|

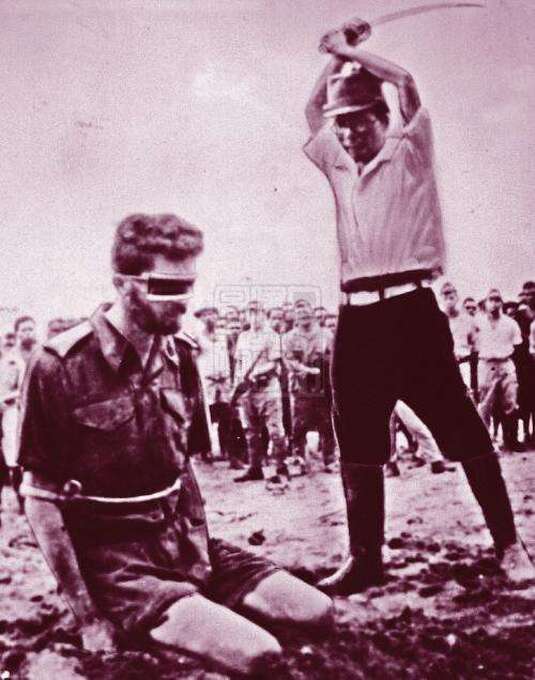

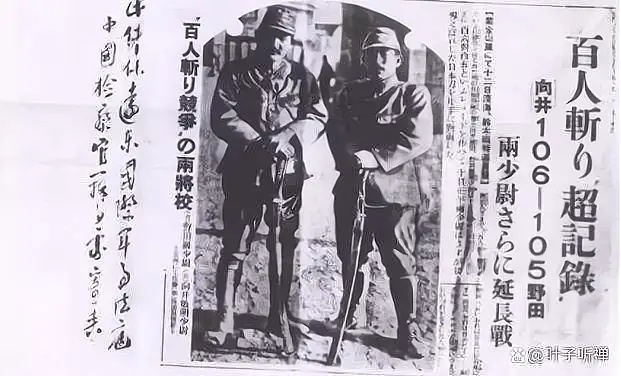

Within the Movie ‘Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence’ a Japanese POW Camp Commandant decides that the prison population of European (military) inmates are ‘spiritually lazy’. When being beaten or made to stand for hours in the sun had not altered this situation, the Japanese Officer decided that the Camp population would undergo the Shinto ritual of ‘Misogi’ (禊) – in this instance – involving a 24-hour fast-period of no eating or drinking. This is despite the daily ration being intolerably low to start with. Most prisoners – even the stronger men – were on the brink of starvation. The Japanese Officer (Captain Yanoi) – by further depleting the starvation rations - would also adhere to this ritual of ‘fasting’ whilst traditionally dressed - and sat in meditation in the Camp ‘Dojo’. This is the pristine training hall used by the Japanese Officers for martial arts and spiritual practice (a mixture of Buddhist and Shinto spiritual traditions). Similarly, in the book ‘Empire of the Sun’ written by JG Ballard – the (civilian) POW Camp (Assistant) Commandant (Sergeant Nagata) occasionally orders Chinese vagrants (often women and girls) to be ‘beaten to death’ by Japanese soldiers wielding wooden clubs. The actual 'Commandant' - Hyashi - was in fact a 'civilian' and a careerist diplomat who tended to only interfere in Camp daily activities if absolutely necessary. Obviously, Hyashi never interfered in Nagata's brutality. These starving Chinese people sit patiently outside the POW Camp waiting to see if they will be allowed in to receive a portion of the already meagre rations. The women and girls are often raped by the Japanese guards before the Camp populace of British people are assembled to watch the unfolding ritual of ‘despatch’. Sergeant Nagata believes the British POWs are ‘spiritually lazy’ and seeks to stimulate their individual (and collective) ‘ki’ (氣) flow. This ‘life force’ not only flows through each individual body – but also through the entire Camp. As Sergeant Nagata believes the Chinese people to be an ‘inferior race’ – their brutal murder (achieved through a demonstration of ‘Japanese’ manly vigour) – will ‘release’ the ‘ki’ from their (broken) bodies and supplement that available throughout the Camp. The two primary Shinto rituals on display in both of the above examples are: 禊 (Misogi) – Purification (Cleansing) of the inside and outside of the mind and body. 祓 (Harae) – Purification (Exorcism) of corruption out of the interior of the mind and body. As this ‘Kanji’ is in fact comprised of ‘Chinese’ ideograms, I can read these characters and give some type of explanation as to what these rituals are supposed to represent – at least in a historical context. I say this as the rubric of Japanese ‘spiritual’ fascism distorted (for decades) rituals and practices that would normally not have been so severe or murderously brutal. Bear in mind that within ten-years of WWII being over – Western students of Judo, Kendo and Karate-Do were avidly volunteering to undergo these rituals – albeit in a non-war setting. Nevertheless, the rituals that the Imperial Japanese used to torture and murder millions of Western and Asian people – are today routinely considered part and parcel of a legitimate Japanese martial arts practice. On the face of it, this is an extraordinary rehabilitation. As Chinese ideograms, these ‘Kanji’ characters can be read as follows: a) 禊 (xi4) is comprised of an upper and lower particle: Upper Particle = 气 (qi4) – refers to ‘energy’, ‘breath’ and ‘vital force’ Lower Particle = 米 (mi3) – denotes husked ‘rice’ that needs to be ‘cooked’ (transformed) in water Therefore, 禊 (xi4) suggests that the process of cooking rice in a cauldron (by lighting a fire underneath and boiling the water) not only produces nutritious food (which sustains all physical life) but also generates ‘steam’ as a useful and yet crucial by-product. This steam - through the (hidden) ‘pressure’ created - ‘lifts’ the lid of the cauldron with an effortless ease. It is this ‘unseen’ influence of a physical process that drives this concept. b) 祓 (fu4) is comprised of of a left and a right particle: Left Particle = 礻(shi4) is a contraction of ‘示’ (which denotes an ‘altar’ and the ‘rituals’ associated with it) – and refers to structured acts of ‘instruction’, that require ‘attention’ and possess great ‘importance’. Lower Particle = 犮 (ba2) denotes a ‘dog’ (犬 – quan3) that is ‘running’ (丿- pie3). The implied meaning is to perform a dramatic task with the appropriate amount of effort and required energy. This suggests that a religious ritual must be correctly performed (as if in a temple or at an altar) in the physical world - that opens a connecting door-way to the spiritual world. Once this channel has been correctly opened – the influence of the spiritual world is then allowed to positively flow (unseen) into the material world – thus influencing temporal events. Correct (disciplined) and timely action in the physical world is the basis of this concept. Success is defined as achieving an exact ritualistic replication that does not deviation from the accepted norm – as ‘deviation’ of any sort is tantamount to ‘ill-discipline’. Conclusion Armed with this knowledge, it can be suggested that the Japanese concept of ‘禊’ (Misogi) refers to arduous physical activity that requires ‘sweating’. Through hard and continuous labour – a definite and positive metamorphosis is produced in the material world – that possesses definite (but ‘hidden’) implications for the inner world (almost as a side effect). By way of comparison, ‘祓’ (Harae) refers to a metaphysical ritual that although partly physical in its ritualistic content, remains nevertheless ‘metaphysical’ in nature and intent. This is because ‘祓’ (Harae) constitutes a ‘purifying’ spell achieved through words, actions, and a specific and certain state of mind.

0 Comments

Dear Tony Interesting. Thank you for your knowledgeable explanation of sparring - an adult 'tiger playing with a cub'. This inspired me to research 'Ran-Dori' in Japanese-language sources - which is written as '乱取り' - '乱捕り' and 'らん‐どり'. Both of the following Japanese-language Wiki-entries (I have checked the data is correct) should be read side by side to gain an all-round clarity - as the 'Randori' entry does not specifically mention Karate-Do - whilst the 'Kumite' page explains that in some Styles of Karate-Do - 'Kumite' is referred to as 'Randori'. Randori - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate) Kumite - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate) I suspect the inference is that in Okinawan Karate-Do the term 'Randori' is used - whilst in Mainland Japan - the term 'Kumite' is the preferred. Difficult to say, but as you know, 'nuance' and 'implication' is an important part of Japanese communication. What is NOT said is as important (sometimes more so) than what IS said. Perhaps this Yin-Yang observation is just as important for sparring - whatever its origination and purpose. As for the traditional Japanese and Chinese ideograms - this is what we have: 乱取りand 乱捕り 乱 (ran) = chaos, disorder 取 - 捕 (to) = take hold of, gather, control, arrest り(ri) = logic, reason, understanding Therefore, 'Ran-Tori' and 'Ran-Dori' are synonymous - with the concept expressed in its written form as '乱-取り' - ot 'Chaos (Random Movement) - Seize Control of'. What is 'chaotic' in the environment is wilfully taken control of - by imposing an outside order upon it. This suggests that the 'non-controlled' is 'controlled' by the structure of Kata-technique - which is brought to bear by an expert. There also seems to be the suggestion that that which 'moves' - is wilfully brought to 'stillness'. As for a Chinese-language counter-part, perhaps we have: 乱 - 亂 (luan4) = disorderly, unstable, unrest, confused and wild (Japanese = 'turbulent') 取 (qu3) = take hold, fetch, receive, obtain and select り- 理 (li4) = put into order, tidy up, manage, reason, logic and rule It would seem that the Japanese term of 'Ran-Dori' equates to the Chinese term of 'Luan-Quli' - or 'Disorder - (into) Order Rule'. Your reply inspired me to think about what the Japanese '乱' (Ran) - or Chinese equivalent '亂' (luan4) - actually means. What is the definition of the 'disorder' being referenced to when 'Ran-Dori' is being discussed? Therefore, '亂' (luan4) is comprised of a 'left' and 'right' particle: Left Particle = 𤔔 (luan4) means to 'govern' and 'control' - and is structured as follows: a) Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. b) Lower (Inner) Element = 幺 (yao1) - a contraction of '糸' (mi4) which refers to 'thin silk threads'. c) Lower (Outer) Element = 冂 (jiong1) this is a 'comb', 'beater' or 'heddle' - a device to 'order' the silken threads that require weaving. In normal usage, this ideogram denotes the structured boundary that clearly demarks the city limits. Right Particle =乚 (yi3) is a contraction of '隱' (yin3) - meaning to 'hide', 'conceal' or 'cover-up', etc, as in 'something is missing'. It can also refer to a required process that is 'profound', 'subtle' and 'delicate' - but which is currently 'lacking'. It may also mean 'secret' and 'inward' or 'inner', etc. I would say that 'obscuration' is what this ideogram refers to in its meaning. Conclusion The literal meaning of '亂' (luan4) [or 'Ran' in 'Ran-dori] - is that it refers to a lack of skilful organising ability (disorder and confusion). The thin silk threads are not placed correctly on the wooden frame (loom) - and therefore cannot be 'weaved' together in an orderly fashion. This entire process lacks the required profound knowledge and experience to achieve the objective - thus the hands (and body) cannot be used in the appropriate manner. Ran-Dori (乱捕り), as a complete process, suggests that it is the opposite of the above 'lack of skill' that is require in sparring. Not only is this skill required, but 'ri' (li) element (理 - li3) - suggests a 'regulation' and an 'administration' (premised upon logic and reason) - such as the profound skill required to 'cut' and 'polish' jade. I was discussing Randori with another language expert and they gave me more data which I have added to this paragraph: 'Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. ' I was curious as to why the two hands were so specific in their orientation and my colleague said that they are clearly carrying out the process required for ancient 'weaving'. One hand is laying the 'warp' - or 'vertical' thread down through the loom - whilst the other right hand is performing the function of 'weaving' multiple 'weft' threads into place horizontally across the loom! As a matter of comparison - the 'Kumi' (組) in Kumi-te (組手) - Chinese 'Zu Shou' - means to 'weave continuously'. This translates as 'to be skilful' (the silken threads are skilfully woven [糹-si1] together forever - like the longevity of a sacrificial vessel [且 - qie3] - which are traditionally made out of stone). Therefore, Kumi-te literally refers to a 'continuous skill that unfolds through the hand'. This may be compared to the term 'Ran-Dori' which refers to a 'missing skill' that has yet to be 'acquired' and is in the midst of 'being acquired' (through developmental training) - whilst Kumi-te implies that the required skill is already present and should manifest automatically.

Etymology of ‘Gedan Barai’ (下段払い) - or ‘Gedan Hara-I’ Dissecting the ‘Lower Block' of Karate-Do!3/8/2023 I was asked a while ago to look into the etymology of the Karate-Do self-defence technique of 'Gedan Barai' - once by a British student (who had attended an advanced Japanese language course as he is a Solicitor) - and again by a Japanese student who was passing through the UK and had visited a few Dojos - saying some 'sounds' of the names of the techniques being used did not seem correct: My view is that this transmission of culture is a) ongoing (and therefore a continuous process), and b) is a two-way street which must involve forgiveness and understanding. We must all help one another until our mutual understanding is correct. What is interesting is how philosophically different the 'Lower Block' is treated within Karate-Do compared to the 'Middle' and 'Upper' Blocks (which are explained merely as mechanical devices and not associated with the 'Conception Vessel' they pass through)! It is as if the 'Lower Block' is from a very old martial ritual! Finally, I was once told that the 'Lower Block' is not just a 'parry' or 'check' of an incoming attack - but is also a simultaneous 'Hammer-Strike' to the opponent's groin-area. Interesting food for thought.

Dear T

With regard to 'Muchimi' (ムチミ) - 'heaviness', 'rooted': When I was younger (and less experienced in translation), I probably would have been tempted to read the Japanese (Katakana) character of 'チ' (chi) - or 'one thousand' - as being related to the Chinese ideogram of '手' (shou3) - meaning 'open hand' (and to 'clutch', etc), as they look very similar in structure. My instinct would have led me in this direction considering the martial arts usage related with the term 'Muchimi' - applying a logical 'reverse chain of events', so-to-speak (in other words - 'working backwards' using logical association). However, all the multi-language dictionaries I have access to today - strongly suggest there is no connection between these two characters. As this possible association played on my mind (in the sense that no stone should remain unturned), I checked '手' (shou3) in these dictionaries (focusing on the 'Japanese' variants) and found that even today - the Chinese ideogram of '手' is still often used - 'unchanged' - within Japanese script, usually rendered as 'te' or 'shu', etc. When '手' is modified within Japanese script - it is presented as 'テ' (Katakana) and 'て' (Hiragana) - pronounced 'te' and 'shu' respectively. Therefore, although the 'チ' (Katakana) character found within 'Muchimi' (meaning 'one thousand') is 'similar' to the (Katakana) character 'テ' (te) - meaning 'open hand' - as you can see, there are slightly different upper structural differences - despite a certain lower level similarity. After further studying the history of each of these specific Japanese (Katakana) characters - the lower similarity appears to be purely coincidental rather than deliberate. The conclusion being that there is no connection between the 'チ' (Chi) - one thousand -Japanese (Katakana) character and the '手' (shou3) - meaning 'open hand' - Chinese ideogram. Best Wishes Adrian I have written elsewhere about the Chinese (martial) cultural concept of ‘凌空劲’ (Ling Kong Jin) often erroneously translated in English as ‘Empty Force’ (and subsequently misinterpreted) - but what follows is a list of similar concepts. These all encapsulate the idea of striking an opponent ‘at a distance’ - without making physical contact (as is required in Western Boxing or Mixed Martial Arts, etc). 1) 隔山打牛 (Ge Shan Da Niu) = Smashing Mountains Striking Oxen 2) 隔空打人 (Ge Kong Jin Ren) = Smashing Empty Power (into) Opponents 3) 印掌 (Yin Zhang) = Imprinting Palm 4) 百步神拳 (Bai Bu Shan Quan) = Hundred Step Spirit Fist 5) 透劲 (Tou Jin) = Penetrating Power 6) 棉花掌 (Mian Hua Zhang) = Cotton Flower Palm As these concepts are misunderstood both in China and outside of China, it goes without saying that they are much maligned. (Number '6' actually involves striking and breaking bricks - experiencing the impact as something like 'hitting cotton' - although many also consider this to be a 'fake' skill similar to 'hitting at a distance'). Part of the problem involves the exploitation of these concepts for monetary profit by those who possess no real idea about what these concepts mean. When these frauds are exposed (usually during a sparring match) - the logic employed suggests that the concepts these people are peddling are as corrupt as the personality that is misrepresenting them! This is incorrect – but as there is no separation between the defrauding element and the legitimate martial concept itself – no debate can be developed when the baby is being thrown-out with the bath water! Obviously, ss someone who firmly rejects capitalism (and the liars it produces) I am certainly NOT supporting any variation of these frauds. I also make no secret of my opposition to the Eurocentric racism prevalent in the West that is routinely aimed at Chinese (and all ‘Asian’) people and their culture. When confronting this type of ignorance, there are a lot of components to unpack. I am not going to waste my time ‘arguing’ with racists – as I would rather confront these morons before they can do any real damage to my family and/or community. As for the genuine people – do not be deceived by charlatans (of any type) and always look beyond the horizon for better and more complete knowledge! Do not fooled by misrepresentations of Chinese (martial) culture. Chinese Language Source:

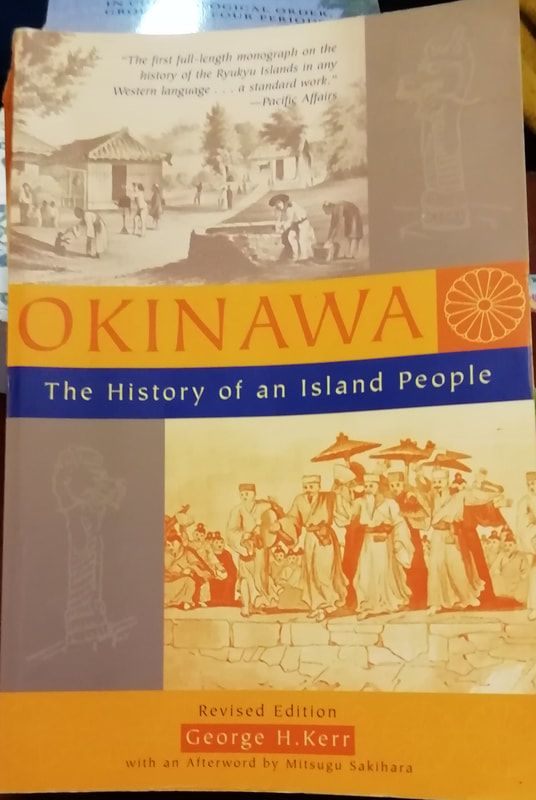

Karate is mentioned just once, and even then, more or less in haste, and certainty not in any historical depth! This is disappointing from a book comprising of over 550 pages! Professor Mitsugu Sakihara provides a fascinating 'Afterword' and about ten-pages of corrections, deletions and other necessary 'errata' clarifications. Again, with a ground-breaking book of such historical scope and ambition - this type of 'correction' by an Asian academic fully armed with the latest research is nothing to be ashamed of - as a vast majority of the historical wealth presented within this books stands up to Japanese and Okinawan academic scrutiny! Of course, we must all be careful to correctly discern 'fact' from 'fiction', 'truth' from 'myth' and 'lies' from 'truth'! I present this data to add the over-all research into the fascinating history of Okinawan Karate-Do - much of which originates in Southern China, indigenous Okinawan martial culture and it would seem - the fighting arts of South-East Asia (Thailand, Myanmar and Cambodia, etc) or even Indo-China (Vietnam)! George Kerr's research into the origin of Karate-Do is not referenced (so we do not know where he acquired his information) - but he is of the opinion that 'Karate' was brought back to the Ryukyu Islands by Ryukyu sailors visiting (and training in the martial arts of) South-East Asia and/or Vietnam - and not China! I have heard a similar idea expressed in some Japanese and Chinese language articles - but only in as much as suggesting 'some' Karate-Do techniques (such as the 'round-house' kick) originated within the martial culture of South-East Asia - but not the complete system! Whatever the case, to consider all the available data - the data must be made available to all - and freedom of thought will do the rest!

GLOBALink | Sports Geography: Henan in the Transmission of Chinese Martial Arts! (30.9.2022)9/30/2022 Twenty-five-year-old Li Yinggang is a Coach at Shaolin Tagou Martial Arts School in Songshan, Central China's Henan province! He started martial arts practise at the age of 9 and shifted to free combat 3 years later. Students Practice During a Martial Arts Class Under the Instructions of Coach Li Yinggang at the Shaolin Tagou Martial Arts School in Songshan, Central China's Henan Province - July 6, 2022. (Xinhua/Wu Gang) Since he was 16 years old, Li has been taking part in the Professional Free Combat Competitions - always winning domestic and international title events several times - including two Golden Belts from the Chinese National Free Combat League! As Li Yinggang says - practicing traditional martial arts has helped tremendously in improving his free combat skills!

Nowadays, Li aims to impart his understanding and experience of traditional martial arts to students during his classes - hoping they can master the essence of martial arts - and inherit and develop Chinese martial arts! Miyagi Chojun (1888-1953) – the founder of Goju Ryu Karate-Do - was born in Naha City on April 25th, 1888. The Miyagi family was of the ‘noble’ (ancient ‘Ryukyu’) class and was very wealthy due to supplying Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) to the Ryukyu Royal Family. This meant that the Miyagi family members were travelling continuously backwards and forwards to imperial China – and possessed continuous ‘official’ clearance from a) the Okinawan Authorities, b) the Japanese Authorities and c) the Chinese Authorities. For most ordinary people this bureaucracy was almost impossible to navigate – and even if navigated successfully – it usually applied to only a ‘single’ return journey! It was this established trade routes between the Ryukyu Island and Imperial China that Miyagi Chojun would use to facilitate his travelling to Mainland China (which might well give credence to his 1915, 1916 and 1936 visits – with ‘1916’ often being the most disputed visitation). The Miyagi family were known locally as a ‘White Silk Seal’ (素封 - Su Feng) - or very wealthy - family. This is written in the Japanese script as そほうか’ - and refers to a family with large land holdings and substantial wealth assets. Miyagi Chojun’s father was named ‘Miyagi Chosho’ (宫城長祥) - who was the third of three sons born in his generation of the Miyagi family. Unfortunately, Miyagi Chosho died early on – and when Miyagi Chojun was three years old (during 1891) he was adopted by relatives from the primary branch of the Miyagi family (which possessed no male heir). Therefore, from an early age, Miyagi Chojun became the official heir – legally designated to inherit the entire Miyagi family fortune! According to biographical details supplied by Aragaki Ryuko [新垣隆功] (1875–1961) - the mother of Miyagi Chojun took him to a neighbour to begin martial arts training when he was eleven years old (during 1899). When Mr Aragaki Ryuko recalled his earliest memories of a young Mr Miyagi Chojun - he described him as an active and competitive child who often caused trouble with other children! Aragaki Ryuko, however, also recognised that Miyagi Chojun was also very talented when it came to fighting! Furthermore, although young, he exhibited a very serious attitude when training in martial arts and retained a sense of utmost discipline! Even when tired – he would never give-up and would always continue to try and move correctly and without error! Aragaki Ryuko carefully observed the behaviour of Miyagi Chojun for three-years to ensure that what he was seeing was correct. Only after this period of character-testing did Aragaki Ryuko stake his own reputation on recommending Miyagi Chojun for training with Master Higaonna Kanryo (1853-1915)! When Higaonna Kanryo accepted this youth as his ‘disciple’ - Miyagi Chojun was aged fourteen-years-old (during 1902). This means that Miyagi Chojun trained with Higaonna Kanryo between 1902-1915. This equals to thirteen-years – with two-years (1910-1912) taken-out for Miyagi Chojun’s military service in the Imperial Japanese Army (in Kyushu). Higaonna Kanryo was very strict and demanded very high levels of self-discipline and commitment from his students! He trained his students so severely that the purpose was to make those with weak characters ‘choose’ to quit training because they found it ‘too difficult’. Higaonna Kanryo would say that everything they needed was provided for their training right outside their front doors – and that they did not have to travel, seek out or attempt to communicate or negotiate! If, after all this pampering they were still unable to commit themselves to serious training – what good were they? Higaonna Kanryo would continuously advise students to go home and take-up a less demanding pastime! He wanted to see if they possessed the courage to come back the next day and face his wraith for them daring to defy his instruction! Miyagi Chojun kept returning and setting himself the daily task of using all the provided body-conditioning equipment surrounding Higaonna Kanryo’s home – whilst showing ‘respect’ NEVER giving in to the provocation to give-up! The more intense Higaonna Kanryo’s pressure became – the ‘calmer’ Miyagi Chojun’s mind would become and the ‘better’ his martial technique would manifest! This impressed Master Higaonna Kanryo – who said his teachers in China were just as hard upon him as he was upon his own students in Okinawa. As a consequence, Miyagi Chojun developed a very powerful (and ‘rooted’ to the ground) martial technique so that he was able to strike with considerable force through a ‘hardened’ and ‘toughened’ body structure that could be ‘relaxed’ inbetween bouts of required ‘tension’! Furthermore, when required, his body could absorb, deflect and redirect all incoming power from the blows of others! Chinese Language Source: 宫城长顺先生生平介绍(转载) 剛柔流实际的创立人是宫城长顺先生(1888-1953)。宫城长顺先生生于1888年4月25日,於那霸市出生。宫城家是以进口中国药材供应琉球王府御用的经商家族,琉球时代上等位阶士族的后裔,在那霸闻名的素封家 (そほうか,指拥有大土地,大資産的家族),宫城长顺先生的父亲是宫城家三男宫城長祥,早亡,三岁时宫城长顺先生被属于无亲子的亲戚领养并且从小被指定为宫城家业的继承人,家道富裕。

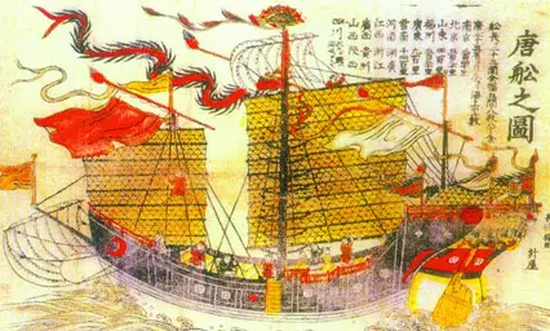

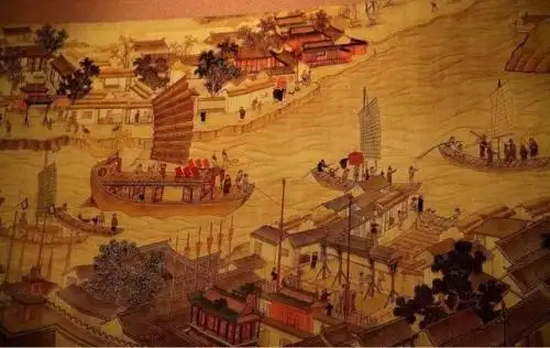

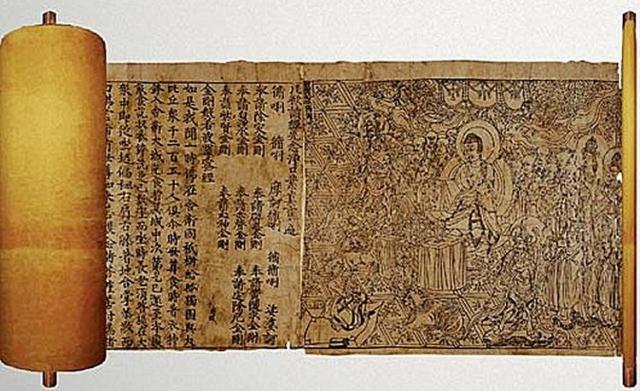

宫城长顺先生11岁开始由母亲带他到其邻居泊手师父新垣隆功先生(1875-1961)门下习武。(新垣隆功先生便是国际冲绳刚柔流空手道连盟IOGKF范士新垣修一先生的祖父,而且新垣隆功先生是位曾经在公开比武中打赢了本部朝基的冲绳空手名人)。新垣隆功先生回顾起年幼的宫城长顺先生时,描述他是个好动并且好胜的孩子,时常与其他孩童闹事。但新垣隆功先生见宫城长顺先生天资过人,习武认真,3年后,即宫城长顺先生14岁那年推荐他到东恩纳宽量先生门下习武。在东恩纳宽量先生极度严格的训练下,宫城长顺先生的性格逐渐变得稳重谦恭。 学生时期的宫城长顺先生每日下课后便跑步十几公里到达其师父之住处训练。并且他将沿途各种大小的石头当成举重或者击打的训练器具。据老一代的前辈描述,宫城长顺先生在学校里体育方面表现出色,特别是体操单杠运动的好手,他也曾经是学校中的柔道好手,但因为出手过重而最后校方要求他退出柔道训练。宫城长顺先生年轻时在也经常参加冲绳的摔跤赛事,但出手重并且经常使用些摔跤之外的技艺最后导致其他摔跤手不欢迎他参与赛事。因他养父临终前劝他别为了摔跤与他人结仇,宫城长顺先生放弃了摔跤。 作者:猫爷习 https://www.bilibili.com/read/cv1652712/ 出处:bilibili Author’s Note: I am of the opinion that the Chinese language term ‘Tang Shou’ (唐手) or ‘Tang Hand’ refers to the totality of the perfected cultural production that was the Tang Dynasty of ancient China! As such, the term ‘Tang Shou’ (唐手) does not – and was never intended – to refer to a school (or system) of Chinese martial arts! In other words, the product being received (Chinese martial arts) - became confused (and conflated) with the culturally defined transmission process (Chinese treasure fleets)! The fact that this confusion has entered into Western discourse as such, represents an error in historical interpretation that must be ironed-out if the genuine history of Karate-Do is to be ascertained. The Karate-Do of Okinawa (and Japan) possesses ‘many histories’ and this article intends to clarify and rectify a problem with historical interpretation relating to perhaps the ‘first transmission’ of Chinese martial arts to the Ryukyu Islands. This process was probably enhanced by the fact the Japanese government sent at least fifteen cultural missions of its own to Tang Dynasty China between 630-894 CE! Until evidence suggests otherwise, I am of the opinion that the earliest martial transmission occurred between the 7th and 10th centuries CE, and comprised of Chinese envoys travelling to Ryukyu and teaching the inhabitants, and various Japanese citizens visiting China, learning whatever martial arts were available and bringing this body of knowledge back to Japan! . Whether any of this initial transmission survives in the diverse modern-day Karate-Do (or Okinawan ‘Te’) techniques (or ‘Kata’) is a matter of interesting conjecture. My personal belief is that it does. As for the meaning of the Chinese ideogram ‘唐’ (tang2) - it is comprised of the following components: Upper Particle = 广 (guang3) - broad, wide, extensive and vast. Middle Particle = 肀 (yu4) - to write with a brush. Lower Particle = 口 (kou3) - to speak, announce and to order. This would suggest that the Tang (唐) Dynasty defined itself through its intention (and ability) to develop, maintain, preserve, spread and share what its exponents believed to be its vastly superior culture! The Tang Dynasty possessed the ability to grow vast forests, harvest the wood in a sustainable manner, build vast armadas of ships, staff those ships with hundreds of suitably trained and qualified people and then fill the holds of these ships with all kinds of cultural treasures intended to enrich and inspire the people living in all the discoverable areas outside of the geographical China! I think this interpretation supports my idea that ‘Tang Shou’ (唐手) does not represent the name of a particular style of Chinese martial arts, but rather is a collective term encompassing all the cultural crafts, artifacts and abilities that the skilled people of the Tang Dynasty could produce! ACW (28.8.2022) Chinese language historical encyclopaedias record a number of diplomatic missions between Tang Dynasty China and the Ryukyu Islands – with the Ryukyu Kingdom being a considered as a tributary State of China (alongside ‘Kyushu’ and other places). As part of these missions, Chinese Envoys conveyed various types of armed and unarmed martial arts to the people of the Ryukyu and Kyushu Islands as a ‘gift’ from the emperor of China (records also discuss similar missions to ‘Honshu’ or the Japanese Mainland as in those days the Japanese Authorities encouraged interaction between its own citizens and Chinese people – encouraging as much learning of Chinese culture as was possible). The Chinese martial arts conveyed were part of the general Chinese missions which were known as ‘Chinese Hand’ (唐手 - Tang Shou) - a term used to refer to the spread of a broad array of Chinese culture. Overtime, the term ‘Chinese Hand’ (唐手 - Tang Shou) lost the meaning pertaining to the act of spreading a general body of Chinese cultural information – and came instead to be associated only with the one element of that transmission – namely the ‘martial’. In other words, in and of itself, ‘Chinese Hand’ (唐手 - Tang Shou) should not (and does not) refer to the practice of Chinese martial arts – even though it has become synonymous with the historical analysis of the Okinawan and Japanese martial art now known today as ‘Karate-Do’. The cultures of Kyushu and Ryukyu already possessed their own indigenous martial arts traditions (distinct from those found in China or Mainland Japan) during the time of the Tang Dynasty. These local fighting traditions began the process of ‘integrating’ with (and slowly transforming) the transmitted Chinese martial arts – often developing and changing the original structure and purpose. As these Chinese martial arts arrived as part of a greater cultural gift transmitted by the Tang Dynasty – this explains why these diverse fighting systems became known by the general name of ‘Tang Shou’ (唐手) - with ‘Tang’ (唐) being used to denote ‘China’ in general, but also the ‘ruling’ Dynasty during which time the transmission is believed to have occurred! If the martial art referred to was transmitted during the Song (宋), Yuan (元), Ming (明) or even Qing (清) eras – then logic dictates that the fighting systems in question would have been named after those Dynasties! This thinking holds true, even if these Chinese martial arts were part of much broader Chinese cultural exchanges! Another point to consider is the use of the ideogram ‘手’ (shou3) - literally denoting an ‘open’ hand (with four fingers and thumb being present) - which in and of itself does not represent anything particularly ‘martial’ within Chinese fighting culture! Indeed, when combined with the ideogram ‘高’ (gao1) - as in ‘高手’ (Gao Shou) - the concept of ‘expert master’ is formed! This is someone who possesses a ‘greater perception’ because they have attained a ‘higher point of view’ and are able to ‘act’ in the physical world by using their ‘hands’ (and by logical implication - the rest of their body) to perform a superior type of transformative labour, which progressively alters the human world! Therefore, whereas ‘高手’ (Gao Shou) implies an exceptional (individual) being who possesses the ability to transform the world through the use of their superior action (in whatever form) – when the term ‘Tang Shou’ (唐手) is used, I believe it refers to the culture of the ‘Tang Dynasty’ in general, elements of which were exported out of the geographical boundaries of what we would now term ‘China’ - as part of various diplomatic missions to other parts of the world (effectively spreading Confucian spiritual and material culture). Chinese martial arts may well have comprised part of these so-called ‘civilising’ gifts – but the martial arts themselves would not have originally been termed ‘Tang Shou’ (唐手) - but held this title only in the sense of being transmitted as a ‘gift’. The Chinese diplomatic mission would have been termed ‘Tang Shou’ (唐手) - comprising of thousands of different aspects of Chinese culture – with martial arts representing just one aspect. In general, a physical art designed for martial purposes would be designated within Chinese cultural parlance by the term ‘拳’ (quan2). To understand why this ideogram denotes a ‘closed’ or ‘clenched’ fist, its structure must be examined in greater detail. At the start, it is important to understand that the ideogram ‘拳’ does contain the ideogram ‘手’ (shou3) - but only as a modified particle, the reasons for which I shall now explain. The ideogram ‘拳’ (quan2) is comprised of the following constituent parts: Top Particle (Phonetic) = ‘龹’ which is a contraction of ‘𢍏’ (juan4) - to roll rice into a ball. Lower Particle (Compound) = ‘手’ (shou3) - an open hand with four fingers and a thumb. The key to transforming ‘an open-hand to a closed-hand' lies in the inherent meaning of the upper particle ‘𢍏’ (juan4): Top Particle = 釆 (bian4) - sorting rice, distinguishing and discriminating. Lower Particle = 廾 (gong3) - two hands pushing outward, bowing in salute and to surround and encircle. We may then state that ‘拳’ (quan2) a hand is ‘closed’ or ‘clenched’ (although not necessarily with ‘force’), so that rice may be mixed, separated and rolled into balls. A hand maybe ‘closed’ but at the same time it possesses a tremendous skill which differentiates between every action that must be carried-out and performed! At the highest level of martial arts mastery, the ‘closed’ hand remains ‘relaxed’ even when ‘closed’ - as the bone structure is held perfectly aligned without undue effort – so that bodyweight can be effortless transmitted without hindrance through it and into the opponent. The bodyweight of the opponent can also be ‘borrowed’ temporarily by allowing it to enter the aligned bone structure before ‘ejecting’ it out of the fist with tremendous penetrative force! If the Tang Dynasty Authorities intended for the martial arts to be named after themselves (which I doubt), then they would have used a term such as ‘Tang Quan’ (唐拳) - or ‘Tang Fist’. More to the point, when emperors and officials did develop systems of martial arts – they usually gave it their own personal names! Dear Tony

The academic problem with this type of article - is that it is discussing a Chinese martial culture transported to Okinawa (which was a tributary State of China until 1879) - and yet possesses no Chinese language references. (Chinese martial arts do not originate in America or Japan). It is US and Japanese trends in their own respective academic traditions - reinforcing (without any Chinese input) their own ideas about China (regardless of whether any of the knowledge claims are 'true' or 'false'). The single 'Chinese' reference comes from a Chinese-American (JM Yang) - who could not prove any of his lineage claims in China, etc. A good example that breaks through this type of thinking in the West (and Japan) is Brian Victoria's 'Zen At War' (an uncomfortable read for many). Brian Victoria is an Australian who lives in Japan - and yet can read, write and speak the Japanese language. He explains how many post-WWII Japanese 'Zen' and 'martial' heroes in the West where well-known 'War Criminals' in Japan - with DT Suzuki serving as just one example. The translation work of Thomas and JC Cleary also often exposes the US-Japanese lie which falsely suggests Chinese Buddhism 'died-out' in China and is only now preserved within Japan! Master Xu Yun (1840-1959) had much to say on the Japanese behaviour abroad being motivated by their 'Nationalism' and a lack of basic Buddhist and Confucian morality - even thought 'Shinto' (Shen Dao) - in its Chinese original form - could possibly be a type of 'Daoist' nature worship! |

AuthorShifu Adrian Chan-Wyles (b. 1967) - Lineage (Generational) Inheritor of the Ch'an Dao Hakka Gongfu System. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed