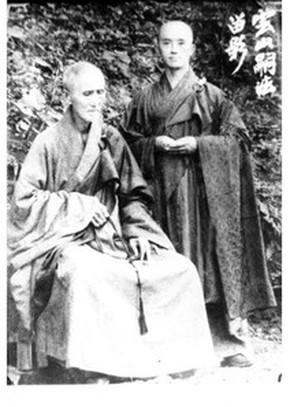

Master Xu Yun and his Martial Arts Ch’an Disciples

By Adrian Chan-Wyles (PhD)

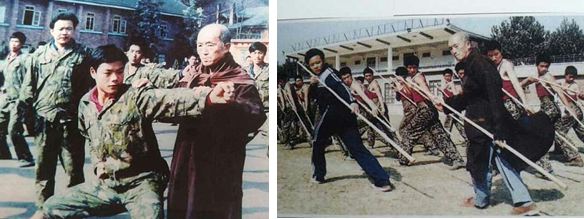

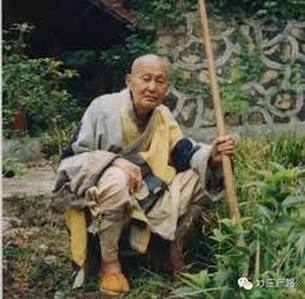

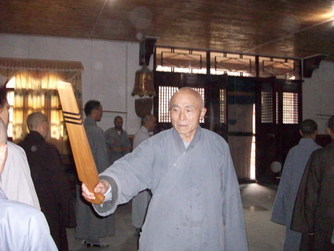

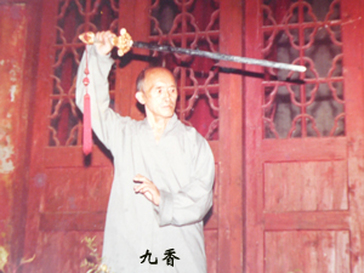

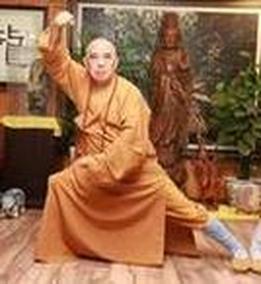

Master Xu Yun had at least three (and probably more) disciples who were also martial artists and linked to the Shaolin Temple tradition. This is an important point that should serve to inspire any and all modern martial artists who train to develop the mind and body, and pursue peace, tranquillity, and wisdom throughout society. The practice of Chinese martial arts is a legitimate and genuine aspect of the practice of Chinese Ch’an Buddhism. The three ordained Ch’an Buddhist monks that also practised martial arts, whilst simultaneously receiving Ch’an instruction from Master Xu Yun are:

Practising martial arts in China is an ancient pursuit always premised upon the noble concept of communal self-defence. The practice of individual martial movements, and groups of martial movements derived from the mimicking of animals observed (thousands of years ago) when fighting either for survival, competing for food, territorial domination, or mating rights. Each type of animal, being perfectly adapted to its environment, deployed a specific use of its body and its natural weaponry, such as teeth, claws, horns, bone-structure, limbs, and movement within a particular environment. It was also observed that animals when fighting adopted unique body postures and positioning, whilst employing an aggressive mind-set calculated to be hyper-aware during combative situations.

Early Chinese society developed shamanistic beliefs thousands of years ago, and part of this tradition involved shamans – or holy men and women – who sometimes dressed as animals (often wearing head-dresses of antlers) – perform highly ritualised dances whilst carrying staffs or clubs, and making elaborate martial movements based upon fighting animals. From this, it can be seen that from its inception, Chinese martial arts (which pre-date Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism) began as a primarily ‘spiritual’ act designed to link humanity to nature and nature spirits. In early Chinese combat – fighting was quite literally an act of spiritual worship designed to bring ‘wholeness’ or ‘oneness’ between the quite often vulnerable groups of humanity and nature. Perhaps with this close ritualistic association with animals, early human societies believed that they were taking control of nature and in a sense protecting itself from its danger, unpredictability, and excesses.

This may well have been a pattern of development observable in all early human cultural groupings, but due to the longevity and stability of Chinese culture, it is an attribute of human adaptation that has survived into modern times in China. In fact the adherents of Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism – whether they actively participate or not – view the practice of martial arts as not only compatible, but also a crucial vehicle for psychological and physical development, longevity and well-being. In this practice there is no contradiction between the establishing and preserving of peace in the outer environment, and the permanent establishing of inner peace in the mind and body. Chinese martial arts, regardless of which tradition they are a part of, are not ‘violent’, but rather its exact opposite, and the definite ‘end’ of all violence (in the mind, body and environment). This is why Master Xu Yun never decried martial arts practice (such as that developed in the Shaolin Temple), but accepted it as a legitimate aspect of the Chinese Buddhist practice. The point is that there are thousands of Ch’an Buddhist temples in China, many of which either officially or unofficially pursue a martial curriculum. This is true even if the Ch’an Temple has no direct connection with the Shaolin Temple or its specially developed martial culture. Of course, as the Shaolin Temple is believed to be the birthplace of Ch’an Buddhism in China, it can be truthfully said that ALL other Ch’an temples are in that manner, inherently connected to it.

©opyright: Adrian Chan-Wyles (ShiDaDao) 2016. |