|

The Island known as ‘Okinawa’ lies off of the South-West coast of Japan - forming part of the Ryukyu Island Chain - and is expressed in Japanese (Kanji) ideograms as ‘沖縄’. This name may be deconstructed as follows: a) oki (沖) = expanse of open water b) nawa (縄)= rope or thread The name appears to be a direct description of the numerous islands that comprise ‘Okinawa’ – which are themselves a substantial (Southern) part of the larger Ryukyu Island Chain. Perhaps the geographical placement and general shape of the islands was seen from high mountain-tops, surveyed in passing ships and/or observed from upon high by those who flew in the ‘Battle Kites’ known to exist within medieval Japan. Whatever the case, the Okinawa Island Chain is said to resemble a meandering rope lying across the surface of the water. I have read that this area first became known to China under the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) – but was not formally recognised by the Imperial Court until the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). This is when diplomatic and cultural contact with the King (of what was then termed the 'Liu Qiu' [琉球] Islands) was established - known today by the Japanese transliteration of 'Ryukyu'. 琉 (liu2) = sparkling-stone, jade, mining-stone (from previously uncultivated land), precious-stone, arriving, and breaking through (to a place far away - and situated on the fringes of the known world) 球 (qui2) = beautiful-jade, polished-jade, refined-jade, jade percussion instrument, earth, ball, and pearl. The Chinese Mariners must have been taken with the beauty of the Ryukyu Islands - as the term '玉' (yu4) – or ‘jade’ - appears as the dominant left-hand particle of both ideograms forming the name ‘Liu Qiu’. From the Tang Dynasty onwards, the Liu Qiu Islands were considered a distant (but important) part of the Tributary System of Imperial China. In return for a continuous show of annual respect (usually in the form of expensive gifts and/or elements of trade, etc) China shared her extensive culture. It was not until 1872 CE, however, that Imperial Japan took decisive action to annex all of the ‘Ryukyu’ Islands – and it was around this time that the term ‘Okinawa’ was developed to describe the Southern two-thirds of the Ryukyu Island Chain – now a ‘Prefecture’ of Japan. This history explains why the ideograms for ‘Okinawa’ are written in (Japanese) ‘Kanji’ - and are not obviously ‘Chinese’ in structure (as is the far older name of ‘Liu Qiu’). Is it possible to ‘reverse-engineer’ the Kanji ideograms associated with the name ‘Okinawa’ (沖縄) and work backwards as it were – to the original Chinese ideograms? The answer is ‘yes’ – as such an exercise might well shed some more light on the meaning of the name itself. Japanese - 縄 (nawa) = Chinese – ‘繩’ (sheng2) When adjusted in this manner - the Japanese name of ‘Okinawa’ (沖縄) is rendered into the Chinese language as ‘Chongsheng’ (沖繩). Whereas the first ‘Kanji’ ideogram of ‘沖’ (oki) remains identical with its Chinese counterpart of ‘沖’ (chong) - the second ‘Kanji’ ideogram (縄 - nawa) undergoes a substantial modification (繩 - sheng). From this improved data a more precise definition of the name ‘Okinawa’ can be ascertained through the assessment of the Chinese ideograms that serve as the foundation of the Kanji ideograms – working from the assumption that this meaning is still culturally implied through the use of ‘Kanji’ in Japan – even if such a meaning is not readily observable within the structure of the ‘Kanji’ ideograms themselves. 沖 (chong1) is comprised of a left and a right particle: Left-Particle = ‘氵’ which is a contraction of ‘水’ (shui3) – meaning water, river, flood, expanse of water, and liquid, etc. Right-Particle = ‘中’ (zhong1) refers to the concept of something being ‘central’, in the ‘middle’, or being perfectly ‘balanced’. It can also refer to an ‘arrow’ hitting the ‘centre’ with a perfect ease. Therefore, the use of 沖 (chong1) in this context - probably refers to an object that centrally exists within a body of water. 繩 (sheng2) is comprised of a left and right particle. Left-Particle = ‘糹’ which is a contraction of ‘糸’ (mi4) – meaning something that resembles a ‘silken thread’, a ‘thin’ and ‘flexible’ cord, a ‘rope’ or ‘string’, etc. This may also refer to the act of ‘weaving’ or to an object (like a rope, string, or strand) which is ‘woven’ into existence – perhaps implying a ‘cohesion’ attained through an ‘inter-locking’ agency, etc. Right-Particle = ‘黽’ (meng3) – this was originally written as a depiction of a type of frog – but evolved to be used generally to describe the act of ‘striving’, ‘endeavouring’, or ‘working hard’ (nin3). However, I am of the opinion that more practical attributes are at work in this instance. An old (but simplified) version of this ideogram is ‘黾’ – which demonstrates a clarification of what used to be a ‘frog’: This explains why there is said to be an ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ element to this particle: Upper-Element = ‘口’ (kou3) – signifies an ‘open mouth’, ‘entrance’, ‘mouth of a river’, and ‘port’. This can also denote a ‘boundary’ and a ‘hole’ or ‘indent’. This used to represent the head of a frog. Lower-Element = ‘电’ (dian4) – denotes ‘forked-lightning’, ‘energy’ and ‘electricity’, etc. Although evolving from the body of a frog – this element conveys not only the overt power of lightning – but perhaps retains something of the ‘shape’ of forked lightning in its usage as a noun. Perhaps 繩 (sheng2) is a descriptive term used to describe a port that allows entry to a string of islands which seem to take the shape of a rope that geographically unfurls - like forked lightning traversing the sky. Conclusion The term ‘Chongsheng’ (沖繩) – or ‘Okinawa’ - probably refers to a string of islands (and ports) which exist within a broad expanse of open sea - like a rope floating upon the surface of the water (the shape of which resembles that of forked-lightning). This place may be difficult to reach – and the people encountered may be very hard working. It is highly likely that these islands seem to float like a frog on the surface of the water – hence the selection of these ideograms. Of course, the post-1872 Japanese Authorities chose to use the Kanji ideograms of ‘沖縄’ to convey the concept and meaning of the name ‘Oki-Nawa’. In Chinese language texts, I do not see Okinawa referred to as an isolated unit of geographical description. This is because Chinese literature refers to the entire Chain of Islands by the far older and more traditional name of 'Liu Qiu' (琉球) – which was politically acknowledged through ancient diplomatic exchange. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the post-1872 Japanese Authorities did not abolish this Chinese name – but borrowed it – simply transliterating it into the now well-known ‘Ryukyu’ Islands. Okinawa is only around two-thirds of the Southern-Central area of the Ryukyu Islands – but as far as the ancient Chinese were concerned, the ‘King of Ryukyu’ was the ‘King’ of the entire geographical area defined by this term. Whereas the Chinese term is prosaic (poetically speaking of ‘jade’ and ‘unexplored’ land – the Japanese term might well be practical as it seems to be describing the ‘rope’ that is extensively used in sailing ships, boats, and other floating entities – including the requirement to ‘moor’ such objects in purpose-built ports. The difference in the two-names probably reflects the developing socio-economic conditions prevalent throughout the Island Chain at the time of conception – with around 1500 years separating the development of the two names. Chinese Language Text:

0 Comments

It is said that around 1926, the ethnic Chinese man named ‘Go Genki’ (呉賢貴) or ‘Wu Xiangui (1886-1940) – migrated to Okinawa and became a Japanese citizen. My view is that the name ‘呉賢貴’ (Wu Xian Gui) is a transliteration of this person’s chosen Japanese name – and is not his given ethnic ‘Chinese’ birth name. I believe this is true despite many Western scholars treating this transliteration as if it were his ‘true’ and ‘genuine’ ethnic Chinese name. Furthermore, Japanese language historical texts state that this Master of Fujian ‘White Crane Fist’ (白鶴拳 - Bai He Quan) married an Okinawan woman surnamed ‘Yoshihara’ (吉原 - Ji Yuan) - and that he took this surname as his own. This surname is common in Japan and the Ryukyu Islands and has more than one origination. This name literally translates as ‘Lucky Origination’ - and although one branch is linked to the Japanese imperial house – many others are simply linked to ‘good’ and ‘pleasant’ places. If Go Genki took this name, then he would have been known as ‘Yoshihara Genki’ or ‘吉原 賢貴’ - if these names (and facts) are correct. Go Genki is believed to have taught Miyagi Chojun the ‘Open Hand of the Crane’ exercise. This is recorded within Japanese language texts as '鶴の手'. The first and third ideograms - '鶴’ (he4) meaning ‘Crane’ and ‘手’ (shou3) meaning ‘Open-Hand’ - are of Chinese language origination, whilst the second character (‘の’ - ‘no’) is entirely ‘Japanese’ in nature. This phrase can be read in the Japanese language as: a) 鶴 (he4) - Crane = ‘か’ (Kaku), ‘つる’ (Tsuru) and ‘ず’ (Zu), etc. b) の (no) - Hiragana Character – ‘Belonging to’, 'Possessing’ and ‘Pertaining to’, etc. c) 手 (shou3) - Open-Hand = ‘ず’ (Zu), ‘て’ (Te) and ‘手’ (Te), etc. As this training method has been transmitted into the practice of modern Goju Ryu Karate-Do - the above concept can be compared to its contemporary counter-part – namely that of ‘Sticky-Hands’ generally referred to as ‘Kakie’ (カキエ). This analysis reveals a startling correlation in that ‘Kaku’ (か) - Japanese for ‘Crane’ - shares the first particle of ‘Kakie’, namely the Katakana particle of ‘カ’! This is said to be linked to the Chinese language ideogram ‘加’ (jia1). This ideogram is composed of two particles: Left Particle = ‘力’ (li4) - meaning a ‘plough’ used to cultivate the land. The foot presses down so that the plough may ‘cut’ into the soil whilst being firmly rooted. Right Particle = ‘口’ (kou3) - referring to an ‘open mouth’ which is calling-out encouragement to the oxen pulling the plough! During the Heian Period of Japan (794-1185 CE), however, the Chinese ideogram ‘加’ (jia1) was modified and reduced to only the left-hand particle – forming the Japanese Katakana letter of ‘カ’ (and the Hiragana letter of ‘か’). Interestingly, the Japanese term ‘Kaku’ (meaning ‘Crane’) is written as ‘か’ (mirroring the ‘Hiragana’ letter) - but in this instance it is a direct conjunction of the Chinese ideogram - 鶴 (he4), taking on a more specific and direct meaning. The Chinese ideogram - 鶴 (he4) or ‘Crane’ - is comprised of the following constituting particles: 1) Left-Hand Particle: 寉 (he4) - Archaic – Meaning ‘Crane’ and ‘Bird’. The Japanese equivalents for reading this Chinese particle include ‘か’ (Kaku) and ‘つる’ (Tsuru) - all referring to a ‘Crane’. 2) Right-Hand Particle: 鳥 (niao3) - ‘Bird’ and ‘To Breed’ Birds. The Japanese equivalents for reading this Chinese particle include ‘か’ (Ka) and ‘とり’ (Tori) - all referring to a ‘Bird’ and/or ‘Chicken’. The Japanese term ‘か’ (Kaku) - although a recognised conjunction of the Chinese ideogram 鶴 (he4) (meaning ‘Crane’) - is used today to refer to a ‘Mosquito’ (although an archaic interpretation also refers to a ‘deer’). Perhaps the association between a ‘Crane’ and a ‘Mosquito’ refers to both being flying creatures that are known to be ‘dangerous’ due to their ‘biting-stinging’ capabilities. What links the Japanese term ‘か’ (Kaku) - or ‘Crane’ - to the Goju Ryu Karate-Do practice of ‘カキエ’ (Kakie) - or ‘Sticky-Hands’ - is the Japanese (Katakana) language particle of ‘カ’. This corresponds to the ‘Hiragana’ particle of ‘か’ (also pronounced ‘Ka’ when discussed as the sixth syllable of the gojuon order). In and of itself, ‘カ’ (Ka) indicates a ‘question’ or a ‘sense of doubt’ when used with general Japanese language discourse – although it is also used as part of hundreds of other concepts, from Buddhist enlightenment to a glowing fire and many others! Whatever the case, when ‘か’ (Kaku) is used within the context of Goju Ryu Karate-Do - the particle ‘カ’ (Ka) forms an important constituting element of the Japanese word for ‘Crane’. In this instance, the fighting abilities of the Crane are emphasised. The Crane is defined as a large, long-legged bird of the Gruidae family – which can be dangerous because of its fierce squawking and deceptive movements – coupled with the use of its long and sharp beak, its strong kicking and its dangerous ability to powerfully deflect blows through the use of its wings. The alternative Japanese term for ‘Crane’ - ‘つる’ (Tsuru) - does not refer to the Crane’s fighting ability – but rather the length of its slender legs, body and beak. This is because ‘つる’ (Tsuru) is linked to a description of a ‘vine’, ‘string’ or ‘twine’, etc, - referring instead to the slim dimensions of the ‘Crane’ rather than any combative or fighting abilities it may possess. (Indeed, ‘つる’ (Tsuru), due to its association with ‘fishing’ and ‘hooks’, etc., also carries the meaning of ‘to hang’ - as if ‘hanging’ from a hook – perhaps referring to a ‘Crane’ as it soars through the sky – or perhaps as it stands upon one-leg – giving the impression that its solid stance has some other supporting device). As the practice of ‘カキエ’ (Kakie) is said be ‘Crane-like’ - then it is logical to assume that the practice of '鶴の手' (Kaku No Te) - or ‘Open-Hand of the Crane’ - must be directly related to the practice of ‘カキエ’ (Kakie). I suspect that as the Master to Disciple transmission was traditionally premised upon physical action and spoken instruction, the Chinese practice of ‘鶴の手’ (which could be pronounced in China as ‘He De Shou’ or more succinctly as ‘He Shou’) was passed on in Okinawa as ‘Kaku No Te’ - which was then transformed into ‘Kakie’ (カキエ) overtime – being finally written down through the manner in which the description of the practice had evolved. The original emphasis upon the ‘Crane’ as a noun – was transformed into an emphasis of the dynamics of the practice itself (as a ‘verb’). I believe the clue to this association is the inclusion of the Japanese particle ‘カ’ (Ka) in both ‘か’ (Kaku) - or ‘Crane’ - and in ‘カキエ’ (Kakie) - ‘Sticky-Hands'.

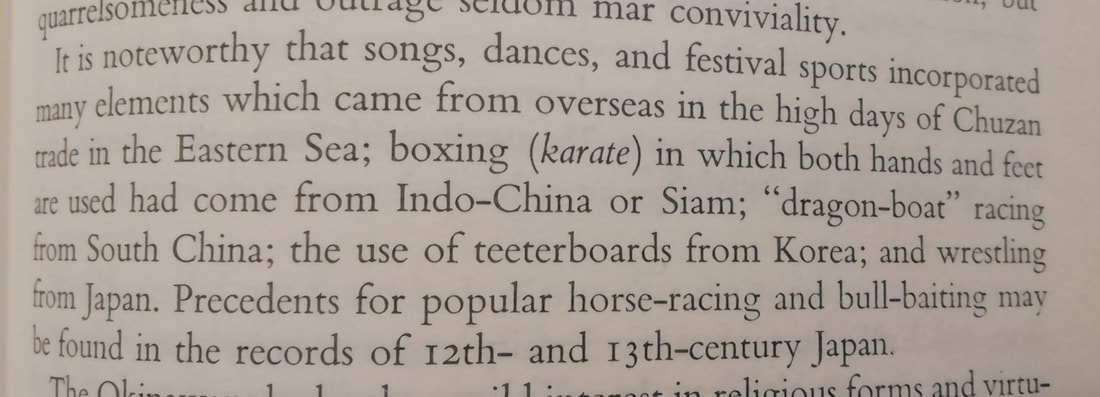

Karate is mentioned just once, and even then, more or less in haste, and certainty not in any historical depth! This is disappointing from a book comprising of over 550 pages! Professor Mitsugu Sakihara provides a fascinating 'Afterword' and about ten-pages of corrections, deletions and other necessary 'errata' clarifications. Again, with a ground-breaking book of such historical scope and ambition - this type of 'correction' by an Asian academic fully armed with the latest research is nothing to be ashamed of - as a vast majority of the historical wealth presented within this books stands up to Japanese and Okinawan academic scrutiny! Of course, we must all be careful to correctly discern 'fact' from 'fiction', 'truth' from 'myth' and 'lies' from 'truth'! I present this data to add the over-all research into the fascinating history of Okinawan Karate-Do - much of which originates in Southern China, indigenous Okinawan martial culture and it would seem - the fighting arts of South-East Asia (Thailand, Myanmar and Cambodia, etc) or even Indo-China (Vietnam)! George Kerr's research into the origin of Karate-Do is not referenced (so we do not know where he acquired his information) - but he is of the opinion that 'Karate' was brought back to the Ryukyu Islands by Ryukyu sailors visiting (and training in the martial arts of) South-East Asia and/or Vietnam - and not China! I have heard a similar idea expressed in some Japanese and Chinese language articles - but only in as much as suggesting 'some' Karate-Do techniques (such as the 'round-house' kick) originated within the martial culture of South-East Asia - but not the complete system! Whatever the case, to consider all the available data - the data must be made available to all - and freedom of thought will do the rest!

Miyagi Chojun (1888-1953) – the founder of Goju Ryu Karate-Do - was born in Naha City on April 25th, 1888. The Miyagi family was of the ‘noble’ (ancient ‘Ryukyu’) class and was very wealthy due to supplying Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) to the Ryukyu Royal Family. This meant that the Miyagi family members were travelling continuously backwards and forwards to imperial China – and possessed continuous ‘official’ clearance from a) the Okinawan Authorities, b) the Japanese Authorities and c) the Chinese Authorities. For most ordinary people this bureaucracy was almost impossible to navigate – and even if navigated successfully – it usually applied to only a ‘single’ return journey! It was this established trade routes between the Ryukyu Island and Imperial China that Miyagi Chojun would use to facilitate his travelling to Mainland China (which might well give credence to his 1915, 1916 and 1936 visits – with ‘1916’ often being the most disputed visitation). The Miyagi family were known locally as a ‘White Silk Seal’ (素封 - Su Feng) - or very wealthy - family. This is written in the Japanese script as そほうか’ - and refers to a family with large land holdings and substantial wealth assets. Miyagi Chojun’s father was named ‘Miyagi Chosho’ (宫城長祥) - who was the third of three sons born in his generation of the Miyagi family. Unfortunately, Miyagi Chosho died early on – and when Miyagi Chojun was three years old (during 1891) he was adopted by relatives from the primary branch of the Miyagi family (which possessed no male heir). Therefore, from an early age, Miyagi Chojun became the official heir – legally designated to inherit the entire Miyagi family fortune! According to biographical details supplied by Aragaki Ryuko [新垣隆功] (1875–1961) - the mother of Miyagi Chojun took him to a neighbour to begin martial arts training when he was eleven years old (during 1899). When Mr Aragaki Ryuko recalled his earliest memories of a young Mr Miyagi Chojun - he described him as an active and competitive child who often caused trouble with other children! Aragaki Ryuko, however, also recognised that Miyagi Chojun was also very talented when it came to fighting! Furthermore, although young, he exhibited a very serious attitude when training in martial arts and retained a sense of utmost discipline! Even when tired – he would never give-up and would always continue to try and move correctly and without error! Aragaki Ryuko carefully observed the behaviour of Miyagi Chojun for three-years to ensure that what he was seeing was correct. Only after this period of character-testing did Aragaki Ryuko stake his own reputation on recommending Miyagi Chojun for training with Master Higaonna Kanryo (1853-1915)! When Higaonna Kanryo accepted this youth as his ‘disciple’ - Miyagi Chojun was aged fourteen-years-old (during 1902). This means that Miyagi Chojun trained with Higaonna Kanryo between 1902-1915. This equals to thirteen-years – with two-years (1910-1912) taken-out for Miyagi Chojun’s military service in the Imperial Japanese Army (in Kyushu). Higaonna Kanryo was very strict and demanded very high levels of self-discipline and commitment from his students! He trained his students so severely that the purpose was to make those with weak characters ‘choose’ to quit training because they found it ‘too difficult’. Higaonna Kanryo would say that everything they needed was provided for their training right outside their front doors – and that they did not have to travel, seek out or attempt to communicate or negotiate! If, after all this pampering they were still unable to commit themselves to serious training – what good were they? Higaonna Kanryo would continuously advise students to go home and take-up a less demanding pastime! He wanted to see if they possessed the courage to come back the next day and face his wraith for them daring to defy his instruction! Miyagi Chojun kept returning and setting himself the daily task of using all the provided body-conditioning equipment surrounding Higaonna Kanryo’s home – whilst showing ‘respect’ NEVER giving in to the provocation to give-up! The more intense Higaonna Kanryo’s pressure became – the ‘calmer’ Miyagi Chojun’s mind would become and the ‘better’ his martial technique would manifest! This impressed Master Higaonna Kanryo – who said his teachers in China were just as hard upon him as he was upon his own students in Okinawa. As a consequence, Miyagi Chojun developed a very powerful (and ‘rooted’ to the ground) martial technique so that he was able to strike with considerable force through a ‘hardened’ and ‘toughened’ body structure that could be ‘relaxed’ inbetween bouts of required ‘tension’! Furthermore, when required, his body could absorb, deflect and redirect all incoming power from the blows of others! Chinese Language Source: 宫城长顺先生生平介绍(转载) 剛柔流实际的创立人是宫城长顺先生(1888-1953)。宫城长顺先生生于1888年4月25日,於那霸市出生。宫城家是以进口中国药材供应琉球王府御用的经商家族,琉球时代上等位阶士族的后裔,在那霸闻名的素封家 (そほうか,指拥有大土地,大資産的家族),宫城长顺先生的父亲是宫城家三男宫城長祥,早亡,三岁时宫城长顺先生被属于无亲子的亲戚领养并且从小被指定为宫城家业的继承人,家道富裕。

宫城长顺先生11岁开始由母亲带他到其邻居泊手师父新垣隆功先生(1875-1961)门下习武。(新垣隆功先生便是国际冲绳刚柔流空手道连盟IOGKF范士新垣修一先生的祖父,而且新垣隆功先生是位曾经在公开比武中打赢了本部朝基的冲绳空手名人)。新垣隆功先生回顾起年幼的宫城长顺先生时,描述他是个好动并且好胜的孩子,时常与其他孩童闹事。但新垣隆功先生见宫城长顺先生天资过人,习武认真,3年后,即宫城长顺先生14岁那年推荐他到东恩纳宽量先生门下习武。在东恩纳宽量先生极度严格的训练下,宫城长顺先生的性格逐渐变得稳重谦恭。 学生时期的宫城长顺先生每日下课后便跑步十几公里到达其师父之住处训练。并且他将沿途各种大小的石头当成举重或者击打的训练器具。据老一代的前辈描述,宫城长顺先生在学校里体育方面表现出色,特别是体操单杠运动的好手,他也曾经是学校中的柔道好手,但因为出手过重而最后校方要求他退出柔道训练。宫城长顺先生年轻时在也经常参加冲绳的摔跤赛事,但出手重并且经常使用些摔跤之外的技艺最后导致其他摔跤手不欢迎他参与赛事。因他养父临终前劝他别为了摔跤与他人结仇,宫城长顺先生放弃了摔跤。 作者:猫爷习 https://www.bilibili.com/read/cv1652712/ 出处:bilibili After graduating, Mr Miyagi Chojun worked in a local Okinawan bank for one year. This was the ‘147 Bank’. After working hard for one year – the Elders of the Miyagi family were of the opinion that the family finances were secure – and they ordered Miiyagi Chojun to pursue a career as a full-time martial arts practitioner-instructor. This decision was premised upon the fame Miyagi Chojun had already built-up as a young man on the island for his psychological and physical toughness – and how he had managed to survive the severely ‘strict’ martial arts training of his teacher – Higaonna Kanryo! Master Higaonna Kanryo was very strict, and his training was so difficult that many young men could not stand it for long – despite being full of youthful vigour! Everyday Miyagi Chojun would run 12 kilometres per day to reach Higaonna Kanryo’s home for training – often carrying heavy rocks along the way! He would also stop occasionally to punch and kick certain rocks designated by his teacher! So strong did this make Miyagi Chojun that when he wrestled – his movements were far too strong and powerful for many of his opponents to stand! Bones were broken and joints dislocated – resulting in Miyagi Chojun being expelled from the Okinawan Wrestling Classes! During 1908, Mr Miyagi Chojun was married and settled down to family life. The Miyagi family business consisted of importing very high-class Chinese medicines which were then provided to the Ryukyu Royal Family. Then, during 1910, Miyagi Chojun was conscripted for two-years into the Imperial Japanese Army – with his military training taking place in Kyushu – Mainland Japan. The tough training under Higaonna Kanryo had moulded the mind and body of Miyagi Chojun – making him both strong in appearance (and ability) but humble in attitude. Before he left for his military training, Higaonna Kanryo taught Miyagi Chojun the ‘Stick Law’ (棒法 - Bang Fa) - possibly the skilful use of the ‘club’ or ‘truncheon’! He also taught Miyagi Chojun how to ‘Attack Correctly with the Open-Hand' (手攻击 - Shou Gong Ji) for future self-defence requirements! Although Okinawans are often discriminated against by the Japanese during military training – as Mr. Miyagi Chojun possessed excellent hand-to-hand combat skills (and unusual physical strength) - he was assigned by the Japanese Officers as the ‘Hand-to-Hand Combat Instructor’ of his squad! After a year of military training, Mr Miyagi Chojun was promoted to the rank of ‘Corporal’ and applied for transfer to the Medical Unit. Here, he learned an in-depth knowledge about human body structure – a profound understanding of biology that assisted his ability to apply scientific knowledge to martial arts training methods later during his life. During that year Miyagi Chojun also joined a local Judo Club to assist his all-round fitness and training development. During November 1912 - Miyagi Chojun completed his military training and returned to Naha City to continue his martial arts training under Higaonna Kanryo. After returning to Okinawa a ‘Party’ was held during which Miyagi Chojun was ‘attacked’ for no reason by a famous Okinawan martial artist known as ‘Motobu Choki’! Miyagi Chojun, without hesitation, swiftly applied an over-powering strength that immediately subdued the attacker with ease in front of many witnesses! This matter was highly publicised at the time (1913-1914) when Miyagi Chojun was 26 years old! Chinese Language Source: 宫城长顺先生生平介绍(转载) 剛柔流实际的创立人是宫城长顺先生(1888-1953)。宫城长顺先生生于1888年4月25日,於那霸市出生。宫城家是以进口中国药材供应琉球王府御用的经商家族,琉球时代上等位阶士族的后裔,在那霸闻名的素封家 (そほうか,指拥有大土地,大資産的家族),宫城长顺先生的父亲是宫城家三男宫城長祥,早亡,三岁时宫城长顺先生被属于无亲子的亲戚领养并且从小被指定为宫城家业的继承人,家道富裕。 作者:猫爷习

学生时期的宫城长顺先生每日下课后便跑步十几公里到达其师父之住处训练。并且他将沿途各种大小的石头当成举重或者击打的训练器具。据老一代的前辈描述,宫城长顺先生在学校里体育方面表现出色,特别是体操单杠运动的好手,他也曾经是学校中的柔道好手,但因为出手过重而最后校方要求他退出柔道训练。宫城长顺先生年轻时在也经常参加冲绳的摔跤赛事,但出手重并且经常使用些摔跤之外的技艺最后导致其他摔跤手不欢迎他参与赛事。因他养父临终前劝他别为了摔跤与他人结仇,宫城长顺先生放弃了摔跤。 作者:猫爷习 学校毕业后,宫城长顺先生在当地一所银行里就职一年 ( 一百四十七银行)。一年后他家族长辈认为家族财力足以支撑他的武术事业并且要求他辞掉银行里的工作。宫城长顺先生1908 年左右结婚,1910年被征召到日本九州进行两年的军训。在走之前,东恩纳宽量先生教了他一套棒法以及贯手攻击的正确方式作为来日防身之用。军训中虽然冲绳人常被日本人歧视,但是因为宫城长顺先生徒手搏斗技艺和体力超群,因此被军官器重指派为所属小队的徒手搏斗指导员。一年之后宫城长顺先生升级为下士,申请调到医务部队服役,在此他学习了许多与人体结构有关系的知识,对他后来设计各种训练运动大有帮助。这一年内他也加入了当地一个柔道馆的训练。1912年 11月宫城长顺先生完成了军训后回到那霸继续在东恩纳宽量先生门下进行空手道的训练。 回到冲绳后,在一次的聚会上宫城长顺先生受到冲绳著名的打架好手本部朝基的挑拨时瞬间用他过人的力量将本部朝基制服。后来此事被在场的其他人宣传出去,而此时的宫城长顺先生大概26岁 (1913~1914年左右)。 作者:猫爷习 https://www.bilibili.com/read/cv1652712/ 出处:bilibili Higaonna Kanryo (1853-1915) travelled from his home in Naha City (Ryukyu) to Fuzhou (Fujian province) between 1867-1881 CE. There is no existing (corroborating) evidence that supports the idea that this journey took place either in what is today called ‘Okinawa’, or what is still known as ‘Fuzhou’ in China. Numerous Revolutions, invasions and wars are blamed for the lack of material evidence in China – whilst the 1945 Battle of Okinawa is blamed for all the historical evidence being destroyed in that place. Of course, this observation assumes that such ‘evidence’ existed in the first place. What are the details that can be stated with reasonable assuredness?

1) A man named ‘Higaonna Kanryo’ existed. 2) He was born during the year 1853 CE. 3) He died during the year 1915 CE. 4) His primary disciple was Miyagi Chojun (1888-1953). 5) What we ‘know’ about Higaonna Kanryo derives from Miyagi Chojun. 6) The ‘nine’ martial ‘sets’ or ‘patterns’ attributed to Higaonna Kanryo possess a certain similarity to the various styles that comprise the ‘Southern Fist’ (南拳 - Nan Quan). 7) The name of his ethnic Chinese martial arts teacher in Fuzhou (Southern China) is said to be ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’. 8) Despite most of the martial ‘sets’ looking like various forms of ‘Southern Fist’ styles that nevertheless maintain ‘Northern’ looking ‘Horse Stances’ - the gongfu art that ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ specialised in is said to have been Fujian ‘White Crane Fist’ (白鶴拳 - Bai He Quan) - with the ‘Sanchin’ (三戦 - San Zhan) or ‘Three Battles’ Form – which Higaonna Kanryo altered by changing finger-strikes to closed-Fists, etc. 9) This ‘Southern Fist’ collection of Chinese martial arts was integrated with Ryukyu ‘Ti’, ‘Di’ or ‘Te’ (手) i.e., ‘Hand’ - and formed ‘Naha Te’ (那覇手). Higaonna Kanryo’s strand of ‘Naha Te’ formed the foundation of Miyagi Chojun’s ‘Goju Ryu Karate-Do' (or ‘Hard-Soft’ Empty-Hand Way) - registered as a ‘Japanese’ martial art during 1936. Although most of the above can be disputed, the reality of most of it lies in the existence of a) the graves of Higaonna Kanryo and Miyagi Chojun – and b) the techniques preserved within the movements of Goju Ryu Karate-Do. A central point of contention is ‘who’ was ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’? Although this issue has been solved within Mainland Chinese academia in 1989 (as Ryu Ryu Ko being the Chinese martial arts Master of ‘Xie Chongxiang’ [谢崇祥] 1852-1930) - this is not the case in the West or within a number of Japanese and Okinawan martial lineages (that refuse to accept the authority of ethnic Chinese historians). Why this is does not concern me here, but what I am concerned about is the lack of ‘logic’ (and ‘inverted’ thinking) surrounding the issue of ‘who’ Ryu Ryu Ko was. a) Ryu Ryu Ko = the Okinawan ‘phonetical’ pronunciation of an ethnic Chinese martial arts teacher living in Fujian province. b) As Higaonna Kanryo could not read, write or speak the Chinese language (despite being a descendent of ethnic Chinese migrants to Ryukyu in 1392 CE), he did not possess the ability to correctly hear, pronounce or write the ‘Chinese’ name of ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ - but could only ‘approximate’ its sound. c) Higaonna Kanryo did NOT bring back any written evidence of the name of ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ using Chinese language ideograms. The fact that the Fujian dialect was used to pronounce this name is immaterial as ALL Chinese ethnic groups use exactly the same ideograms to record their names in written form. d) Higaonna Kanryo’s ethnic Chinese surname is ‘Shen’ (慎) as pronounced in the Beijing dialect - but elsewhere exactly the same ideogram is pronounced (and ‘phonetically’ spelt in other languages) quite differently: i) Guangdong (慎) = ‘San’ ii) Hakka Dialect (慎) = ‘Sum’ (Sixian) and ‘Sem’ (Meixian, Guangdong) iii) Eastern Min – Fujian (慎) = ‘Seng’ iv) Southern Min – Fujian (慎) = ‘Sin’ or ‘Sim’ (Hokkien), ‘Sim’ (Teochew) and ‘Sim’ (Peng'im) ‘Sim’ e) The people in the Fuzhou area used to speak only the ‘Southern Min’ dialect. Given that Higaonna Kanryo’s Chinese name was ‘慎善熙’ (Shen Shanxi) - he may well have been known as ‘Sim Sianhi’ in the local dialect. The pronunciation shifts and the phonetic representation alters as the names traverse the hinterlands of China – but the foundational Chinese ideograms stay exactly the same. Higaonna Kanyro’s Chinese name means: Surname: 慎 (shen4) = 340th Surname included in the book entitled ‘Hundreds of Chinese Clan Names’ (百家姓 - Bai Jia Xing) - and means ‘Those Who Become Prominent Through Being Cautious’. This surname may have originated with the ‘Mohist’ scholar known as ‘Qin Huaxi’ (禽滑釐) who lived during the latter part of the ‘State of Song’ (宋國 - Song Guo) [1046 – 286 BCE]. As the scholar – Mozi (墨子) lived between 468 - 376 BCE – Qin Huaxi must have existed at some point between 376 – 286 BCE. Later, the title of ‘慎子’ (Shen Zi) was conferred upon Qin Huaxi (or ‘Cautious Scholar’) and this is thought to be the origin of this surname. First-Name = ‘善’ (shan4) - ‘Virtuous’ First-Name = ‘熙’ (xi1) - ‘Glorious’ What of ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’? There are no Chinese ideograms available from the time of Higaonna Kanryo’s visit to China. As ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ is a phonetic representation in Okinawa (now a Prefecture of Japan) - the Okinawans have used modified (or ‘distorted’) Chinese ideograms to represent these phonetic symbols. The three modified ‘Kanji’ Japanese ideograms used are ‘劉龍公’ or ‘Liu Longgong’. To an experienced reader of the Chinese written script, it is obvious that these three ideograms are not correct Chinese ideograms – and therefore cannot be representative of a genuine Chinese name. This situation has derived from the Japanese people ‘altering’ the structure and meaning of the Chinese ideograms that once formed the historical foundation of the Japanese system of reading and writing. In the West it is common for scholars and general readers alike to incorrectly assume that the above three Japanese ideograms represent the Chinese spelling of ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ - and that Higaonna Kanryo brought these ideograms back with him from China – when in fact none of this is true and is a product of a general ignorance in the West of the Chinese and Japanese languages. (Technically speaking, it is the altered structure of the second ideogram - ‘龍’ [long2] - which modifies the interpretation of the other two ideograms and confirms the ‘Japanese’ character of the entire expression). These three characters were ‘assigned’ by Japanese speakers to ‘represent’ the sound of the name of ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ to fellow Japanese speakers: 1) ‘劉’ (Liu3) = ‘Ryu’, ‘Riu’ or ‘Ru’ in Japanese phonetic representation. Although this ideogram is found in China, in Fuzhou (when used as a ‘surname’) it is more likely to be pronounced as ‘Lau’ and not ‘Liu’ as continuously asserted by various other non-Chinese sources. Correct Historical Sequence: a) ‘Ryu’, ‘Riu’ or ‘Ru’ - b) ‘劉’ (Liu3) Incorrect Historical Sequence: a) ‘劉’ (Liu3) - b) ‘Ryu’, ‘Riu’ or ‘Ru’ 2) ‘龍’ (long2) = ‘Ryu’, ‘Ryo’ or ‘Ro’ in Japanese phonetic representation. Added to these definitions can also be the historical designations of ‘Ryou’ and ‘Rou’. When used as an ideogram in China, this structure refers to a ‘dragon’ or ‘serpent’, etc. In the Hokkien dialect of Fuzhou, this ideogram can be pronounced as ‘geng’, ‘liang’, ‘ngui’ and ‘liong’ depending upon context and exact location. The idea that this ideogram is pronounced ‘long’ in Fuzhou is incorrect. Correct Historical Sequence: a) ‘Ryu’, ‘Ryo’, ‘Ro’, ‘Ryou’ and ‘Rou’ - b) ‘龍’ (long2) Incorrect Historical Sequence: a) ‘龍’ (long2) - b) ‘Ryu’, ‘Ryo’, ‘Ro’, ‘Ryou’ and ‘Rou’ 3) ‘公’ (gong3) = ‘Ku’, ‘Ko’ or ‘Kou’ in Japanese phonetic representation. When used as a Chinese ideogram refers to something being ‘public’, ‘equitable’ or ‘fair’. In the Hokkien dialect, this ideogram is likely to be pronounced ‘kang’ and ‘kong’ - and not ‘gong’ as usually asserted. Correct Historical Sequence: a) ‘Ku’, ‘Ko’ or ‘Kou’ - b) ‘公’ (gong3) Incorrect Historical Sequence: a) ‘公’ (gong3) - b) ‘Ku’, ‘Ko’ or ‘Kou’ It is impossible for Higaonna Kanryo to have brought back the name of his ethnic Chinese martial arts teacher expressed in a ‘Kanji’ (Japanese) modified script! To assume that he did this is illogical and counter intuitive and yet such an assumption underlies many Western, Okinawan and Japanese attempts at constructing historical narratives that diverge from those advocated by the Mainland Chinese scholars. Interestingly, only in ‘Putonghua’ are the Chinese ideograms ‘劉龍公’ pronounced as ‘Liu Longgong’! In the Hokkien dialect it is more likely that ‘劉龍公’ would be pronounced as ‘Lau Gengkang’ or perhaps ‘Lau Nguihong’, etc, nothing like the ‘Liu Longgong’ contrivance found throughout non-Chinese literature! Therefore, through this application of basic logic it can be proven that ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ historically preceded ‘劉龍公’ - whilst many (if not all) extant Western narratives continuously assert that ‘劉龍公’ historically precedes ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’! Finally, having discussed this matter with a number of ethnic Chinese speakers, it is generally believed that it is unlikely that a person would be named ‘Dragon Public’ (龍公 - Long Gong) as ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ would have been if his Chinese name was written as ‘劉龍公’ or ‘Liu Longgong’. The word order is transposed and the concept highly unlikely as dragons in China are ‘elusive’ i How an Ancient Chinese Martial Art Became a Japanese National and Modern Olympic Sport! (28.12.2018)9/12/2022 If you are someone who likes to keep an eye on all things to do with fighting sports, wrestling, martial arts and the Boxing ring, etc, then you will know the disaster that unfolded when the great Taijiquan ‘Master’ - Leigong (雷公) - was easily defeated by a modern, mixed martial artist in what was billed as a ‘challenge-match’! As this was not a proper or realistic representation of traditional Chinese martial arts, many bona fide gongfu ‘Masters’ were willing to put their reputations on the line to set the record straight! Interestingly, throughout China, Japan and the world, a new wave of Sinophobic discrimination has unfolded – stating that the martial arts produced in China are ‘deficient’, at best ‘second rate’ and possess no real ‘self-defence’ capability! Interestingly, this attitude has been expressed by a number of contemporary Karate-Do Masters living and teaching in Japan who have a very low opinion of Chinese martial arts!

Perhaps a historical fact many of these Japanese Karate-Do Masters do not know is that the fighting system they now call ‘Karate-Do’ was originally a traditional Chinese martial art! The story begins in the Ming Dynasty – which was founded by the emperor ‘Hongwu’ (洪武) whose real name was ‘Zhu Yuanzhang’ (朱元璋). He ruled between 1368-1398 CE – and was a highly skilled martial artist who fought his way from village peasant to the Dragon Throne (overthrowing the ‘foreign’ Yuan Dynasty in the process)! In order to assist the people of ‘Liuqiu’ (琉球) [Ryukyu] with their social construction - Hongwu instructed that the people of Fujian province be chosen as trusted representatives of a) the Ming Dynasty and b) Chinese culture. This was a plan to extract (in its entirety) an already prosperous, highly skilled and economically developed population in China from around the Fuzhou area of Fujian province (comprising of hundreds of men, women and children representing thirty-six distinct name-clans) and reconstructing this entire community in a designated (and previously ‘empty’) geographical area of the ‘Liuqiu’ island (situated near the seaport of Naha City)! The ‘Liuqiu’ people would first refer to this settlement of Chinese people as ‘Tang Ying’ (唐營) or the ‘Tang Encampment’ - but in 1650 CE the name was changed to ‘Tang Rong’ (唐榮) or ‘Tang Glory’! Following the Japanese invasion and annexation of the island, a process which began in 1609 CE with the Satsuma Invasion, and 1879 CE with the Imperial Japanese Army – this place was renamed ‘Kume’ (久米) Village – or the place of the ‘Long Rice’. The thirty-six Fujian families brought shipbuilding and ship-navigating skills, as well as a general and specific knowledge of carpentry, engineering, roadbuilding, housebuilding, farming, animal husbandry, Chinese medicine and Fujian martial arts! The purpose of their relocation was to teach the local ‘Liuqiu’ people every skill and art that they knew to facilitate their development as a distant part of the Chinese cultural milieu. The immediate issue was one of defence regarding the attack of the island by Japanese pirates – or seaborne criminal marauders believed to be based on the Mainland of Japan! At this time, the official attitude of the Japanese government toward China was one of respect and there is no evidence in the 1300s of a covetous attitude toward the ‘Liuqiu’ islands. Indeed, Japanese pirates were considered as a much as a problem to the Japanese themselves, as they were to the Chinese at this time! The Ming Dynasty emperor wanted to establish regular sea lanes operating between the East coast of China and ‘Liuqiu’ - with the ‘Liuqiu’ ships being able to defend themselves from attack and the crew able to fight off any attempts at being boarded! This ‘self-defence’ ability had repercussions regarding the development of militarising the island’s borders and effectively resisting and repelling any attempts at invasion! This was achieved by the Fujian martial arts practitioners studying the indigenous fighting arts of the ‘Liuqiu’ people and combining these techniques with the fighting systems they had brought from the areas surrounding Fuzhou. This fusion of fighting styles generated a new combat system known as ‘Chinese Hand’ (唐手 - Tang Shou) As ‘Tang Hand’ (technically ‘open-hand’) was considered to be very potent and particularly deadly, dangerous and powerful, the learning of this martial art was limited only to dignitaries and certain ‘select’ individuals! To facilitate the learning of ‘Tang Shou’ a special martial arts school was established which only recruited from the island’s ‘warrior’ caste families! Just as China’s political power waned in the subsequent centuries, the power of neighbouring Japan increased. This culminated in the 1879 annexation of the ‘Liuqiu’ island and the changing of its name to ‘Okinawa’. This led to the ruthless suppression of the pro-Chinese ‘Liuqiu’ aristocrats and the outlawing of all Chinese cultural activities! Many ‘Liuqiu’ people who practiced Chinese martial arts fled to China at this time to escape from this Japanese attack upon their culture. It is said that a substantial number of ‘Liuqiu’ martial artists arrived in Fuzhou around this time and settled down studying local Fujian martial arts from established Masters. This meant that the ‘Tang Hand’ that they already knew was augmented by Fujian martial arts styles they now studied closer to the source of authentic Chinese culture. This process of refinement established an even deadlier type of ‘Tang Shou’! One outstanding member of the ‘Liuqiu’ warrior caste who came to Fuzhou around 1879 was one ‘Higaonna Kanryo’ (东恩纳宽量) - a well-known practitioner of ‘Tang Shou’! Higaonna Kanryo was once a ‘Liuqui’ nobleman! After studying ‘Tang Shou’ for three years, he later came to China seeking further advice. Higaonna Kanryo was taken as a disciple by ‘Xie Chongxiang’ (谢崇祥) - a renowned Master of Fujian White Crane Fist (白鹤拳 - Bai He Quan). Higaonna Kanryo studied very diligently under Xie Chongxiang and learned all the technical nuances of the White Crane Fist – integrating this new knowledge into the ‘Tang Hand’ he already knew and eradicating a number of its shortcomings. This process made Higaonna Kanryo a formidable fighter in his own right! Indeed, after Higaonna Kanryo returned to what was now the ‘Okinawan’ area of Japan – he promoted ‘Tang Shou’ wherever he went to great admiration and respect! Due this popularity, Higaonna Kanryo opened a large number of Tang Shou training halls throughout Okinawa! He was assisted in his efforts by his foremost disciples – Miyagi Chojun (宫城长顺) and Mabuni Kenwa (摩文仁贤和) as well as many others. Later, modern Karate-Do (空手道 - Kong Shou Dao) was developed when the disciples of Higaonna Kanryo stratified outward and away from the Chinese influence and integrated their Chinese martial arts with the existing traditional fighting systems of Japan. For instance, the founders of the four major modern Karate-Do styles were all disciples of Higaonna Kanryo! The names of these styles are written in traditional Chinese script – but are pronounced in the Japanese language. These styles are: 1) Goju Ryu (刚柔流 - Gang Rou Liu) - Hard-Soft Lineage 2) Shito Ryu (系东流 - Xi Dong Liu) - literally ‘Itosu-Higaonna Lineage’ - taking the first ideogram from each surname of: a) ‘Itosu Yasutsune’ (系 - Shi) and b) ‘Higaonna Kanryo’ (东 - To) 3) Wado Ryu (和道流 - He Dao Liu) - Harmony-Way Lineage 4) Shotokan Ryu (松涛馆流的 - Song Tao Guan Liu) - Shoto’s House Lineage All the four major styles of modern Karate-Do were all disciples of Higaonna Kanryo – therefore Higaonna Kanryo is the father of modern Japanese Karate-Do – which is premised upon various Chinese martial arts and Okinawan indigenous fighting arts! As this is the case, it is strange that genuine history links modern Japanese Karate-Do to ancient Chinese martial traditions, and yet contemporary Japanese Karate-Do teachers and students are taught to have such a blinkered grasp of the past and a complete disrespect for the present! Of course, it is the same old story that the false belief is put around that only flowery hand and embroidered legs are left in China – but it is interesting that every time a challenge match is offered, accepted and victory attained – it is never reported in these foreign lands! Perhaps it is because reality has no place in the propaganda that has its origins elsewhere and is designed to separate Asian people from one another! Yes – Japanese Karate-Do has become an Olympic Sport – but this is the success of Chinese martial arts in another country! What must not be allowed is for Chinese martial arts to be ridiculed and demeaned by forces unseen – this is a sadness we cannot afford as a nation! https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1621108271570540161&wfr=spider&for=pc 本是中国地方武术,传入日本之后成为日本国拳,如今已成奥运项目 听风听雨听历史 2018-12-28 23:02 如果你是一个喜欢关注拳台,关注搏击的人,那么你一定会知道今年搏击圈的大事情就是中华传统武术太极拳大师雷公被现代格斗选手擂台秒杀,这让当时很多的传统武术大师都有点坐不住了,而这件事情更是再次掀起了传统武术只是花架子的言论浪潮。而不光光是国内,日本也有很多空手道大师十分的看不起中国传统武术。 不过,或许许多日本空手道高手不知道,其实空手道原本是中国的一种传统武术。在明朝朱元璋的洪武年间,朱元璋为了帮助琉球进行社会建设,于是,朱元璋让杜建对口支援,而当时的福建为了建设琉球,不光带去了经济发展,更是还把福建的武术给带了过去,福建的武者,在去到了琉球之后,结合了琉球的一种格斗术,发明了一种新的拳法,这种拳法就是唐手。 因为,这种拳法是琉球新创,于是,在琉球只规定了琉球的达官显赫以及一些武术大家才能够学习,因此,也形成了一种特殊的武术流派琉球武家。因为,中国的逐渐衰弱,1897年的时候,日本吞并了琉球群岛,并且极度打压琉球的达官贵族,也使得琉球武家不复存在,因此,当时绝大一帮学习唐手的琉球武家去到了中国,学习中国的拳法,努力的改良唐手的实战和格斗。 而来到中国求学的那一批唐手武家之中,不得不提东恩纳宽量。东恩纳宽量本是琉球贵族,学习了三年的唐手,后来,随着来到了中国求教,东恩纳宽量拜了一位叫做谢崇祥的福建武术大师学习,而谢崇祥是一位白鹤拳高手,东恩纳宽量跟着谢崇祥学习的日子,极力地学习了白鹤拳中的长处,将它和唐手结合起来,弥补了唐手中的一些不足,也使得东恩纳宽量的武学造诣也有了一个质的飞跃。 在东恩纳宽量的回到了日本之后,他在日本极力地推广唐手。他在冲绳开设了许多的唐手武馆,并且还带出了宫城长顺、摩文仁贤等弟子,后来,在东恩纳宽量的弟子与日本传统武术结合之后,才有了如今的空手道,而空手道中的刚柔流、系东流、和道流和松涛馆流的四大派系的创始人都是东恩纳宽量的弟子,由此可见,东恩纳宽量对于日本空手道的重要意义。 如今,日本空手道已经成为了日本的武道,更成为了日本的国拳,但是,越来越多的日本空手道高手却看不起中国传统武术,觉得中国传统武术早已经失去了实战,只剩下了花拳绣腿。 而如今,空手道还成为了奥运会项目,中国传统武术却越来越衰弱,简直就是一种悲哀! Dear Tony

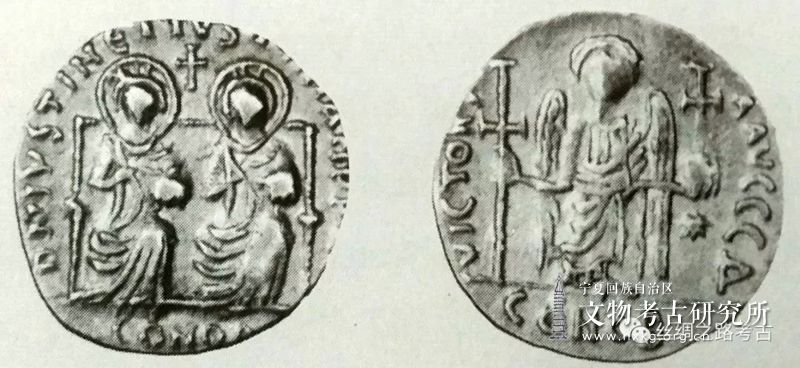

I read the following short extract in a book entitled 'When China Ruled the Seas - The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne (1405-1433)' By Louise Levathes (OUP), 1994, Pages 173-174 - which explains the difference in policy between two emperors with one applying expansion and sharing with no thought to the cost - with the other emperor closing China off from the outside world! In all of this, and following the settlement of the 36 Fujian families to 'Liuqiu' - the 'King' of 'Ryukyu' is mentioned: 'At first the changes were hardly perceptible. Emissaries continued their missions to China's shores. But in 1436, when Nanjing officials repeatedly appealed to the court for more craftsman, their request was summarily denied. Concerned about the burden on the people, Zhu Zhanji's successor halted construction in shipyards and urged frugal economic practices. In 1437, after paying tribute, the King of Ryukyu Island (south of Japan) asked the emperor for new court costumes, which had been given to his envoys since the beginning of the dynasty. The ones he had, he said, had "become old." And who knew when he would be able to return to China? The seas were now "dangerous and difficult." The emperor, however, declined to grant the King's request. The following year, the Siamese mission to the court was robbed of its cargo of pearls, gold, and jade by two dishonest officials in Guangdong. Through no fault of his own, the Siamese ambassador arrived in court without tribute. Such behaviour from local officials would have been impossible to imagine in the Yongle reign. That same year, the emperor sent a message to the King of Java saying that the "envoy" he had sent was wild and drunk and had caused the deaths of several people, including himself. "You should be more careful," the emperor commanded, "in choosing envoys in the future."' I have copy-typed this for your records. Indeed, the author worked at the time for National Geographic (c. 1990) and had carried-out a great deal of her research in China - using Chinese language sources. (I believe the John Hopkins Center for Chinese and American Studies at Nanjing University in Jiangsu province, is very popular and respected amongst Chinese people). Interestingly, and rather disappointedly, this is the only 'Ryukyu' reference in her entire book! Thanks Adrian Historical Contextualisation: How 4th Century CE Roman Coins Found Their Way to Okinawa! (7.9.2022)9/9/2022 The earliest Western mention of ‘China’ (as ‘Seres’ - Greek for ‘Land of Silk’) seems to be in the 4th century BCE work of the Greek physician and historian ‘Ctesias’ (Κτησίας) of Cnidus (now in Turkey) who was born c. 416 BCE. This is described in the 2008 Chinese language book entitled ‘中国与罗马 - Zhong Guo Yu Luoma) or ‘China and Rome’ written by the esteemed Mainland Chinese academic Qui Jin (丘进). In a book of anecdotes describing the inhabited regions of the world, Ctesias is quoted as saying, ‘The people of Seres and North India are said to be strong and tall in stature! It is said that some can grow as tall as 13 cubits! (a single ‘Coudee’ or ‘Cubit’ = approximately 0.5m). It is not uncommon for these people to live for 200 years!’ ‘赛里斯人和北印度人身材高大,甚至可以发现某些身高达13肘尺(Coudée,约合0.5米)的人。他们可以寿逾200岁。’ The modern science of archaeology – when applied around the world - tends to support the idea that both China and the Greek and Roman worlds possessed vague and hazy ideas regarding one another’s existence certainly during the early centuries BCE. We are on firmer ground during the year 97 CE, when it is recorded that the Eastern Han Dynasty of China attempted to send an emissary - named ‘Gan Ying’ (甘英) - to Rome but that his journey was blocked by the Parthians. Han Dynasty records further state that the Roman emperors Antoninus Pius (86-161 CE) and Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE) both sent envoys from Rome to China. In the case of the latter, the Roman emissary reached China in 166 CE – landing at a place called ‘Rinan’ (日南) County before being escorted to Louyang! The Han Dynasty and the Roman Empire, however, conducted commercial trade prior to making direct political contact from around the 1st century CE (through third parties and middlemen, etc) using the maritime and land-based Silk Roads. The Han Dynasty exported fine silk to Rome, whilst the Romans exported glassware and equally high-quality clothing fabrics to the Han Dynasty. This early history is relevant when considering the interesting historical finds announced in the Japanese press during 2016! Around September 26th, 2016, The Japan Times (and many other publications) broadcast the story that Japanese archaeologists had been conducting exploratory excavations (since 2013) within the grounds of the ruined Katsuren Castle in Okinawa (which had existed between the 12th-15th centuries CE) located near Uruma City. On this day, however, things were a little different as Japanese archaeologist - Toshio Tsukamoto it was announced - had discovered four badly worn copper coins (measuring between 1.6 and 2 cm in diameter) thought to have been minted at in ancient Rome at some point during the 4th century CE. Hiroki Miyagi, an archaeologist at Okinawa International University, explained: "Katsuren Castle belonged to the Ryukyu Kingdom during the 14th and 15th centuries and was the only channel for trade between Japan and China. At that time, East Asian merchants mainly used Chinese ‘square-hole’ (方孔 - Fang Kong) money as currency, and Western currency was unknown in this part of the world. If Roman-era coins were circulating in Japan, it is speculated that this ancient currency may have flowed into the Ryukyu Kingdom from China or Southeast Asia.” It was also reported that one 17th century CE Ottoman Empire coin had been discovered during the ‘dig’, together with five other metallic objects also thought to be coins. Of course, what Hiroki Miyagi falls to mention is that when these coins were thought to have been deposited on the island - ‘Okinawa’ (or more properly ‘Liuqiu’) was part of China and not part of Japan! It was only from 1609 onwards following the Satsuma invasion that ‘Liuqiu’ became nominally a part of Japan – whilst its three Kings continued to send tribute to the Chinese emperor out of respect. It was only with the 1879 ‘annexation’ of ‘Liuqiu’ (and the surrounding islands) by the Imperial Japanese Army that ‘Liuqiu’ was renamed ‘Okinawa’ and the island chain it is a part of became known as ‘Ryukyu’ (the Japanese pronunciation of ‘Liuqiu’). When did ‘Liuqui’ become a distant part of the Chinese empire and when was this small island integrated into the umbrella that it is Chinese culture? Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) records mention contact with an island referred to as ‘Liuqiuguo’ (流求國) - or the ‘Flow Attract’ Country (perhaps suggesting a country the tides of the South China Sea will take you toward quite naturally). This is recorded in the: a) ‘Sui Dynasty Historical Records’ (隋書 - Sui Shu) – with the relevant data entered as follows: b) Volume 81 - ‘Eastern Barbarian – List of Histories and Descriptions’ (東夷列傳 - Dong Yi Lie Chuan) c) Chapter 29 - ‘Chen Ling Biography’ (陳稜傳 - Chen Ling Chuan) c) Chapter 46 - ‘Flow Attract Country History and Description’ (流求國傳 - Liu Qiu Guo Chuan) d) Chapter 64 - ‘List of Histories and Descriptions’ (列傳 - Lie Chuan) This history records (and details) the Sui emperor ‘Yang’ (煬) [569-618 CE] who reigned 604-618 CE – and his mounting of a successful seaborne expedition to attack and conquer the distant island known as ‘Liuqiu’. Liuqiu (pronounced ‘Ryukyu’ in the Okinawan and Japanese languages) lies around 500 miles due East of the coast of Fujian province. This was not an act of wanton aggression upon the part of the Chinese State – but rather a policing action whereby Chinese villains and rebels had fled China and were carrying out pirate activities and other disruptive endeavours. Although some scholars have tried to suggest these records are discussing the island of Taiwan, the academic consensus is that Taiwan is far too big and far too close to Mainland China to serve as a safe haven for fleeing Chinese bandits, and is so close to the Chinese Mainland, that it does not fit the description of the difficulties the Chinese fleet had locating and navigating its way to the island of ‘Luiqiu’! Furthermore, no one in Taiwan had heard of the Chinese descriptive term of ‘Liuqiu’ - whereas in Okinawa the local people have referred to their island as ‘Ryukyu’ (‘Liuqiu’) for centuries! The Sui Dynasty Historical Record States: 1) 607 CE - During the second month of the third year of the reign of emperor Yang (607 CE) – the Cavalry Commander Zhu Kuan (朱寬) was ordered to travel eastward to visit and make contact with the people of ‘Liuqiu’! Due to the language barrier, however, all that was achieved was the kidnapping of one local person who was forcibly returned to China! 2) 608 CE - During the fourth year of the reign of emperor Yang (608 CE) - Cavalry Commander Zhu Kuan was ordered to lead a military expedition and invade the ‘Liuqiu’ island – but he refused to obey the order and instead ‘returned his cloth armour’! 3) 610 CE - During the sixth year of the reign of emperor Yang (610 CE) – a very large seaborne military expedition (consisting of 10,000 soldiers) was launched from Mainland China – led by General ‘Chen Ling’ (陳稜) and Senior Minister ‘Zhang Zhenzhou’ (張鎮州) - which was successful in traversing the rough seas, finding and landing on ‘Liuqiu’ island – where the local forces were met in combat and defeated! Thousands of men and women were captured and returned to Mainland China. 4) It is said that this third militarised seaborne expedition was the consequence of Chinese rebels that had: a) Defied and opposed the Sui Dynasty emperor before fleeing to ‘Liuqiu’, before b) Being pursued, confronted, apprehended and finally returned to the Mainland China to face trial. The Chinese name ‘Liuqiu’ was used during the Tang and Song Dynasties (referring to the Ryukyu Islands) and was even retained during the Islamic Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368 CE). Although ‘Liuqiu’ (流求) was retained as a place defined as being under the influence of the Chinese cultural umbrella – the Yuan Dynasty - however, altered the spelling of the name to the similar sounding ‘琉求’ (Liuqiu). This changed the usage of the traditional first ideogram of ‘流’ (liu2) [meaning ‘flow’ or ‘tradition’] and replaced it with the new ideogram of ‘琉’ (liu2) [which means ‘precious’]. This was only a very slight change – adding the beautifying particle ‘⺩’ (yu4) meaning ‘jade’ to the left-hand side of the ideogram – a typical Islamic gesture of respect and good will. Despite this recognition, the treacherous seas separating Mainland China from ‘Liuqiu’ meant that communication was spasmodic. Even though Japanese envoys routinely visited China – it was clear that the ‘Ryukyu’ Island were not considered part of Japan by the Japanese themselves - certainly not prior to the 17th century. All of this background information is required if the 2016 discovery of Roman coins on the island of Okinawa is to be properly contextualised and understood. During 1372 CE, the Ming emperor ‘Taizu’ (太祖) sent his envoy – Yang Zai (楊載) - to ‘Liuqiu’ to formalise diplomatic relations. King Zhongshan (中山 ) of the Ryukyu Islands agreed that a regular ‘Tribute’ (貢 - Gong) should be paid to the Chinese Court in exchange for military protection, political affiliation and cultural exchange (all favouring the Ryukyu people). A major problem hindering this arrangement was a) the distance of around 500 miles one way, and b) the unpredictable and terrible weather and rough seas! The Chinese Court attempted to solve this issue in 1392 CE by despatching the so-called thirty-six families (or ‘name clans’) from various areas of Fujian province to be resettled on the ‘Liuqiu’ island. This probably amounted to hundreds of men, women and children who were settled at a place termed ‘Kume Village’ or the ‘Chinese Village’. These people were chosen for their skills in growing, harvesting and sustaining forests (for producing wood), ship designing and ship building, as well as ship navigators and pilots! The purpose of this relocation was to establish efficient, open and permanent sea-lanes between ‘Liuqiu’ and Mainland China (mainly with the adjacent Fujian coast). With these people came many other important arts and crafts – including house building, animal husbandry, Chinese medicine, farming and various forms of Fujian martial arts. Of course, Chinese martial arts had been deployed on ‘Liuqiu’ since 607 CE, and it is thought a general transmission of these arts were made to the island from that time onward. As ‘Liuqiu’ people were considered ‘Chinese’ in the political sense, then in all likelihood it is plausible to assume that Mainland Chinese soldiers stationed on ‘Liuqiu’, and Chinese migrants living in ‘Liuqiu’ were willing to teach their martial arts to individuals outside of their immediate families (probably more so in the case of soldiers). From 1392 CE onwards, however, the Chinese settlers on ‘Liuqiu’ were acting under orders to relay as much Chinese cultural knowledge as possible to the local ‘Liuqiu’ people. This arrangement existed for 217 years without interruption until the Japanese ‘Satsuma’ invasion of the ‘Ryukyu’ Islands in 1609 CE! There was intense military resistance from the local ‘Chinese’ and indigenous ‘Liuqiu’ people – but being so far from Mainland China (and so close to Mainland Japan) the local inhabitants were eventually defeated. This development led to a dual influence operating on on ‘Liuqiu’ which involved the local population still voluntarily sending tribute to China – whilst nominally acknowledging a political association with Japan. This situation persisted for another 270 years before the modern soldiers of Imperial Japan invaded and annexed ‘Ryukyu’ - renaming the island ‘Okinawa’ and ‘banning’ any and all ‘Chinese’ cultural influence! From 1879 onwards the ‘new’ history of Okinawa sought to downplay, negate and expunge the extensive cultural input China exercised over the development of ‘Liuqiu’! This poat-1879 negative attitude toward China is very different to the respect and deference once shown by many Japanese people from the Sui Dynasty onwards, including the 13th century Japanese Zen Buddhist monk known as ‘Dogen’ [道元 - Dao Yuan] (1200-1253) - as recorded in his magnus Opus entitled the ‘Shobogenzo’ (正法眼蔵 - Zheng Fa Yan Cang) - which records his travels to China and respectfully represents the Chinese cultural education he received, valued and preserved! What this suggests is that a) ‘Liuqiu’ was not considered part of Japan until the late 19th century despite an unconvincing Satsuma claim in the 17th century – which was half-hearted at best – and b) neither ‘Liuqiu’ nor Japan were part of any known ancient pathway or trade route which would have linked these areas with 4th century CE Rome! At least not officially, although accidental shipwrecks cannot be totally ruled out. This is important as many of the 2016 news stories edge toward the idea that ‘Okinawa’ (as an active and prominent part of ancient Japan) was part of a ‘hidden’ or otherwise ‘obscure’ ancient trade route that neither ‘Rome’ (nor any other major participant) bothered to name or record in their otherwise extensively kept trade histories! In other words, there is no known or recorded ancient trade route which linked Japan (much less ‘Liuqiu’) to 4th century Rome! The earliest mention of what is thought to be ‘Liuqiu’ (Ryukyu) is in 607 CE, although there is some debate about whether this might refer to the island of Taiwan. If this is not ‘Liuqiu’ (Ryukyu) then it is not until 1372 CE (during the Ming Dynasty) that ‘Liuqiu’ (Ryukyu) is mentioned. This is 765 years later and would imply that ‘Liuqiu’ (Ryukyu) remained obscure and isolated for far longer than first thought! To add another layer of uncertainty to this issue, it is also true that toward the end of the Ming Dynasty, The Northern part of Taiwan was known as ‘Xiao Liuqiu’ (小琉求) or ‘Small Liuqiu’ with what is today known as ‘Okinawa’ being referred to as ‘Da Liuqiu’ (大琉求) or ‘Great Liuqiu)! Even so, the balance of probabilities suggest that the 607 CE (and after) encounters strongly suggest that the current Okinawa was the location of the Chinese seaborne expeditions, particularly when it is considered that the island nation itself possessed ‘three Kings’ - a point of historical fact certainly not attributable to Taiwan! If the date ‘607 CE’ is the time that ‘Liuqiu’ (Ryukyu) enters the history books, then this is 270 years after the death of the Roman emperor – Constantine I (272-337) - also known as ‘Constantine the Great’. When all this information is considered, what were these Roman-era coins doing in the foundations of a ruined ‘Liuqiu’ castle? The thirty-six families that relocated in ‘Liuqiu’ from Fujian province must have resulted in hundreds of people suddenly arriving on the island and establishing a settlement from 1392 CE onwards. Perhaps Roman coins had found their way to Fujian province (the gateway to China for centuries) and had become symbols of good luck to be placed in prominent places. Japanese language sources state that the four Roman-era coins were discovered within the 14th and 15th century layers of the ruined foundations of Katsuren Castle – which was destroyed in 1458 CE during internecine fighting. These layers of excavation coincide with the arrival of highly skilled Fujian migrants from the Mainland of China. I suspect these 2016 Roman coin finds were deliberately dropped into the foundation of Katsuren Castle by the Fujian Chinese migrants (for good luck) when they were helping to build and/or repair the structure (as there is a disagreement within Japanese academia as to exactly ‘when’ the castle was ‘built’ and started ‘functioning’)! The point I am making is that ‘Liuqui’ was part of China during this part of its history and so these Roman-era coins, regardless of how they arrived in ‘Liuqiu’, were in a remote part of ‘China’ and not an external ‘Prefecture’ of Japan. Between 1897-2000 CE, forty-six (Byzantine) Eastern Roman Empire (330-1453 CE) coins were discovered in China (mostly in old tombs but occasionally already held in museums or as artefacts under private ownership). To date, there has now been over fifty (ancient) Roman coins discovered throughout China, all mostly gold and belonging to the earlier Byzantine Roman period (these gold coins begin to appear in a significant number during the 6th century CE, with copper and Sassanid silver preceding). A few examples of the finds of Roman coinage in China include: a) 1895: At the end of the Qing Dynasty, Westerners obtained sixteen Roman copper coins in Lingshi County, Huozhou, Shanxi Province, which were cast from the time of the Roman emperor Tiberius (42 BCE–37 CE) to emperor Antoninus Pius (86-161 CE). Technically speaking, these finds cover the periods of the ‘Roman Republic’ (509-27 BCE) and the ‘Roman Empire’ (27BCE-395 CE). b) 1953: It is ironic that ‘Liuqiu’ first enters the written history books during the Sui Dynasty of China, as in 1953 Chinese archaeologists unearthed a gold ‘Justin II’ (d. 578) Roman-era coin, minted during the early (Byzantine) Eastern Roman Empire (330-1453 CE) period and discovered in the Sui Dynasty tomb of ‘Dugu Luo’ (獨孤羅) [534-599]! This tomb was situated in a small village of ‘Dizhangwan’, near the city of Xianyang in Shaanxi province. c) 1961: A replica gold coin featuring the image of the Eastern Roman Emperor Heraclius I (575-641 CE) was discovered within a Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) tomb located in Tumen Village in the Xi'an (Chang’an) area of Shaanxi province. d) 1977: Whilst excavating the Eastern Wei Dynasty (534-550 CE) tomb of the Official ‘Li Xizong’ (李希宗) [501-540] situated in the Zanhuang County area of Hebei - a Roman coin featuring the portrait of ‘Theodosius II’ (401-450 CE) was discovered - an emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire! e) 1977: The same dig at the Tang Dynasty tomb site in the Zanhuang County area of Hebei – there were discovered two gold coins featuring the co-rulers of emperor ‘Justin I’ (450-527 CE) and his ‘nephew’ (Justinian) - who would eventually become emperor ‘Justinian I’ (482-565 CE). f) 1978: At a dig in the Ci County area of Hebei province, a Roman gold coin was found in the tomb of Princess ‘Linhe’ (邻和) [538-550 CE] of the Eastern Wei Dynasty (534-550 CE). This Roman coin dated to the reign of emperor Anastasius I Dicorus (431-518 CE) of the Eastern Roman Empire! The coin is 17.6 mm in diameter, 0.54 mm thick, and weighs 3.1 grams. g) 1998: During early June in the Guyuan County area of Ningxia (near Gansu province), a Roman coin dated to the reign of emperor Anastasius I Dicorus (431-518 CE) of the Eastern Roman Empire was found on farmland! The coin is 17.6 mm in diameter, 0.54 mm thick, and weighs 3.1 grams and was discovered alongside fragments of a yellow-glazed porcelain flat pot. h) 2000: A farmer from Anbian (安边) Town was out tending his fields in Dingbian County, Shaanxi province, when he discovered an early Eastern Roman Empire (330-1453 CE) gold coin that had been welded onto a metal ring. The date and Roman emperor could not be discerned due to the corroded state of the artefact. The copper coins discovered in Okinawa in 2016 are very badly worn and difficult to read, but it is believed they belong to ‘Constantine I’ (227-337 CE) and he ruled over the ‘unified’ Roman Empire (27BCE-395 CE). My view is that Fujian province, as a gateway into China, probably experienced a wealth of foreign goods, artefacts and many different types of currency. I suspect the hundreds of people who comprised the thirty-six Fujian clans of China carried with them tons of equipment, weapons, tools and all sorts of everyday and cultural objects – as well as various forms of paraphernalia – to build a new life on the island of ‘Liuqiu’ from 1392 CE onwards. Although Kasturen Castle on Okinawa is sometimes reported as existing between the 12th-15th century, there is still much debate about the exact date within Japanese archaeology, with many experts stating that the castle only existed between the 13th or 14th centuries before being destroyed in 1458 CE. One possibility missing in all these narratives is that the local Chinese population, many of whom were experts in construction of one sort or another, participated in the planning, designing, constructing and maintaining of Kasturen Castle. If this did happen, then I would suggest that a number of ‘foreign’ copper coins were placed in the foundation when the castle was being built, rebuilt or extended, etc, by the local Fujian (Chinese) population who were following a common practice back in their home country! Archaeology demonstrates that these ‘foreign’ coins were believed to possess some type of magical value in the afterlife whilst being placed in the tombs of the nobility, whilst ordinary Chinese people thought of these coins as objects of ‘feng shui’ (風水) or ‘wind’ and ‘water’ significance in the maintaining and augmenting of the natural flow of energy throughout the environment. What better way of ensuring the ‘safety’ and ‘strength’ of a fortified building than giving it a semi-magical ‘boost’ in the fulfilment of its defensive design capabilities. It is entirely plausible that ever since Roman envoys started landing on the coast of China during the 2nd century CE - it was Fujian province they were making first contact with, and it is through this interactive capacity that a number of Roman coins bearing the portrait and Latin mottoes of ‘Constantine I’ came into the possession of ordinary Fujian people. By latter generations laying these Roman coins in the foundations of Kasturen Castle – they were fulfilling part of their imperial duties which involved educating the ‘Liuqiu’ inhabitants in ALL aspects of Chinese arts and sciences – with ‘feng shui’ (geomancy) being viewed as being very important at the time – certainly as important as the ability to build seaworthy ships, fight properly or to understand and apply Chinese medical knowledge correctly! Chinese Language Sources: Japanese Language Sources: English Language Sources:

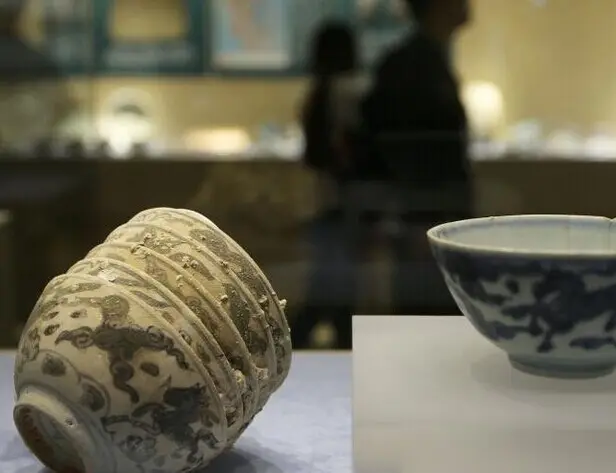

South China Sea Shipwrecks and the Brave 19th Century Journey of Higaonna Kanryo! (6.8.2022)9/6/2022 The Maritime Silk Road linked Southern China to vast areas of the known world for over two-thousand years (since at least the Qin and Han Dynasty times (3rd century BCE)! During that time, the ancient leaders of China established seaborne links with other civilisations that sparked, trade, tribute and cultural exchanges. As the seas around South China are unpredictable, changeable and can be highly dangerous, perhaps one in every ten ships that set out from China ladened with artefacts and treasure sunk to the bottom of the sea – with a similar statistic covering ships heading to China from foreign lands! What this means is that a rich archaeological record exists on the sea floor spread all around the South China coast and surrounding coast! It is a record cultural triumph and natural disaster! Humanity’s creativity tempered by nature’s crushing hand! A great deal of the porcelain and pottery discovered on the seafloor originated in Fujian province – the area that many people visited from overseas to make contact with Chinese culture and learn intangible cultural crafts such as the martial arts! This was an exportation of another kind of Chinese creativity stored in the minds and bodies of those who learned the arts after daring to cross the dangerous seas! Fujian province became a hub for foreign visitors to China as the various Dynastic rulers limited foreign intrusion into China to initially just this area. On occasion, should a visitor require access to the hinterland of China, permission might eventually be given, but such incidences were rare until Western cannons literally smashed their way out of this cultural enclave – and others such as the docks and warehouses that had been established around the Southern coastal areas during the 19th century! Even so, for other Asian visitors such as Higaonna Kanryo (1853-1915) who made the journey from Ryukyu (Okinawa) around 1867, the old convention still applied, and his journeying was limited to Fujian province! He studied various types of ‘Southern Fist’ (南拳 - Nan Quan) which included Fujian ‘White Crane Fist’ (白鹤拳 - Bai He Quan) and probably ‘Arahant Fist’ (十八羅漢拳 - Shi Ba Luo Han Quan). This stems from the 1989 announcement by Lin Weigong (林伟功) – an expert in Mainland China regarding the culture of Fujian province - that Higaonna Kanryo’s main martial arts teacher was thought to have been ‘Xie Chongxiang’ [谢崇祥] [1852-1930). Higaonna Kanryo travelled around 500 miles by boat from the Ryukyu Islands in 1867 – and then repeated this journey back away from China in 1881! He covered around 1000 miles of seafaring and managed to survive this journey both, despite the difficulties regarding the unpredictable weather and rough seas! Under the seas that he traversed were thousands of years of cultural artefacts – including the bones of countless people from virtually every country on earth! Chinese Language Source: English Languish Source:

|

AuthorShifu Adrian Chan-Wyles (b. 1967) - Lineage (Generational) Inheritor of the Ch'an Dao Hakka Gongfu System. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed