Shaolin Culture is Steeped in Ch’an PracticeOriginal Chinese

Language Article: By Fei Hong Huang (飞鸿黄)

(Translated by Adrian Chan-Wyles PhD) Translator’s Note: This is an English language translation of

an original Chinese language text. This

is part 3 of a 3 part series in the Chinese language regarding the integration

and practice of Shaolin martial and Ch’an culture. This text is significant as it confirms that

the Shaolin Temple has historically preferred (and emphasised) the Caodong Sect

of Ch’an Buddhism. The Shaolin Temple

was founded in 495 CE by the Northern Wei Dynasty emperor – Xiaowen – with the

first Abbot being the Indian Buddhist monk Buddhabhadra. He had a number of Chinese students who were

martial art practitioners before they entered the temple – and through the

mental and physical discipline associated with Ch’an training – their mastery

of martial arts was enhanced. Master

Chan Tin Sang (1924-1993) of the Ch’an Dao Martial Arts Lineage, and the Great

Ch’an Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) both preferred the Caodong transmission – even

though in the case of Xu Yun – he had inherited all Five Schools of Ch’an. Within the history of the Hakka Ch’an Dao

School, many of the ancestral practitioners as young men, spent time as

ordained Buddhist monks within various Ch’an temples, including (it is

rumoured) the Shaolin Temple in Fujian province. It is interesting to note that when Ch’an was

transmitted to Japan (as Zen), it was the Linji (Rinzai) tradition that became

associated with martial practice – with the Caodong (Soto) tradition being

relegated to the practice of farmers.

This is the inversion of the reality in China – where the Linji (Rinzai)

is not associated with the martial arts of the Shaolin Temple – although, of

course, all Five Ch’an Schools reveal exactly the same empty mind ground, and

many martial arts practitioners practiced Ch’an from any and all of the

lineages in China.

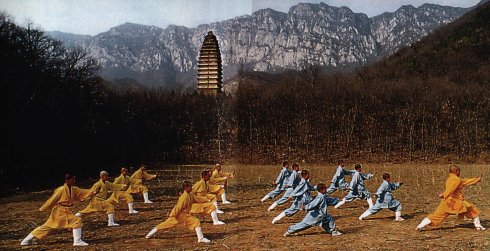

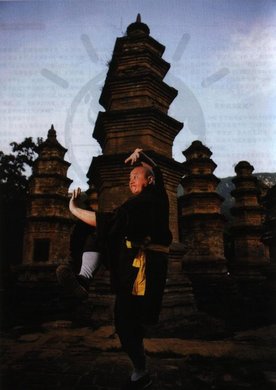

ACW 17.7.15 A defining characteristic of Shaolin culture is that ‘Ch’an

and Martial Practice are One’.

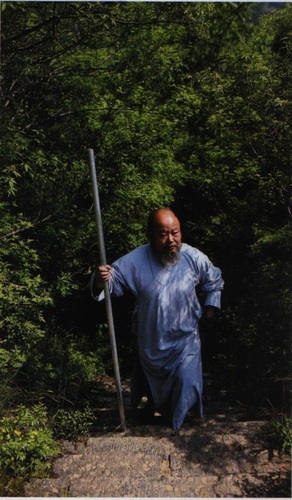

It is well known that the culture of the Shaolin Temple is entirely premised upon the practice of the Chinese Ch'an Buddhist tradition. In fact, the practice of Chinese Ch'an Buddhism is the single most important aspect of the Shaolin tradition. This can be seen even in the movies that feature the Shaolin Temple, as many depict martial mastery as being the natural consequence of Ch'an meditational practice. Records of the early history of Shaolin suggests that the

martial tradition of physical fitness began with the temple’s first abbot –

Buddhabhadra – who ‘skilfully combined martial movement with seated

meditation’.

Toward the end of the Sui Dynasty, the martial monks of the

Shaolin Temple assisted Li Shi Min and (his military forces) sweep to a final

victory – in this achievement the Shaolin tradition played a significant

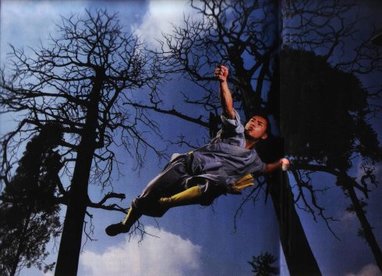

role. The physical movements and ‘forms’

of the genuine Shaolin fighting system evolved into a very effective means of

self-development and self-defence – and eventually the Caodong lineage of Ch’an

became the preferred lineage of Buddhism in the temple. This unique combination ensured that the Shaolin

tradition became known as a ‘temple that specialised in martial

self-cultivation’ to a very high degree.

To this end, the benefits of the Caodong lineage of Ch’an cannot be

underestimated as an important component of martial mastery.

After much experimentation and deliberation, the distinctive

Shaolin martial culture was established that emphasised that ‘Ch’an and Martial

Practice are One’. This careful process

of assessment, clarification, and refinement, enabled the correct and true

Shaolin path to be established.

Prior to the Qing Dynasty, however, it is understood that the emphasis in the Shaolin Temple at that time was on training monks in advanced martial technique. At one time, General Yu Da You (1503–1579) – who was famous for resisting invasions of China - visited the Shaolin Temple and observed a number of monks practicing stick-fighting. Yu Da You was of the opinion that the techniques were overly elaborate and far too ritualised to be of any use in actual combat. To rectify this problem, the Abbot of the Shaolin Temple sent two monks to accompany Yu Da You to gain practical experience of fighting at the battle-front. In this way these two monks learned what a practical martial art was like when used in battle. Afterwards, these two monks then brought back their knowledge and experience to the Shaolin Temple – which was added to the Shaolin tradition – and became known as the Law of Stick-fighting. Stick-fighting – and it’s not so obvious use in combat –

developed relatively late in Shaolin history, but once developed, it has been

generally praised for its sophistication and combat-usefulness. Shaolin martial arts, as they are known

today, consolidated during the Qing Dynasty, and although the Shaolin tradition

is very old, it is from this time period that the arts known today as ‘Shaolin’

appear to have developed.

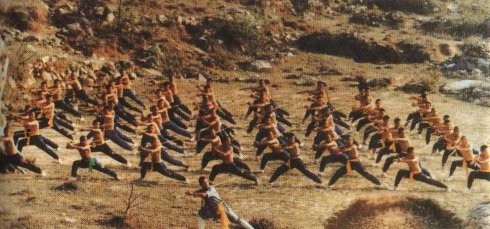

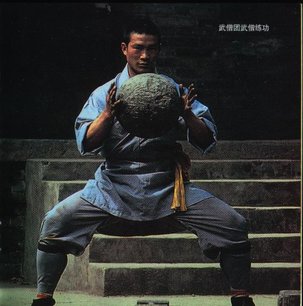

Many people view Shaolin Fist as a prime example of

traditional Shaolin martial arts, with such well-known techniques as:

a) Fighting with the Fist like an Ox Crouching on the Ground b) Come and Go in a Single, Unified Movement c) Like Singing without a Song – Like a Straight-line that is Not Linear – Roll-out and Roll-in d) Stand-up and Look Tall – Hide the Body whilst Standing – Crouch-down and Looking Small – Exhibit the Body whilst Crouching Obviously the Shaolin martial tradition is premised on

practical combative martial art at its core, that emphasis the unity of

offensive and defensive technique, the integration of forward and back movement,

and the integration of hard and soft energy production. This reveals a direct and unpretentious

theory of developmental understanding, premised upon refinement through dialectical

philosophy. The extent of the excellence

of this complete Shaolin tradition can be seen in the fact that its martial

arts has spread all over the country (and the world).

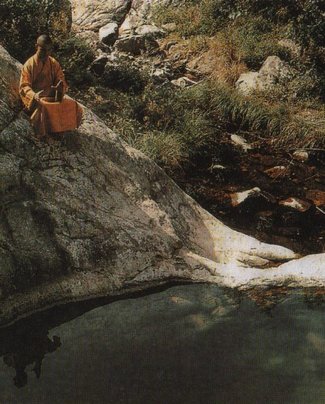

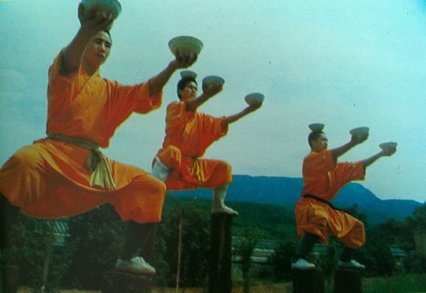

‘Ch’an and Martial Practice are One’ – this is a profound

concept that has become enriched through specialisation. This is how the Shaolin Temple explains the

various levels of martial attainment:

1) The practice of ‘forms’. 2) The ‘Spirit and the Fist are One’ – this is the integration of ‘form’ and ‘void’. 3) The ‘Ch’an and Martial Practice are One’ – this is the integration of martial practice and Ch’an – or body with mind – a development that is driven by the generation of profound wisdom produced by a ‘concentrated’ and ‘still’ mind. The highest level of attainment of Shaolin martial culture is nothing less than the highest attainment of ‘prajna wisdom’ through the Ch’an meditative method. This gives a very profound understanding of movement (and stillness) so that the correct way is always perceived and understood. ©opyright: Adrian Chan-Wyles (ShiDaDao) 2015. Original Chinese Language Source Article http://blog.sina.cn/dpool/blog/s/blog_637f80dd01010brd.html 少林合是禅栖地(三) 少林寺“禅武合一”的特色 大谈少林寺的禅宗,是为了引出少林寺独有的特色文化产品,也是少林电影中真正的主角——少林武术。 从有关少林寺的史料中,我们会发现,少林僧人从来就有健体强身的传统。据说跋陀的弟子僧稠就身怀绝技,堪称“少林武僧第一人”。少林寺能够在隋末乱世中协助李世民作战并取得最终胜利,这一传统发挥了巨大的作用。但少林武术真正形成体系,并导致“寺以武显”的效果,应该说还得益于禅宗——曹洞宗——所提供的理论基础。 经过研究与推敲,少林寺“禅武合一”的理念最终被确立了起来,练习武术成为了僧人们修行的正途。 据了解,清代之前的少林武术,因为要适应于当时的僧兵制度,其内容主要是军事实战技术。著名的抗倭将领俞大猷便曾经到少林寺指点过僧人练棍,对于当时出现的花巧倾向进行过纠偏。少林寺当时派了两位武僧跟随他去了作战前线,在战争中学习战争,然后又将所学带回寺院,使少林棍法冠绝天下。 后世为人称道的少林拳晚于少林棍发展,因为拳术在军事作战中的作用并不明显。至于少林武术在形态、功法、技法上真正形成完整的体系和独到的风格,应该是在清代。 人们多以少林拳术为例说明传统少林武术的特点,如“拳打卧牛之地”、“来去一条线”、“似曲非曲、似直非直、滚出滚入”、“起望高、缩身而起,落望低,展身而落”等等。显然以实战技击为核心,强调攻防合一、进退一体、刚柔相济、朴实无华的辩证哲学理念。拳为诸艺之本,由此确可窥一斑而知全豹。 [转载]少林合是禅栖地(三) “禅武合一”理念在发展中也得到了充实与规范,寺方如今的解释是:少林武术修炼的第一个层次是练形;第二个层次是“神拳合一”,即化有形为无形;第三个层次才是“禅武合一”,即由武入禅,由定生慧,将少林武术视为在禅定状态下用“般若慧”观照下的人体运动方式 |