Kumite - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate)

取 - 捕 (to) = take hold of, gather, control, arrest

り(ri) = logic, reason, understanding

取 (qu3) = take hold, fetch, receive, obtain and select

り- 理 (li4) = put into order, tidy up, manage, reason, logic and rule

Left Particle = 𤔔 (luan4) means to 'govern' and 'control' - and is structured as follows:

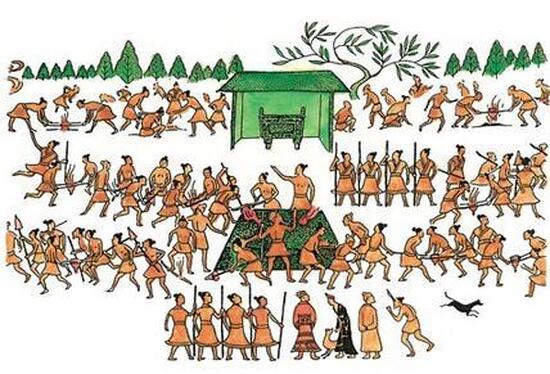

The literal meaning of '亂' (luan4) [or 'Ran' in 'Ran-dori] - is that it refers to a lack of skilful organising ability (disorder and confusion). The thin silk threads are not placed correctly on the wooden frame (loom) - and therefore cannot be 'weaved' together in an orderly fashion. This entire process lacks the required profound knowledge and experience to achieve the objective - thus the hands (and body) cannot be used in the appropriate manner.

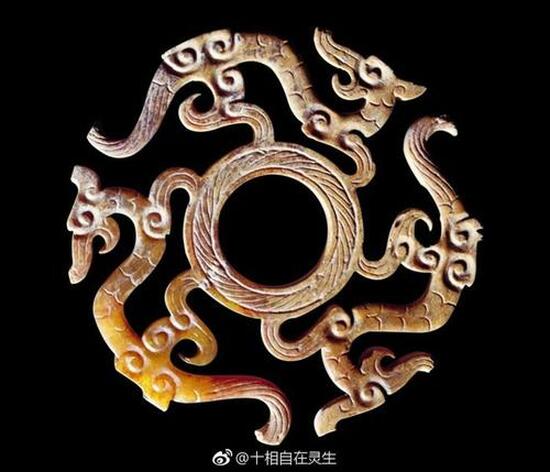

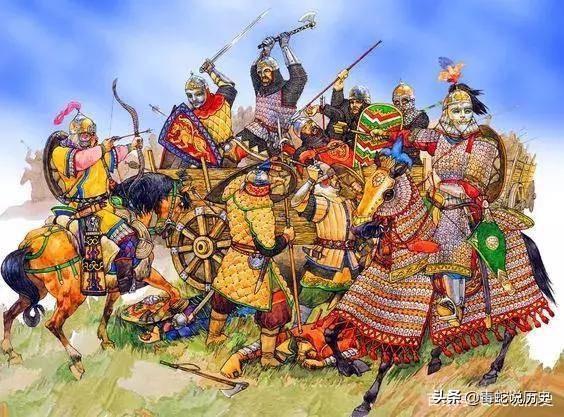

Ran-Dori (乱捕り), as a complete process, suggests that it is the opposite of the above 'lack of skill' that is require in sparring. Not only is this skill required, but 'ri' (li) element (理 - li3) - suggests a 'regulation' and an 'administration' (premised upon logic and reason) - such as the profound skill required to 'cut' and 'polish' jade.

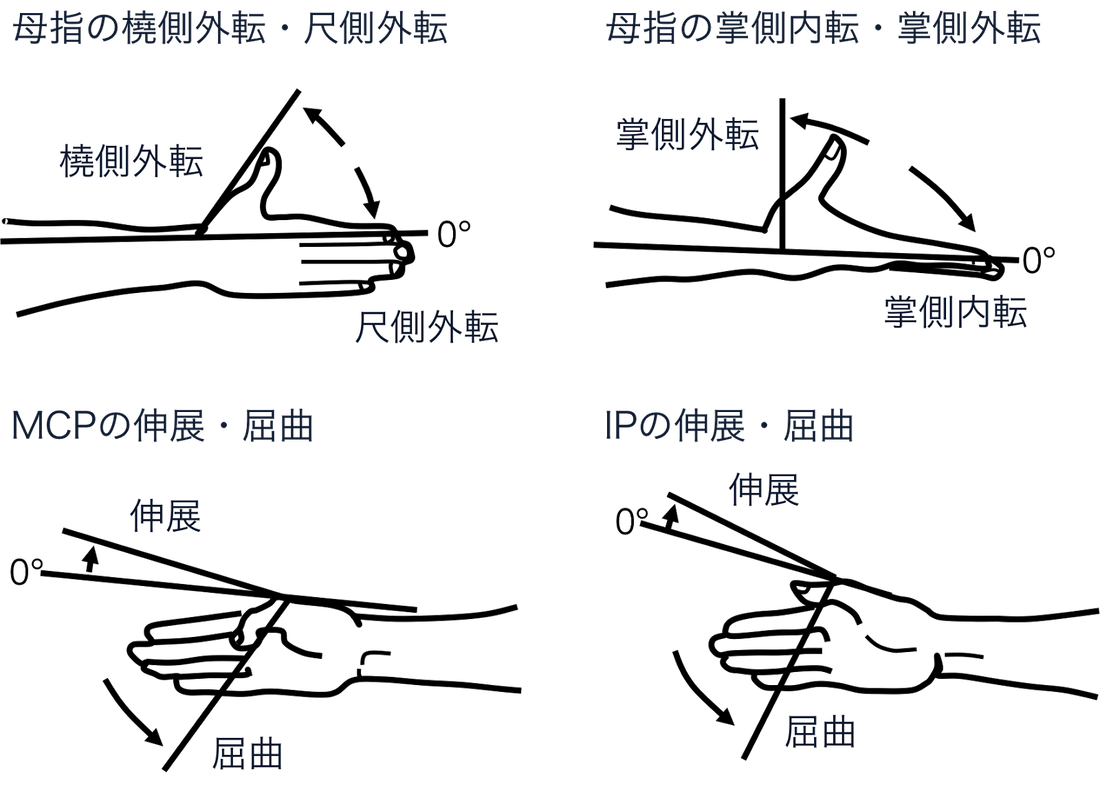

'Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. '

I was curious as to why the two hands were so specific in their orientation and my colleague said that they are clearly carrying out the process required for ancient 'weaving'. One hand is laying the 'warp' - or 'vertical' thread down through the loom - whilst the other right hand is performing the function of 'weaving' multiple 'weft' threads into place horizontally across the loom!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed