These bamboo slips from the Western Han Dynasty (202 BC-25 AD) were unearthed in a cluster of tombs in Tianhui Town, Chengdu, the provincial capital, in 2012. Further study on the slips showed that the relics document valuable medical literature belonging to the school that Bian Que once followed.

During the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Period (770-221 BC), Bian Que (扁鹊) drew on the experience of his predecessors and put forward the four diagnostic methods -- inspection, auscultation and olfaction, inquiry, and palpation, laying the foundation for traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) diagnosis and treatment.

Among all the unearthed by archaeologists so far, the content is believed to be a set of ancient medical documents detailing China's hitherto richest content, most complete theoretical system, and of the utmost theoretical and clinical value.

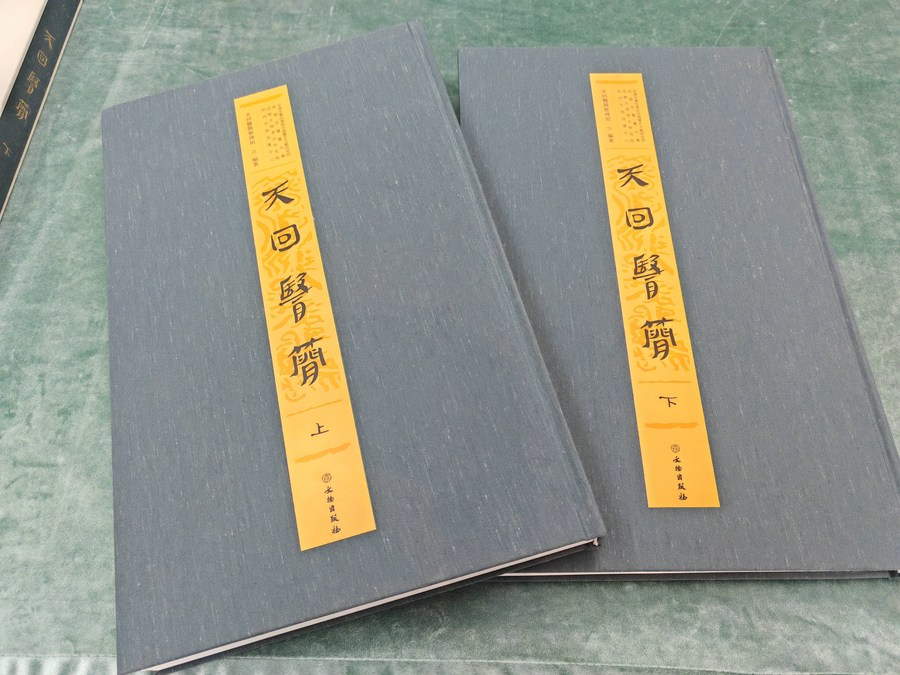

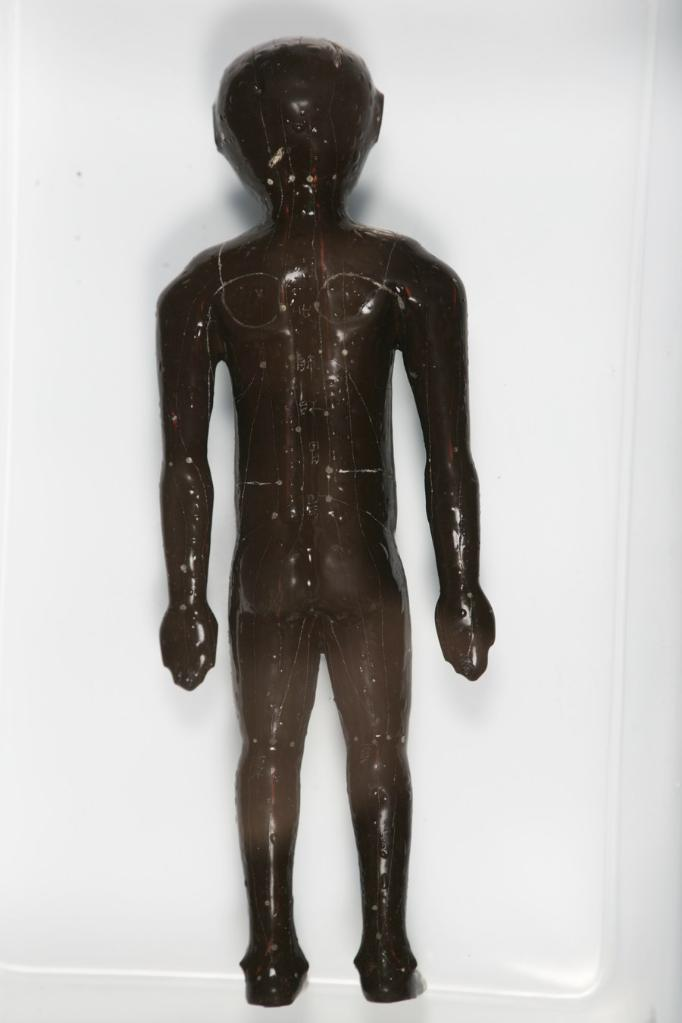

The documents have been compiled into eight medical books as a series of books named "Tianhui medical slips," said the information office of the Sichuan provincial government during a press conference held on Thursday. All the materials, including images of the bamboo slips, editorial explanatory notes, and illustrations on the TCM meridian mannequin uncovered alongside the slips, are contained in the newly published books.

"Many prescriptions recorded on the slips are still relevant today for common disease treatment. We hope to advance China's TCM theoretical innovations, improve the TCM clinical efficacy, and make more people learn about TCM culture through systematically studying the slips," said Liu Changhua, chief editor of the series.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed