|

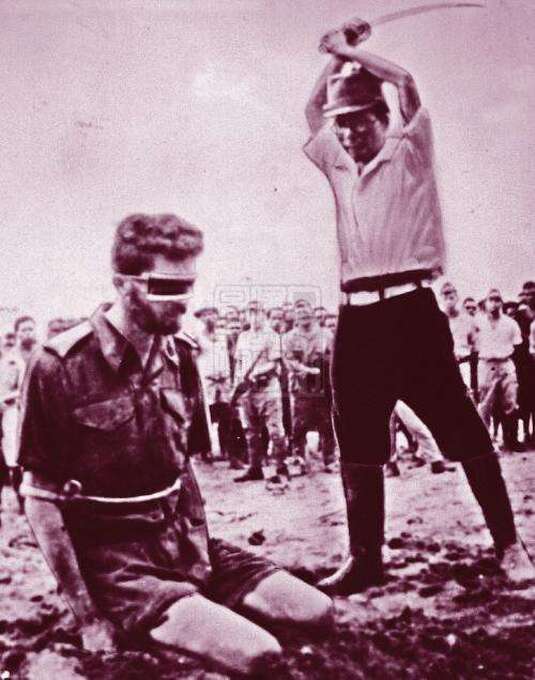

Within the Movie ‘Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence’ a Japanese POW Camp Commandant decides that the prison population of European (military) inmates are ‘spiritually lazy’. When being beaten or made to stand for hours in the sun had not altered this situation, the Japanese Officer decided that the Camp population would undergo the Shinto ritual of ‘Misogi’ (禊) – in this instance – involving a 24-hour fast-period of no eating or drinking. This is despite the daily ration being intolerably low to start with. Most prisoners – even the stronger men – were on the brink of starvation. The Japanese Officer (Captain Yanoi) – by further depleting the starvation rations - would also adhere to this ritual of ‘fasting’ whilst traditionally dressed - and sat in meditation in the Camp ‘Dojo’. This is the pristine training hall used by the Japanese Officers for martial arts and spiritual practice (a mixture of Buddhist and Shinto spiritual traditions). Similarly, in the book ‘Empire of the Sun’ written by JG Ballard – the (civilian) POW Camp (Assistant) Commandant (Sergeant Nagata) occasionally orders Chinese vagrants (often women and girls) to be ‘beaten to death’ by Japanese soldiers wielding wooden clubs. The actual 'Commandant' - Hyashi - was in fact a 'civilian' and a careerist diplomat who tended to only interfere in Camp daily activities if absolutely necessary. Obviously, Hyashi never interfered in Nagata's brutality. These starving Chinese people sit patiently outside the POW Camp waiting to see if they will be allowed in to receive a portion of the already meagre rations. The women and girls are often raped by the Japanese guards before the Camp populace of British people are assembled to watch the unfolding ritual of ‘despatch’. Sergeant Nagata believes the British POWs are ‘spiritually lazy’ and seeks to stimulate their individual (and collective) ‘ki’ (氣) flow. This ‘life force’ not only flows through each individual body – but also through the entire Camp. As Sergeant Nagata believes the Chinese people to be an ‘inferior race’ – their brutal murder (achieved through a demonstration of ‘Japanese’ manly vigour) – will ‘release’ the ‘ki’ from their (broken) bodies and supplement that available throughout the Camp. The two primary Shinto rituals on display in both of the above examples are: 禊 (Misogi) – Purification (Cleansing) of the inside and outside of the mind and body. 祓 (Harae) – Purification (Exorcism) of corruption out of the interior of the mind and body. As this ‘Kanji’ is in fact comprised of ‘Chinese’ ideograms, I can read these characters and give some type of explanation as to what these rituals are supposed to represent – at least in a historical context. I say this as the rubric of Japanese ‘spiritual’ fascism distorted (for decades) rituals and practices that would normally not have been so severe or murderously brutal. Bear in mind that within ten-years of WWII being over – Western students of Judo, Kendo and Karate-Do were avidly volunteering to undergo these rituals – albeit in a non-war setting. Nevertheless, the rituals that the Imperial Japanese used to torture and murder millions of Western and Asian people – are today routinely considered part and parcel of a legitimate Japanese martial arts practice. On the face of it, this is an extraordinary rehabilitation. As Chinese ideograms, these ‘Kanji’ characters can be read as follows: a) 禊 (xi4) is comprised of an upper and lower particle: Upper Particle = 气 (qi4) – refers to ‘energy’, ‘breath’ and ‘vital force’ Lower Particle = 米 (mi3) – denotes husked ‘rice’ that needs to be ‘cooked’ (transformed) in water Therefore, 禊 (xi4) suggests that the process of cooking rice in a cauldron (by lighting a fire underneath and boiling the water) not only produces nutritious food (which sustains all physical life) but also generates ‘steam’ as a useful and yet crucial by-product. This steam - through the (hidden) ‘pressure’ created - ‘lifts’ the lid of the cauldron with an effortless ease. It is this ‘unseen’ influence of a physical process that drives this concept. b) 祓 (fu4) is comprised of of a left and a right particle: Left Particle = 礻(shi4) is a contraction of ‘示’ (which denotes an ‘altar’ and the ‘rituals’ associated with it) – and refers to structured acts of ‘instruction’, that require ‘attention’ and possess great ‘importance’. Lower Particle = 犮 (ba2) denotes a ‘dog’ (犬 – quan3) that is ‘running’ (丿- pie3). The implied meaning is to perform a dramatic task with the appropriate amount of effort and required energy. This suggests that a religious ritual must be correctly performed (as if in a temple or at an altar) in the physical world - that opens a connecting door-way to the spiritual world. Once this channel has been correctly opened – the influence of the spiritual world is then allowed to positively flow (unseen) into the material world – thus influencing temporal events. Correct (disciplined) and timely action in the physical world is the basis of this concept. Success is defined as achieving an exact ritualistic replication that does not deviation from the accepted norm – as ‘deviation’ of any sort is tantamount to ‘ill-discipline’. Conclusion Armed with this knowledge, it can be suggested that the Japanese concept of ‘禊’ (Misogi) refers to arduous physical activity that requires ‘sweating’. Through hard and continuous labour – a definite and positive metamorphosis is produced in the material world – that possesses definite (but ‘hidden’) implications for the inner world (almost as a side effect). By way of comparison, ‘祓’ (Harae) refers to a metaphysical ritual that although partly physical in its ritualistic content, remains nevertheless ‘metaphysical’ in nature and intent. This is because ‘祓’ (Harae) constitutes a ‘purifying’ spell achieved through words, actions, and a specific and certain state of mind.

0 Comments

The Island known as ‘Okinawa’ lies off of the South-West coast of Japan - forming part of the Ryukyu Island Chain - and is expressed in Japanese (Kanji) ideograms as ‘沖縄’. This name may be deconstructed as follows: a) oki (沖) = expanse of open water b) nawa (縄)= rope or thread The name appears to be a direct description of the numerous islands that comprise ‘Okinawa’ – which are themselves a substantial (Southern) part of the larger Ryukyu Island Chain. Perhaps the geographical placement and general shape of the islands was seen from high mountain-tops, surveyed in passing ships and/or observed from upon high by those who flew in the ‘Battle Kites’ known to exist within medieval Japan. Whatever the case, the Okinawa Island Chain is said to resemble a meandering rope lying across the surface of the water. I have read that this area first became known to China under the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) – but was not formally recognised by the Imperial Court until the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). This is when diplomatic and cultural contact with the King (of what was then termed the 'Liu Qiu' [琉球] Islands) was established - known today by the Japanese transliteration of 'Ryukyu'. 琉 (liu2) = sparkling-stone, jade, mining-stone (from previously uncultivated land), precious-stone, arriving, and breaking through (to a place far away - and situated on the fringes of the known world) 球 (qui2) = beautiful-jade, polished-jade, refined-jade, jade percussion instrument, earth, ball, and pearl. The Chinese Mariners must have been taken with the beauty of the Ryukyu Islands - as the term '玉' (yu4) – or ‘jade’ - appears as the dominant left-hand particle of both ideograms forming the name ‘Liu Qiu’. From the Tang Dynasty onwards, the Liu Qiu Islands were considered a distant (but important) part of the Tributary System of Imperial China. In return for a continuous show of annual respect (usually in the form of expensive gifts and/or elements of trade, etc) China shared her extensive culture. It was not until 1872 CE, however, that Imperial Japan took decisive action to annex all of the ‘Ryukyu’ Islands – and it was around this time that the term ‘Okinawa’ was developed to describe the Southern two-thirds of the Ryukyu Island Chain – now a ‘Prefecture’ of Japan. This history explains why the ideograms for ‘Okinawa’ are written in (Japanese) ‘Kanji’ - and are not obviously ‘Chinese’ in structure (as is the far older name of ‘Liu Qiu’). Is it possible to ‘reverse-engineer’ the Kanji ideograms associated with the name ‘Okinawa’ (沖縄) and work backwards as it were – to the original Chinese ideograms? The answer is ‘yes’ – as such an exercise might well shed some more light on the meaning of the name itself. Japanese - 縄 (nawa) = Chinese – ‘繩’ (sheng2) When adjusted in this manner - the Japanese name of ‘Okinawa’ (沖縄) is rendered into the Chinese language as ‘Chongsheng’ (沖繩). Whereas the first ‘Kanji’ ideogram of ‘沖’ (oki) remains identical with its Chinese counterpart of ‘沖’ (chong) - the second ‘Kanji’ ideogram (縄 - nawa) undergoes a substantial modification (繩 - sheng). From this improved data a more precise definition of the name ‘Okinawa’ can be ascertained through the assessment of the Chinese ideograms that serve as the foundation of the Kanji ideograms – working from the assumption that this meaning is still culturally implied through the use of ‘Kanji’ in Japan – even if such a meaning is not readily observable within the structure of the ‘Kanji’ ideograms themselves. 沖 (chong1) is comprised of a left and a right particle: Left-Particle = ‘氵’ which is a contraction of ‘水’ (shui3) – meaning water, river, flood, expanse of water, and liquid, etc. Right-Particle = ‘中’ (zhong1) refers to the concept of something being ‘central’, in the ‘middle’, or being perfectly ‘balanced’. It can also refer to an ‘arrow’ hitting the ‘centre’ with a perfect ease. Therefore, the use of 沖 (chong1) in this context - probably refers to an object that centrally exists within a body of water. 繩 (sheng2) is comprised of a left and right particle. Left-Particle = ‘糹’ which is a contraction of ‘糸’ (mi4) – meaning something that resembles a ‘silken thread’, a ‘thin’ and ‘flexible’ cord, a ‘rope’ or ‘string’, etc. This may also refer to the act of ‘weaving’ or to an object (like a rope, string, or strand) which is ‘woven’ into existence – perhaps implying a ‘cohesion’ attained through an ‘inter-locking’ agency, etc. Right-Particle = ‘黽’ (meng3) – this was originally written as a depiction of a type of frog – but evolved to be used generally to describe the act of ‘striving’, ‘endeavouring’, or ‘working hard’ (nin3). However, I am of the opinion that more practical attributes are at work in this instance. An old (but simplified) version of this ideogram is ‘黾’ – which demonstrates a clarification of what used to be a ‘frog’: This explains why there is said to be an ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ element to this particle: Upper-Element = ‘口’ (kou3) – signifies an ‘open mouth’, ‘entrance’, ‘mouth of a river’, and ‘port’. This can also denote a ‘boundary’ and a ‘hole’ or ‘indent’. This used to represent the head of a frog. Lower-Element = ‘电’ (dian4) – denotes ‘forked-lightning’, ‘energy’ and ‘electricity’, etc. Although evolving from the body of a frog – this element conveys not only the overt power of lightning – but perhaps retains something of the ‘shape’ of forked lightning in its usage as a noun. Perhaps 繩 (sheng2) is a descriptive term used to describe a port that allows entry to a string of islands which seem to take the shape of a rope that geographically unfurls - like forked lightning traversing the sky. Conclusion The term ‘Chongsheng’ (沖繩) – or ‘Okinawa’ - probably refers to a string of islands (and ports) which exist within a broad expanse of open sea - like a rope floating upon the surface of the water (the shape of which resembles that of forked-lightning). This place may be difficult to reach – and the people encountered may be very hard working. It is highly likely that these islands seem to float like a frog on the surface of the water – hence the selection of these ideograms. Of course, the post-1872 Japanese Authorities chose to use the Kanji ideograms of ‘沖縄’ to convey the concept and meaning of the name ‘Oki-Nawa’. In Chinese language texts, I do not see Okinawa referred to as an isolated unit of geographical description. This is because Chinese literature refers to the entire Chain of Islands by the far older and more traditional name of 'Liu Qiu' (琉球) – which was politically acknowledged through ancient diplomatic exchange. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the post-1872 Japanese Authorities did not abolish this Chinese name – but borrowed it – simply transliterating it into the now well-known ‘Ryukyu’ Islands. Okinawa is only around two-thirds of the Southern-Central area of the Ryukyu Islands – but as far as the ancient Chinese were concerned, the ‘King of Ryukyu’ was the ‘King’ of the entire geographical area defined by this term. Whereas the Chinese term is prosaic (poetically speaking of ‘jade’ and ‘unexplored’ land – the Japanese term might well be practical as it seems to be describing the ‘rope’ that is extensively used in sailing ships, boats, and other floating entities – including the requirement to ‘moor’ such objects in purpose-built ports. The difference in the two-names probably reflects the developing socio-economic conditions prevalent throughout the Island Chain at the time of conception – with around 1500 years separating the development of the two names. Chinese Language Text:

This looks similar in concept to Qinna (擒拿) - Joint Manipulation - or literally 'Catch Grasp'. A limb (or the torso) is seized and stopped from independently moving around its joint(s). When pressure is applied to the joint - moving it in the opposite direction to that which it is supposed to move - then pain is induced. Of course, extreme pressure leads to dislocation of the joint-structure and breakage of the bone shaft. I notice that many of the stances and movements look very similar to Kata and Form combinations. The idea, I assume, is to take control of the opponent's torso or limb, etc.

2024-02-19 China Daily Editor: Li Yan Tongliang's promotion of its proud dragon dance heritage paying off

Cai Mingcan, a 47-year-old artist in Chongqing, Southwest China, who has been preserving and modernizing Tongliang dragon dance for 30 years, is glad to see it gaining popularity, especially among the young. "As the heirs of the dragon, all Chinese love the creature, and we shoulder a responsibility to pass on the dragon culture," he said. Tongliang, a district in Chongqing, claims to be the home of the country's best dragon dance performance, a nationally listed intangible cultural heritage. One of the best practitioners in the area is the National Tongliang Dragon Dance Troupe, which was honoured as such by the Chinese Dragon and Lion Dance Sports Association in 1999. Cai, the only professional artist among a handful of municipal-level Tongliang dragon dance inheritors, became coach of the troupe in 2012. In 2021, the national troupe was integrated into the Tongliang Dragon Art Troupe, which was established that year, and Cai became the art troupe's deputy director and coach. The troupe of more than 50 performers — with an average age of only 21 — consists of the national team and three other teams. Eighteen members are women, and 85 percent of team members are local residents, Cai said. The teams have performed in more than 30 countries and regions, including the United States, Britain, France, Australia, Turkiye, Japan and South Korea. The Tongliang dragon dance has been showcased at such major events as China's National Day celebrations, the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the 2010 Shanghai World Expo. On New Year's Eve in 2017, it wowed audiences when it performed in New York City's Times Square in the US. Cai said there are about 100 types of dragon dance in Tongliang. The troupe performs different types of dragon shows according to the 24 solar terms, including the bamboo dragon show in spring, the lotus dragon show in summer, the straw dragon show in autumn and the fire dragon show in winter. Other common types include the folk dragon and competitive dragon shows. Performances of the latter have won the troupe 78 gold medals in national dragon dance competitions since the 1980s, Cai said. The Tongliang dragon dance dates back to the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties, when people prayed for rain by worshipping the rain-bringing dragon kings, who in Chinese mythology lord over the seas and control the weather. The ritual gradually evolved into a folk recreational activity during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, typically during the Lantern Festival — one of the most important new year celebration events in ancient China. "The dance has continued to thrive and even has profound meanings in the contemporary era," said Cai, adding that in Chinese culture, the mythical creature is associated with power, nobility, fertility, wisdom and auspiciousness. "It also symbolizes an enterprising spirit, solidarity and bravery." Our Hakka gongfu training requires the carrying of heavyweights upon our backs. This represents the hilly terrain the Hakka people lived within throughout the New Territories, Hong Kong. Hakka Clan villages, especially by the 20th century, were often re-constructed upon the top of various hills situated in prominent good (feng shui) positions. The bones must be kept strong for building good health and ensuring longevity. Strong bones allow the bodyweight to drop down through the centre of the bone-marrow into the floor (creating a strong 'root') - and facilitates the rebounding force which is distributed (throughout the skeletal-system) to the striking part of the anatomy - be it a hand, foot, elbow, knee, fore-head or torso, etc. The Hakka people moved into the Guangdong area (that became the 'New Territories' under the British in the 1890s) in the mid-1600s - following the Manchurian invasion of China (which established the foreign 'Qing Dynasty' during 1644 CE). Our 'Chan' (陳) Clan (pronounced 'Chin' in the Hakka language and 'Chan' in the Cantonese language) originally settled at the base of a hill near the coast in the Sai Kung area. I think we probably originated somewhere in Henan province (like many other Hakka Clans that I have investigated). Younger people often carried older relatives on their backs (as part of the required filial piety) up and down the hills - to and from various areas. Chinese families reflect the government and vice versa. One reflects the other whilst the notion of Confucian 'respect' permeates the entire structure. This is true regardless of political system, era, religion or cultural orientation. Many Daoists and Buddhists are Vegetarian - because they respect animals and the environment. When working as farmers - Hakka people carried tools, goods and the products of harvests on their backs between long hours working in the rice fields with the Water Buffalos. The continuous repetition of hand and foot movements - and the standing postures for long hours in the wind and rain - condition the mind and body for genuine Hakka gongfu training. Although there is an 'Iron Ox' gongfu Style (different to our own) - the spirit of the Ox pervades all aspects of the Hakka gongfu styles! Even so, our Hakka Style embodies the spirit of the Bear! We can fighting crouching low - or stand high giving the impression that we are bigger than we actually are! Our developed musculature is like the Ox and the Bear in that it is large, rounded and tough! We can take a beating and still manifest our gongfu Style with ease! We do not go quietly into that dark night! The above video shows Hakka people de-husking rise - with the standing person practicing 'Free Stance, rootedness and knee-striking, etc, and the crouching person showing a low Horse Stance and position for 'Squat-Kicking', etc, whilst demonstrating dextrous hand movements often found in gongfu Forms. Of course, not all Hakka Styles are the same and there is much diversity throughout the Name Clans. Our Chan gongfu is Military-related and can be traced to the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE). I think there used to be a State Gongfu Manual (since lost) issued by the Qin Dynasty as part of the process of turning every village, town and city into a 'Barracks'. Guiding the ploughs through the water and mud at the back of the Water Buffalos reflected the leg, arm and torso positions found within the Hakka gongfu. How the Hakka farmers stood still, stepped forward and back - side to side, tensed and relaxed their muscles, used their eyes and ears, and produced power and learned to give-way - all manifested in the various Hakka gongfu Styles. On Occasion, the Ox is given the day-off and the local people take to 'pulling the plough'! Our Hakka Gongfu is 'Longfist' based. Whereas many Hakka Clans - following our defeat at the end of the Punti-Hakka Clan Wars (1854-1867 CE) - Hakka people were ethnically cleansed into small areas of Guangdong province. Around 20 million people had died in this terrible war (which included the separate but related Taiping Rebellion - a Hakka-led war - fought for different reasons). The original 'Northern' Hakka Styles were persecuted and viewed as the vehicle through which the Hakka people had made war in the South of China (the area they had migrated into). The Hakka are patriotic Han Chinese migrants who fled the foreign invasion of Northern China - but who were not wanted or welcome within Southern China. Since the 1949 Revolution - things are very different today in China - as Hakka and non-Hakka now live side by side in harmony. When the various Hakka Clans 'shortened' the arm and leg movements of their gongfu Styles - to make these arts seem 'Cantonese' in origin - our Hakka Clan lived in a relatively remote area of South East Guangdong province and refused to do this. We practiced our 'Northern' Longfist martial arts in isolation and hid our gongfu in Temples grounds, behind walls and by practicing at night. Master Chan Tin Sang (1924-1993) fought and killed Imperial Japanese soldiers in the New Territories between 1941-1945 using our Hakka gongfu. Around 10,000 Hakka men, women and children were killed in this war fighting the modern Japanese soldiers using bare-hands and feet - and traditional weaponry. Many of our relatives were killed during this time. Master Chan Tin Sang came to the UK in 1956 - as a British Subject - to work for a better life, not because China is a bad place (it is not), but because life in the New Territories under British rule was continuously impoverished. Master Chan Tin Sang worked hard for 10-years before he earned enough money to bring his wife and two daughters to the UK (in 1966) - also as British Subjects. My Chinese relatives were NOT economic migrants, Asylum Seekers, or Refugees. My Chinese relatives do not follow Cults and are free-thinking individuals who are proud to be 'British' whilst supporting Mainland China's right to self-determinate - just like any Western country.

Japanese Karate-Do (General) - 'Mawashi-Uke' (廻し受け): Mawa (廻) = rotation, turning, rounded and circular, shi (し) = four-corners, all-areas and comprensive-cover U (受) = receive, meet, accept and stoically bear (suffer) Ke (け) = stratagem, plan, calculation and measure Okinawan Goju Ryu Karate-Do - 'Toro Gushi-Uke' (虎口受け): Toro Gushi (虎口) = literally 'Tiger-Mouth' envelopes the enemy - and closes inward from all-sides at once U (受) = receive, meet, accept and stoically bear (suffer) Ke (け) = stratagem, plan, calculation and measure Southern China Gongfu Equivalent: Double Butterfly Open-Palm = 双蝶掌 (Shuang Die Zhang) Okinawan Goju-Ryu 'condenses' many of these Southern Gongfu Movements for efficiency. Long stances are shortened whilst reaching arm-movements are brought closer to the body (perhaps adapted for practitioners spending long periods on boats). Many Hakka Gongfu Styles originating in the North progressed through this adaptation process in South China. Our Family Style did not - but virtually all the Clan Styles around our village did. Tora - Tiger - can also be pronounced 'Koko'. In Fujian this can be 'Ho Kho'. Sometimes, despite the literal interpretation of 'Tiger Mouth' - it is used in Chinese and Japanese texts to mean 'Jaws of Death! The Chinese text states that Goju Ryu is a genuine transmission of 'Nan Quan' (Southern Fist). 攻防一体虎口廻受 Attack and defence are integrated - the open tiger's mouth simultaneously envelopes and traps.

Dear Tony Interesting. Thank you for your knowledgeable explanation of sparring - an adult 'tiger playing with a cub'. This inspired me to research 'Ran-Dori' in Japanese-language sources - which is written as '乱取り' - '乱捕り' and 'らん‐どり'. Both of the following Japanese-language Wiki-entries (I have checked the data is correct) should be read side by side to gain an all-round clarity - as the 'Randori' entry does not specifically mention Karate-Do - whilst the 'Kumite' page explains that in some Styles of Karate-Do - 'Kumite' is referred to as 'Randori'. Randori - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate) Kumite - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate) I suspect the inference is that in Okinawan Karate-Do the term 'Randori' is used - whilst in Mainland Japan - the term 'Kumite' is the preferred. Difficult to say, but as you know, 'nuance' and 'implication' is an important part of Japanese communication. What is NOT said is as important (sometimes more so) than what IS said. Perhaps this Yin-Yang observation is just as important for sparring - whatever its origination and purpose. As for the traditional Japanese and Chinese ideograms - this is what we have: 乱取りand 乱捕り 乱 (ran) = chaos, disorder 取 - 捕 (to) = take hold of, gather, control, arrest り(ri) = logic, reason, understanding Therefore, 'Ran-Tori' and 'Ran-Dori' are synonymous - with the concept expressed in its written form as '乱-取り' - ot 'Chaos (Random Movement) - Seize Control of'. What is 'chaotic' in the environment is wilfully taken control of - by imposing an outside order upon it. This suggests that the 'non-controlled' is 'controlled' by the structure of Kata-technique - which is brought to bear by an expert. There also seems to be the suggestion that that which 'moves' - is wilfully brought to 'stillness'. As for a Chinese-language counter-part, perhaps we have: 乱 - 亂 (luan4) = disorderly, unstable, unrest, confused and wild (Japanese = 'turbulent') 取 (qu3) = take hold, fetch, receive, obtain and select り- 理 (li4) = put into order, tidy up, manage, reason, logic and rule It would seem that the Japanese term of 'Ran-Dori' equates to the Chinese term of 'Luan-Quli' - or 'Disorder - (into) Order Rule'. Your reply inspired me to think about what the Japanese '乱' (Ran) - or Chinese equivalent '亂' (luan4) - actually means. What is the definition of the 'disorder' being referenced to when 'Ran-Dori' is being discussed? Therefore, '亂' (luan4) is comprised of a 'left' and 'right' particle: Left Particle = 𤔔 (luan4) means to 'govern' and 'control' - and is structured as follows: a) Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. b) Lower (Inner) Element = 幺 (yao1) - a contraction of '糸' (mi4) which refers to 'thin silk threads'. c) Lower (Outer) Element = 冂 (jiong1) this is a 'comb', 'beater' or 'heddle' - a device to 'order' the silken threads that require weaving. In normal usage, this ideogram denotes the structured boundary that clearly demarks the city limits. Right Particle =乚 (yi3) is a contraction of '隱' (yin3) - meaning to 'hide', 'conceal' or 'cover-up', etc, as in 'something is missing'. It can also refer to a required process that is 'profound', 'subtle' and 'delicate' - but which is currently 'lacking'. It may also mean 'secret' and 'inward' or 'inner', etc. I would say that 'obscuration' is what this ideogram refers to in its meaning. Conclusion The literal meaning of '亂' (luan4) [or 'Ran' in 'Ran-dori] - is that it refers to a lack of skilful organising ability (disorder and confusion). The thin silk threads are not placed correctly on the wooden frame (loom) - and therefore cannot be 'weaved' together in an orderly fashion. This entire process lacks the required profound knowledge and experience to achieve the objective - thus the hands (and body) cannot be used in the appropriate manner. Ran-Dori (乱捕り), as a complete process, suggests that it is the opposite of the above 'lack of skill' that is require in sparring. Not only is this skill required, but 'ri' (li) element (理 - li3) - suggests a 'regulation' and an 'administration' (premised upon logic and reason) - such as the profound skill required to 'cut' and 'polish' jade. I was discussing Randori with another language expert and they gave me more data which I have added to this paragraph: 'Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. ' I was curious as to why the two hands were so specific in their orientation and my colleague said that they are clearly carrying out the process required for ancient 'weaving'. One hand is laying the 'warp' - or 'vertical' thread down through the loom - whilst the other right hand is performing the function of 'weaving' multiple 'weft' threads into place horizontally across the loom! As a matter of comparison - the 'Kumi' (組) in Kumi-te (組手) - Chinese 'Zu Shou' - means to 'weave continuously'. This translates as 'to be skilful' (the silken threads are skilfully woven [糹-si1] together forever - like the longevity of a sacrificial vessel [且 - qie3] - which are traditionally made out of stone). Therefore, Kumi-te literally refers to a 'continuous skill that unfolds through the hand'. This may be compared to the term 'Ran-Dori' which refers to a 'missing skill' that has yet to be 'acquired' and is in the midst of 'being acquired' (through developmental training) - whilst Kumi-te implies that the required skill is already present and should manifest automatically.

|

AuthorShifu Adrian Chan-Wyles (b. 1967) - Lineage (Generational) Inheritor of the Ch'an Dao Hakka Gongfu System. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed