant involves gripping the male genitalia and ripping and tearing as a throw is made.

i) Shoulder Throw. By ducking inside the opponent – the opponent is ‘uprooted’ and thrown whilst being made to roll across the shoulder area.

j) Kneel and throw. The wrestler drops to his or her knees and rushes into the knee area of the opponent – causing an ‘uprooting’ action to occur.

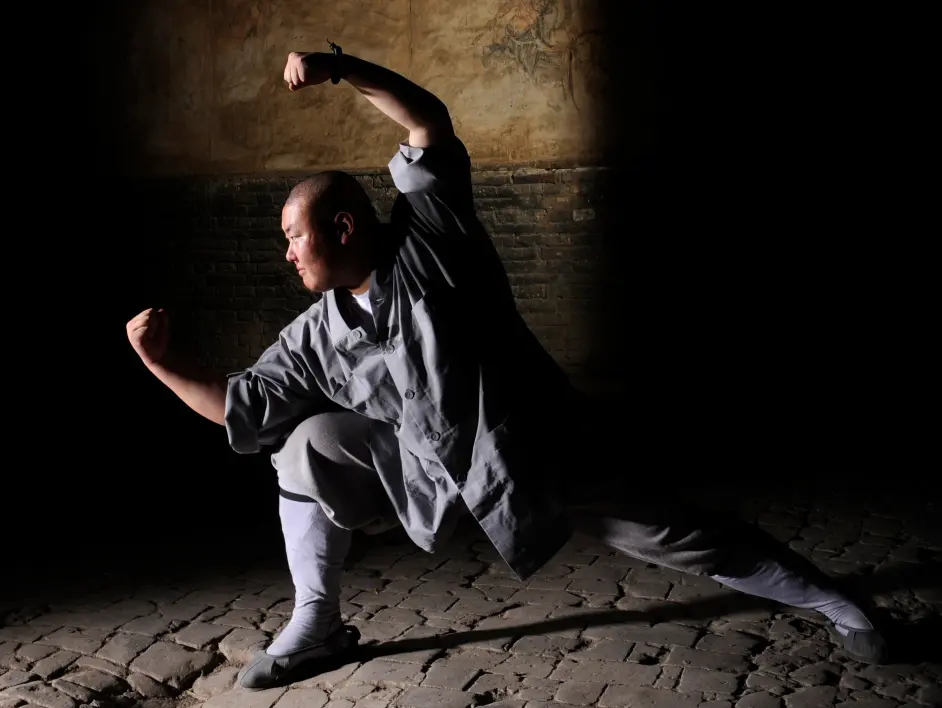

PART IV) Kick Law (踢法 - Ti Fa)

Kicking refers to the method of attacking and defending an opponent with the lower limbs. In ancient times, there was a clear way of defining the use of the legs when kicking. Unlike the development of modern ‘one on one’ combat-derived sport – where the individual fighters orientate all their blows toward a single opponent only ever stood to their front – the soldiers and martial artists of ancient China were taught to defend the four geographical directions with their legs! A front-kick was to the ‘front’, a side-keep was to the ‘side’, whilst a back-kick was to the ‘back’. The emphasis was on defending an area from multiple attackers coming from the South, North, West and East! To avoid knees being caught and seriously disabled and hurt by expert wrestlers and ‘Qinna’ experts, the old-style kicks within Chinese martial arts are performed without a knee-chamber (or transitionary ‘bent’ knee). Occasionally, armour was also worn that restricted leg movement.

Old Chinese proverbs state, ‘The hands and arms seal the door – whilst the feet and legs strike the attackers!’ and ‘The open hands hit three points – whilst the feet (and legs) strike seven points!’ The legs, in general, are longer than the arms and are much stronger! The feet can strike the head, torso, groin, knees and feet of the opponent with ease! Whilst standing and moving around using the legs, the legs and feet can be used tactically both for defence and offence!

When kicks are used properly, the feet and legs can break up an opponent’s attack and prevent any retaliatory response. Within the Ming Dynasty work of Qi Jiguang (戚继光) entitled ‘New Treatise on Military Efficiency’ (纪效新书 - Ji Xiao Xin Shu) - the ‘kicking’ skills of one ‘Li Ban Shan’ or ‘Mid-Level Li’ (李半山) from Shandong are mentioned! Master Li was very famous in Shandong for beating opponents and defeating enemies only through the use of his feet! This example justifies the saying, ‘Southern Fist – Northern Legs’ when describing a broad categorisation of expertise within traditional Chinese martial arts. In fact, both the Southern and Northern martial arts emphasis kicking – but due to the very different environments – the way of kicking can be very different.

Regardless of the type of kick, the technique must be both accurate and powerful whilst the legs should be flexible and nimble. With ‘internal’ (内 - Nei) kicking the power is ‘hidden’ (gained from aligning the bones and dropping the bodyweight – harvesting the rebounding force) and difficult to discern until the foot or leg ‘touches’ the opponent (as the ‘intention’ is subtle). It is the ‘quality’ of touch which facilitates the delivery of internal power (as all the qi energy channels are ‘open’, ‘unified’ and fully ‘functioning)! With ‘external’ (外 - Wai) kicking, the muscles, bones and joints must be well trained and toughened – whilst the kick itself is delivered with speed and power – generating massive impact force! When kicking, attention must be paid to the over-all position of the body! The hands and feet should be highly coordinated with the body whilst the eyes see everything! Kicking techniques include:

a) Front-Kick (heel and ball) - (upper, middle and lower level)

b) Side-Kick (heel and edge) - (upper, middle and lower level)

c) Back-Kick – (heel, edge and/or sole) - (upper, middle and lower level)

d) Groin - (heel, ball and top-flat) - (genitals, inner though and coccyx)

e) Knee strike- (heel, ball, edge and sole) - (stamping – low-level thrust)

f) Jumping - (heel, ball, edge and sole) - (any type of kick delivered with a ‘skip’)

g) Stepping - (heel, ball, edge and sole) - (stepping or stamping on opponent’s foot or other body part)

h) Shin - (striking with shin instead of foot)

i) Back-Heel - (striking to groin whilst opponent is stood behind kicker)

j) Knee lift - (striking any part of the opponent’s body – blocking any low and mid-level attack with a raised knee using upper and lower leg structure)

k) Block-Kicking - (using heel to ‘stop’ opponent moving forward and/or pushes opponent back)

l) Twisting - (crossing the legs and turning the body 180 degrees or more to gain momentum and confuse the opponent)

m) Round-Kicking - (delivered with both chambered and unchamber knee with devastating speed and power via flat of the top of the foot [large knuckle of the big toe] to head, torso and legs)

n) Axe-Kick - (leg is lifted higher than opponent’s head and brought down with force – striking with the heel)

Many of the oldest layers of Chinese martials forms possess only rudimentary kicks that were specialised and hidden in that style. Kicks were used sparingly – but when used they were used to devastating effect! Generally, if a kick, or set of kicks did not kill an opponent – these blows acted a prelude to the opponent being finished off with hand techniques or weaponry. Many of the flying kicks existed to knock opponents off horses or ponies (which the barbarians rode when attacking China). Other flying techniques are low-level ‘skips’ jumping over chained weaponry, or some other object aimed at the knees and shins. Feet could also be used to block, or parry unarmed or armed hand techniques. By aligning the pelvic-girdle, knees and ankle and heels – the leg structure may be kept rounded and yet robust so that it can absorb any incoming power without sustaining any serious damage.

Kicking refers to the method of attacking and defending an opponent with the lower limbs. In ancient times, there was a clear way of defining the use of the legs when kicking. Unlike the development of modern ‘one on one’ combat-derived sport – where the individual fighters orientate all their blows toward a single opponent only ever stood to their front – the soldiers and martial artists of ancient China were taught to defend the four geographical directions with their legs! A front-kick was to the ‘front’, a side-keep was to the ‘side’, whilst a back-kick was to the ‘back’. The emphasis was on defending an area from multiple attackers coming from the South, North, West and East! To avoid knees being caught and seriously disabled and hurt by expert wrestlers and ‘Qinna’ experts, the old-style kicks within Chinese martial arts are performed without a knee-chamber (or transitionary ‘bent’ knee). Occasionally, armour was also worn that restricted leg movement.

Old Chinese proverbs state, ‘The hands and arms seal the door – whilst the feet and legs strike the attackers!’ and ‘The open hands hit three points – whilst the feet (and legs) strike seven points!’ The legs, in general, are longer than the arms and are much stronger! The feet can strike the head, torso, groin, knees and feet of the opponent with ease! Whilst standing and moving around using the legs, the legs and feet can be used tactically both for defence and offence!

When kicks are used properly, the feet and legs can break up an opponent’s attack and prevent any retaliatory response. Within the Ming Dynasty work of Qi Jiguang (戚继光) entitled ‘New Treatise on Military Efficiency’ (纪效新书 - Ji Xiao Xin Shu) - the ‘kicking’ skills of one ‘Li Ban Shan’ or ‘Mid-Level Li’ (李半山) from Shandong are mentioned! Master Li was very famous in Shandong for beating opponents and defeating enemies only through the use of his feet! This example justifies the saying, ‘Southern Fist – Northern Legs’ when describing a broad categorisation of expertise within traditional Chinese martial arts. In fact, both the Southern and Northern martial arts emphasis kicking – but due to the very different environments – the way of kicking can be very different.

Regardless of the type of kick, the technique must be both accurate and powerful whilst the legs should be flexible and nimble. With ‘internal’ (内 - Nei) kicking the power is ‘hidden’ (gained from aligning the bones and dropping the bodyweight – harvesting the rebounding force) and difficult to discern until the foot or leg ‘touches’ the opponent (as the ‘intention’ is subtle). It is the ‘quality’ of touch which facilitates the delivery of internal power (as all the qi energy channels are ‘open’, ‘unified’ and fully ‘functioning)! With ‘external’ (外 - Wai) kicking, the muscles, bones and joints must be well trained and toughened – whilst the kick itself is delivered with speed and power – generating massive impact force! When kicking, attention must be paid to the over-all position of the body! The hands and feet should be highly coordinated with the body whilst the eyes see everything! Kicking techniques include:

a) Front-Kick (heel and ball) - (upper, middle and lower level)

b) Side-Kick (heel and edge) - (upper, middle and lower level)

c) Back-Kick – (heel, edge and/or sole) - (upper, middle and lower level)

d) Groin - (heel, ball and top-flat) - (genitals, inner though and coccyx)

e) Knee strike- (heel, ball, edge and sole) - (stamping – low-level thrust)

f) Jumping - (heel, ball, edge and sole) - (any type of kick delivered with a ‘skip’)

g) Stepping - (heel, ball, edge and sole) - (stepping or stamping on opponent’s foot or other body part)

h) Shin - (striking with shin instead of foot)

i) Back-Heel - (striking to groin whilst opponent is stood behind kicker)

j) Knee lift - (striking any part of the opponent’s body – blocking any low and mid-level attack with a raised knee using upper and lower leg structure)

k) Block-Kicking - (using heel to ‘stop’ opponent moving forward and/or pushes opponent back)

l) Twisting - (crossing the legs and turning the body 180 degrees or more to gain momentum and confuse the opponent)

m) Round-Kicking - (delivered with both chambered and unchamber knee with devastating speed and power via flat of the top of the foot [large knuckle of the big toe] to head, torso and legs)

n) Axe-Kick - (leg is lifted higher than opponent’s head and brought down with force – striking with the heel)

Many of the oldest layers of Chinese martials forms possess only rudimentary kicks that were specialised and hidden in that style. Kicks were used sparingly – but when used they were used to devastating effect! Generally, if a kick, or set of kicks did not kill an opponent – these blows acted a prelude to the opponent being finished off with hand techniques or weaponry. Many of the flying kicks existed to knock opponents off horses or ponies (which the barbarians rode when attacking China). Other flying techniques are low-level ‘skips’ jumping over chained weaponry, or some other object aimed at the knees and shins. Feet could also be used to block, or parry unarmed or armed hand techniques. By aligning the pelvic-girdle, knees and ankle and heels – the leg structure may be kept rounded and yet robust so that it can absorb any incoming power without sustaining any serious damage.

Chinese Language Source: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1711067371072439518&wfr=spider&for=pc

传统武术的四种基础技法

悦文天下

2021-09-16 22:03每日深度好文推荐官方帐号

「来源: |武研 ID:wwwsytj」

打、踢、摔、拿是中华民族在长期徒手相搏实践中,逐渐发展而成的具有代表性和民族性的技击法。此法充分发挥人体各部分能动性,以达到制敌取胜的目的。

武术四技周时已具维形。《公羊传》在叙述当时的手搏活动时,就有“绝其脱(dou)”的描写。脱即喉,“绝其应”就是擒拿中的锁喉法。武术四技形成于汉代,成熟于宋明。戚继光《纪效新书》中就有山东李半山之腿、鹰爪王之拿、千跌张之跌、张伯敬之打的记载。

一、打法

打,指徒手散打(彩图八)。打法,即徒手散打的技法。所谓技法,就是根据对方体能、技能、临场表现特点和薄弱环节等情况而采用的有利子发挥自身体能和技能、战胜对手的攻防原则。人具有高度智慧,对打时,双方打法变化莫测,故打法没有固定的套路。打法讲究战术,制敌取胜靠的也是战术。在散打中,只有采用相应的战术,才能达到制敌取胜的目的。战术的运用首先建立在了解人体各部位及薄弱部位的基础上。中国武术的“八打”法就是针对易于制服对手的经验之谈:

一打眉毛双眼(指眉弓和眼腈)

二打属上人中(指鼻与唇之间的人中穴)

三打穿腮耳门(指腮部和耳门)

四打背后骨缝(指肩胛骨外缘)

五打肋内脏腑(指两肋)

六打撩阴高骨(指耻骨)

七打鹤膝虎头(指膑骨)

八打破骨千金(臁骨)

中华武术的打法,充满了辩证法,其核心是一个“变”字。康戈武《中国武术实用大全》认为“变”有三种基本原则:

(一)临机应变。即临场对敌时,根据亲身感知到的对方技能和体能情况,修正事前制定的作战方案,采用符合实际的打法,为取胜奠定基础。

(二)以变应变。即随对手的变化而及时变化自己的打法,以便寻找战机,达到因机立胜的目的。

(三)以变引变。即《孙子兵法.虚实篇》“致人而不致于人”的战术,“即我有目的的主动变化,引动对手变换打法或招式,使我主动,对方被动,敌在被牵动的过程中,逐渐将对方引入我设下的阁套而受到制约。”

打法的战术还有“先发制人”和“后发制人”。“先发制人”指先发动进攻取得主动权,使敌方处于被动,进而制服对手。“后发制人”是先让对方发招进攻,我避其锐,等对方神泄体疲露出空隙时,再发招反攻。中华民族的性格含而不露,善于以柔克刚、以静待动和后发制人,面不像西方的拳击-开始就咄础逼人,连连出击。中华武术的打法很多,主要体现在虚实动静的运用方面,如虚实相生、实中有虚、虚中有实、虚而实之、实而虚之、避实就虚、避虚就实、以静待动、以动制静、舍己从人等等。

二、拿法

拿,即擒拿。是针对人体各部关节和穴道,拿其一部,制敌全身,使对方失去反抗能力的技术。

擒拿早在明代已自成体系,如《江南经略》介绍擒拿法有三十六拿和三十六解。今天,在各种形式的武术竞赛中,已不准使用其法,但擒拿法仍可用来自卫防身和捕贼擒犯。

擒拿法由擒拿和反擒拿两种技法组成。擒拿主要分为拿骨法、拿筋法、点穴法三类。

拿骨法:此法专拿对方骨关节和人体较小骨头,如锁骨、肋骨、指骨等处,通过扳折和拧错,造成对方剧疼、关节脱臼或骨骼断裂,达到制敌取胜的目的。拿骨法的主要招法有拿、挖、搬、扣、捏等。

拿筋法:用五指抓对方肌肉、筋脉、韧带,使与之相连的肌束,筋脉、韧带分离或严重错位,失去运动能力。拿筋法有十种:抓、捏、提、抗、挖、合、摘、卡、揪、顶。

点穴法:气血是人的生命之本,循行全身,永无静止。气血:一旦阻闭,人的运动便受制约,轻者失去运动能力,重者丧失生命。而点穴法正是抓拿对方紧要穴道,阻闭气血流通,以此影响对方肢体正常运动的技术。点穴法具有很大功效,被称为“擒拿之冠”。点穴法常用的穴位有厥阴、眉心、章山、合谷、曲池、气位、麻穴、痛穴、晕穴、哑穴等。

擒拿法技术性很强,要求快速准确、精通劲力、内外合-和随机应变。

擒拿的基本原则有四点:

(一)拿其一穴,控制-点。

(二)以巧取胜,以技制人。

(三)动中有静,静中有动。

(四)拿中有解,解中有拿。

有擒拿必有反擒拿。所谓反擒拿即当对方抓我某一部位时,我使用一定的技法将其破解。反擒拿的解法很多,主要分为二类:

(一)以拿破拿。对方拿我时,我还以拿法,使之被拿。

(二)以打破拿。用各种打法破其拿法,使之放弃拿法。

擒拿可以单练,也可以双人对练。

三、摔法

拳谚道:“拳加跤,艺更高。”

摔法也称摔跌法,摔跌法和摔跤虽然都以使对方身体失去平衡摔倒在地为目标,但摔跤摔倒对方即胜,而摔跌法摔倒对方以后,还打、踢,直到制服对手。

摔跌法的原理是运用受力平衡杠杆等力学原理,通过手、眼、身、脚的巧妙配合,破坏对方身体平衡使之跌倒,从而迅速掌握主动,击败对方。摔跌法讲究快速,-触即摔,一触即跌。

摔跌法很多,主要有以下几种:

勾脚跌:在上肢配合下,用勾脚摔倒对方。勾脚跌分锁臂勾脚跌和抄腿勾脚跌。

抢背跌:在倒地前滚时,用手法以摔倒击倒对方的跌法。

抄腿摔:当对方以脚踢我,我以抄腿而摔之的方法。常见的抄腿摔有抄腿拧摔、抄腿踹膝、抄腿勾踢等。

挂塌跌:以脚后跟挂其脚,以手前塌其背的跌法。要求挂与塌时向相反方向用力。

封臂摔:上封臂,下绊脚。

扳拧摔:扳肘拧臂使对方摔出的方法。

别腿摔:以步别住对方腿,使对方摔出的跌法。

穿裆跌:以手臂穿过对方档部再抱腿上抬,扛而摔之的跌法。

靠身跌:以肩背后靠,掷跌对方的方法。

跪膝跌:下绊上推的跌法。

-------------------

四、踢法

踢法指以下肢进行攻防的方法。古代对踢时出腿的形式都有明确的称法,腿之横出为骈(pion),平出为站(tie),横而里出为踩,扁出为扁踩。在技击中,踢法十分重要,有时甚至起关键作用。腿比上肢长,力量也比上肢强,上可踢头、胸,中可踢腹、腰,下能踢腿。技击时,腿法既可作为进攻也可作为防守之用。故拳谚道:“双手封死门,全凭腿打人”,“手打三分,腿踢七分”。踢法运用得当,能够有效地化解对方的攻击,打击对方。《纪效新书》介绍,山东李半天就以踢法高超著名于世。武林中,素有“南拳北腿”的说法。其实,南北武术都注重发挥腿踢的作用,只是由于南北环境不同,踢的方式方法不同而已。

踢法的技击性很强,从内而言,要有进攻意识,就外而言,发腿要迅速有力,收腿要灵活敏捷,踢时要注意全身各部位的配合,手、眼、身、步要高度协调。

武术的踢法有几十种:以弹、蹬、踹、点、铲、缠、拐、错、钩、踢为主,又有里合、外摆、后撩、倒踢、前扫、后扫、旋踢等,还可结合腾空跃跳做出飞脚、连环脚、摆莲、箭弹、蹬踢、侧踹以及各种转体踢法,如旋踢、旋风腿等。实战中,多种踢法并用,往往令对方挡不胜挡。

传统武术的四种基础技法

悦文天下

2021-09-16 22:03每日深度好文推荐官方帐号

「来源: |武研 ID:wwwsytj」

打、踢、摔、拿是中华民族在长期徒手相搏实践中,逐渐发展而成的具有代表性和民族性的技击法。此法充分发挥人体各部分能动性,以达到制敌取胜的目的。

武术四技周时已具维形。《公羊传》在叙述当时的手搏活动时,就有“绝其脱(dou)”的描写。脱即喉,“绝其应”就是擒拿中的锁喉法。武术四技形成于汉代,成熟于宋明。戚继光《纪效新书》中就有山东李半山之腿、鹰爪王之拿、千跌张之跌、张伯敬之打的记载。

一、打法

打,指徒手散打(彩图八)。打法,即徒手散打的技法。所谓技法,就是根据对方体能、技能、临场表现特点和薄弱环节等情况而采用的有利子发挥自身体能和技能、战胜对手的攻防原则。人具有高度智慧,对打时,双方打法变化莫测,故打法没有固定的套路。打法讲究战术,制敌取胜靠的也是战术。在散打中,只有采用相应的战术,才能达到制敌取胜的目的。战术的运用首先建立在了解人体各部位及薄弱部位的基础上。中国武术的“八打”法就是针对易于制服对手的经验之谈:

一打眉毛双眼(指眉弓和眼腈)

二打属上人中(指鼻与唇之间的人中穴)

三打穿腮耳门(指腮部和耳门)

四打背后骨缝(指肩胛骨外缘)

五打肋内脏腑(指两肋)

六打撩阴高骨(指耻骨)

七打鹤膝虎头(指膑骨)

八打破骨千金(臁骨)

中华武术的打法,充满了辩证法,其核心是一个“变”字。康戈武《中国武术实用大全》认为“变”有三种基本原则:

(一)临机应变。即临场对敌时,根据亲身感知到的对方技能和体能情况,修正事前制定的作战方案,采用符合实际的打法,为取胜奠定基础。

(二)以变应变。即随对手的变化而及时变化自己的打法,以便寻找战机,达到因机立胜的目的。

(三)以变引变。即《孙子兵法.虚实篇》“致人而不致于人”的战术,“即我有目的的主动变化,引动对手变换打法或招式,使我主动,对方被动,敌在被牵动的过程中,逐渐将对方引入我设下的阁套而受到制约。”

打法的战术还有“先发制人”和“后发制人”。“先发制人”指先发动进攻取得主动权,使敌方处于被动,进而制服对手。“后发制人”是先让对方发招进攻,我避其锐,等对方神泄体疲露出空隙时,再发招反攻。中华民族的性格含而不露,善于以柔克刚、以静待动和后发制人,面不像西方的拳击-开始就咄础逼人,连连出击。中华武术的打法很多,主要体现在虚实动静的运用方面,如虚实相生、实中有虚、虚中有实、虚而实之、实而虚之、避实就虚、避虚就实、以静待动、以动制静、舍己从人等等。

二、拿法

拿,即擒拿。是针对人体各部关节和穴道,拿其一部,制敌全身,使对方失去反抗能力的技术。

擒拿早在明代已自成体系,如《江南经略》介绍擒拿法有三十六拿和三十六解。今天,在各种形式的武术竞赛中,已不准使用其法,但擒拿法仍可用来自卫防身和捕贼擒犯。

擒拿法由擒拿和反擒拿两种技法组成。擒拿主要分为拿骨法、拿筋法、点穴法三类。

拿骨法:此法专拿对方骨关节和人体较小骨头,如锁骨、肋骨、指骨等处,通过扳折和拧错,造成对方剧疼、关节脱臼或骨骼断裂,达到制敌取胜的目的。拿骨法的主要招法有拿、挖、搬、扣、捏等。

拿筋法:用五指抓对方肌肉、筋脉、韧带,使与之相连的肌束,筋脉、韧带分离或严重错位,失去运动能力。拿筋法有十种:抓、捏、提、抗、挖、合、摘、卡、揪、顶。

点穴法:气血是人的生命之本,循行全身,永无静止。气血:一旦阻闭,人的运动便受制约,轻者失去运动能力,重者丧失生命。而点穴法正是抓拿对方紧要穴道,阻闭气血流通,以此影响对方肢体正常运动的技术。点穴法具有很大功效,被称为“擒拿之冠”。点穴法常用的穴位有厥阴、眉心、章山、合谷、曲池、气位、麻穴、痛穴、晕穴、哑穴等。

擒拿法技术性很强,要求快速准确、精通劲力、内外合-和随机应变。

擒拿的基本原则有四点:

(一)拿其一穴,控制-点。

(二)以巧取胜,以技制人。

(三)动中有静,静中有动。

(四)拿中有解,解中有拿。

有擒拿必有反擒拿。所谓反擒拿即当对方抓我某一部位时,我使用一定的技法将其破解。反擒拿的解法很多,主要分为二类:

(一)以拿破拿。对方拿我时,我还以拿法,使之被拿。

(二)以打破拿。用各种打法破其拿法,使之放弃拿法。

擒拿可以单练,也可以双人对练。

三、摔法

拳谚道:“拳加跤,艺更高。”

摔法也称摔跌法,摔跌法和摔跤虽然都以使对方身体失去平衡摔倒在地为目标,但摔跤摔倒对方即胜,而摔跌法摔倒对方以后,还打、踢,直到制服对手。

摔跌法的原理是运用受力平衡杠杆等力学原理,通过手、眼、身、脚的巧妙配合,破坏对方身体平衡使之跌倒,从而迅速掌握主动,击败对方。摔跌法讲究快速,-触即摔,一触即跌。

摔跌法很多,主要有以下几种:

勾脚跌:在上肢配合下,用勾脚摔倒对方。勾脚跌分锁臂勾脚跌和抄腿勾脚跌。

抢背跌:在倒地前滚时,用手法以摔倒击倒对方的跌法。

抄腿摔:当对方以脚踢我,我以抄腿而摔之的方法。常见的抄腿摔有抄腿拧摔、抄腿踹膝、抄腿勾踢等。

挂塌跌:以脚后跟挂其脚,以手前塌其背的跌法。要求挂与塌时向相反方向用力。

封臂摔:上封臂,下绊脚。

扳拧摔:扳肘拧臂使对方摔出的方法。

别腿摔:以步别住对方腿,使对方摔出的跌法。

穿裆跌:以手臂穿过对方档部再抱腿上抬,扛而摔之的跌法。

靠身跌:以肩背后靠,掷跌对方的方法。

跪膝跌:下绊上推的跌法。

-------------------

四、踢法

踢法指以下肢进行攻防的方法。古代对踢时出腿的形式都有明确的称法,腿之横出为骈(pion),平出为站(tie),横而里出为踩,扁出为扁踩。在技击中,踢法十分重要,有时甚至起关键作用。腿比上肢长,力量也比上肢强,上可踢头、胸,中可踢腹、腰,下能踢腿。技击时,腿法既可作为进攻也可作为防守之用。故拳谚道:“双手封死门,全凭腿打人”,“手打三分,腿踢七分”。踢法运用得当,能够有效地化解对方的攻击,打击对方。《纪效新书》介绍,山东李半天就以踢法高超著名于世。武林中,素有“南拳北腿”的说法。其实,南北武术都注重发挥腿踢的作用,只是由于南北环境不同,踢的方式方法不同而已。

踢法的技击性很强,从内而言,要有进攻意识,就外而言,发腿要迅速有力,收腿要灵活敏捷,踢时要注意全身各部位的配合,手、眼、身、步要高度协调。

武术的踢法有几十种:以弹、蹬、踹、点、铲、缠、拐、错、钩、踢为主,又有里合、外摆、后撩、倒踢、前扫、后扫、旋踢等,还可结合腾空跃跳做出飞脚、连环脚、摆莲、箭弹、蹬踢、侧踹以及各种转体踢法,如旋踢、旋风腿等。实战中,多种踢法并用,往往令对方挡不胜挡。