|

Wikipedia is a wealth of sagely advice – much of it misleading, incomplete and out of context. For instance, the author dealing with the ‘Tai Sabaki’ page - states that the usual interpretation of Tai Sabali in the West which involving ‘evasion’ is ‘wrong’. However, if an individual can ‘read’ Chinese and/or Japanese ideograms – it is obvious that whatever this concept is - ‘evasion’ forms a central aspect of it. The author in question does not fully comprehend the entire concept of Tai Sabaki and is attempting to join the two ends of an idea together whilst omitting a (vast) theoretical centre-ground! 1) 体 (Tai) - Japanese Equivalent of Chinese ideogram ‘體’ (ti3) = ‘body’ This is related to a body (comprised of - and structured by - its internal bone structure) which is augmented in the physical world through musical rituals (involving drumming) and the adornment of jade of jewellery. The body is enhanced by the placement and alignment of its inner structure and the means (rituals) through which this body traverses the outer world. That which is ‘detrimental’ is avoided and that which is ‘nourishing’ is embraced. There is an implication in the Japanese language that ‘体’ (Tai) refers primarily to the trunk and the abdomen – and only secondarily to the limbs. It is the ‘centre’ of the body which has priority over the ‘periphery’ of the body. 2) 捌 (Saba) - Japanese Equivalent of Chinese ideogram ‘捌’ (ba1) = Disentangle This ideogram - (in its Chinese interpretation) can mean ‘eight’ - an alternative form of ‘八’ (ba1). A ‘hand’ which expertly uses a ‘knife’ - cuts through the flesh and bones of a fish so that it is separated into ‘eight’ clean parts (probably a generic term meaning ‘many’). There is also the central idea of ‘disentanglement’ - so that no unnecessary error (or resistance) is met. This is because ‘entanglement’ means ‘hindrance’ - and the skill referred to here involves the ‘avoidance’ of such self-imposed difficulty. Evading ‘resistance’ is the correct path that leads to such a skill. The blade of the knife skilfully feels its way around (and along) the natural contours of the bones – and does NOT cut directly (at right-angles) into the bone-structure at any time. There is a ‘going with’ rather than a ‘going against’. This ideogram is the central element of this Karate-Do principle - and probably means slightly different things within the various styles which make use of it. 3) き(Ki) - Japanese Equivalent of Chinese ideogram ‘幾’ (ji3) = Skill There is an indication of ‘quantity’, ‘measurement’ and ‘refinement’ within Japanese language dictionaries. The suggestion is that the correct manipulation of exact amounts is a great skill which has to be mastered in any successful avenue of life. This idea spans both the material and the spiritual world! An individual can carefully follow the established criterion laid down by those who have gone before – or if such an individual possesses the correct (and right) amounts of psychological insight and physical strength – then they might set out on their own path and become an inspiration for those who are to come! Conclusion: Meaning When taken as an integrated whole – the martial principle of Tai Sabaki (体捌き) suggests that the physical body (its central core and not just its periphery) is skilfully used (manipulated) in a combat situation so that there is no direct conflict between the defender deploying this technique - and an attacker ignoring this technique. Tai Sabaki (体捌き) is NOT just the skilful movement of the arms and legs in ‘protection’ of the central core (the torso). Tai Sabaki (体捌き) is a ‘centre-out’ technique that requires the core and periphery to work in concord. Strength does not clash with strength. The ability to assertively ‘give-way' is the key to this technique. Indeed, when the timing is perfect - ‘giving-way’ becomes far stronger than the momentary strength associated with a dramatic (but short-lived) show of strength! Giving-way, at its highest manifestation, not only ‘absorbs’ and ‘nullifies’ ALL incoming power – but when performed correctly, generates the basis for ‘greater’ power to be produced that is not reliant upon linear (muscular) strength – but rather the ‘circular’ movement associated with the structures of the bones and joints! The bodyweight ‘drops’ into the ground through the shaft of the (aligned) bones and rebounds upwards through the centre of the bone-marrow – producing a seemingly endless supply of ‘muscle-free’ power! As this power is greater than that associated with the muscular ‘tension’ of thuggery – the defender occupies a unique time-space frequency within which the attacker cannot access (or penetrate) regardless of the willpower exhibited. The linear attacks cannot land on an object continuously moving in perfectly timed circles. Once such a level of mastery is achieved – the defender can decide the level damage perpetuated upon the attacker depending upon circumstance. Should the body of the attacker be temporarily or permanently disabled? Should the body of an attacker be only (gently) nullified as if in play? Someone who has mastered Tai Sabaki (体捌き) possesses all these choices. This is why the Wado Ryu Style of Karate-Do posits the highest ideal of a defender possessing the ability to prevent damage to both their own body AND the body of the opponent! An ideal of the highest nobility!

0 Comments

At the end of the day, in a threatening position, an individual purporting to practice a traditional (Chinese) martial arts - must be able not to win trophies or gain coloured belts or sashes - but rather REMOVE the systemic threat existing in the immediate environment through the use of a 'decisive' act of disciplined violence. Unlike the modified martial arts used within modern sports, an 'effective' technique being deployed in a 'live' situation does NOT need to look good or conform to an unreasonable 'aesthetic'. The person being threatened, at the moment the decisive action is being deployed, is entirely on their own for the duration of the conflict. Whatever happens next becomes a matter entirely of their own affair - as other people (logically) tend to 'distance' themselves from the conflict as a matter of life-preservation and self-defence by association. Of course, the action might go wrong and the chosen technique fail to work. Above, a conflict begins between two young men (speaking Putonghua) arguing over who has the right to 'sell' in a certain area - with an Old Man attempting to de-escalate the situation. The young man launches a 'punching' attack which works precisely as intended. The armed young man is knocked down and is unconscious for a short time. He is kept in place by a foot on the chest - as NO further action is used against him once the knife is taken away from him. As you can see - violence is a horrible answer to any question - and a well disciplined and peaceful society is preferred over that of a violent situation. In this circumstance, the young man with the knife may well be suffering from mental health issues that now need to be treated. Although violence is NOT the answer - even though it may be required at certain times - when violence is needed it must be decisive enough to END the over-all level of existential violence and prevent any further damage to society and the people living in it!

Translator’s Note: I encounter this (historical) Goju Ryu article on the Chinese language internet (Baidu). It appears to be a Chinese translation of the biography of Higaonna Kanryo (1853-1915) as preserved by Higaonna Morio (b. 1938) in his book entitled ‘The History of Goju Ryu Karate-Do' - which I believe has been published in English – but is difficult to find nowadays. I have carefully worked my way through this Chinese language text and generated a reliable English language translation. Sometimes, when articles of this nature appear in different languages (and are intended for different cultural milieus), the way the information is presented can sometimes be moulded and shaped to match the very different reading communities the data is intended to penetrate, etc. Originally, Miyagi Anichi (宫城安一) transmitted this information to one ‘Lin Shifan’ (林师范). Although I have no way of knowing who this is, from the other translation work I have completed on this subject, I know that the real name of Pan Yu Ba (潘嶼八) was ‘Lin Dachong’ (林达崇) and that the ‘Lin’ (林) family of the Fuzhou area of Fujian province are very interested in this matter. A number of this ‘Lin’ (林) family-clan are practitioners of various types of ‘White Crane Fist’ (白鶴拳 - Bai He Quan) with many assuming a historical ‘link’ with Higaonna Kanryo – either directly or indirectly! One point that needs clarification is the following. I appreciate that the island of Okinawa was devastated during the Battle of Okinawa during the Pacific War (1941-1945) and that a great deal of irreplaceable history and culture was destroyed. This means that the historical evidence gathered from Fuzhou by Higaonna Kanryo, Miyagi Chojun (and others) and brought back to Okinawa was lost. However, the Battle of Okinawa did not happen in Fuzhou – although South China did experience the equally devastating Taiping Uprising and the Hakka Punti Clan Wars both in the mid-19th century with millions being killed. However, despite this violence and upheaval Miyagai Chojun found evidence of the existence ‘Liu Long (Gong)’ in 1915 when he visited Fuzhou (in the form of an engraved tombstone) - despite the cultural shock of the 1911 ‘Nationalist’ Revolution! The Anti-Japanese War of Resistance was also equally disastrous (1931-1945) as was elements of the Chinese Civil War (which ended in ‘Liberation’ in 1949). Although some elements of the ‘Cultural Revolution’ (1966-1976) targeted well-known structures and historical buildings, etc, it is doubtful that the tombstone of a relatively obscure martial arts Master would be touched – as China is full of such people who routinely attain extraordinary levels of inner and outer martial skill (even where destructive acts were caried out – it is generally the case that every object or structure targeted was ‘recorded’ and in later times repaired or replaced)! As this is the case, and given that the physical evidence has been lost in Okinawa – why is there no obvious physical evidence in Fuzhou itself? This is quandary all of its own - which is part of a much bigger picture - involving many hundreds if not many thousands of people in China, Okinawa and around the world all of whom possess a genuine respect and admiration for the style of Goju Ryu. These people are seeking to uncover its historical roots for all to see! No stone should be left unturned regardless of its weight or shape! There should be no areas of taboo when researching this matter. ACW (4.8.2022) In fact, there are not many records about the deeds of Higaonna Kanryo (东恩纳宽量 Dong En Na Kuan Liang) – a situation compounded by the fact that Mr Miyagi Anichi (宫城安一 - Gong Cheng An Chi) asked for confidentiality. Therefore, people outside know very little, but this is a situation we intend to change when the ‘Higaonna Kanryo Memorial Hall’ (纪念馆 - Ji Nian Guan) is finally completed and opened, by making available further biographical details that were previously ‘secret’. Part of this historical project is to highlight and confirm China’s vital (cultural) contribution to the origination of the ‘Goju Ryu Karate-Do' (刚柔流空手道 - Gang Rou Liu Kong Shou Dao) style of Okinawan martial arts - or the ‘Hard-Soft School Empty Open-Hand Way’. Indeed, we should be proud about this association between Okinawa and China and make this fact better known amongst the people. Furthermore, many of us in Okinawa are of ethnic Chinese descent and we should be proud of this fact. Needless to say, without the effort and sacrifice carried-out and experienced by Higaonna Kanryo – there would be no Goju Ryu Karate-Do in this world! The ethnically Chinese ‘Shen’ (慎) family of Okinawa changed their family to ‘Higaonna’ (东恩纳 - Dong En Na). This is correct as the family of Higaonna Kanryo were of ethnic Chinese descent and were one of the many Chinese families that migrated from China to settle in Okinawa (Ryukyu). Higaonna Kanryo was the 10th generation descendent of the Chinese people who originally migrated to Okinawa (Ryukyu) from China – and the name of his father was ‘Higaonna Onna’ (东恩纳宽用 - Dong En Na Kuan Yong). Why Did the Higaonna Family Change Their Family (Surname)? Why did they change their family (surname) from the Chinese-sounding ‘Shen’ (慎) to the Japanese-sounding ‘Higaonna’ (东恩纳 - Dong En Na)? Legend states that after Japan annexed and occupied the Ryukyu Islands – all the ethnically Chinese people were forced to change their family (surnames) to Japanese-sounding equivalents. The new Japanese government control made it illegal for ethnic Chinese families to continue to use their ancestral names. This is when the Chinese ‘Shen’ (慎) family changed their name to the Japanese-sounding ‘Higaonna’ (东恩纳 - Dong En Na) surname. However, despite this new Japanese policy – many ethnically Chinese families living in Okinawa (Ryukyu) publically presented their family (and ‘first’) names in the Japanese language (for official, commercial and legal reasons) - but carried on in secret giving their children ethnically Chinese family (and ‘first’) names so that they would not forget that they were of ‘Chinese’ ethnic and cultural origin! Therefore, the ‘Chinese’ name given to ‘Higaonna Kanryo’ was ‘慎善熙’ or ‘Shen Shanxi’! What Was the Real Reason Higaonna Kanryo Travelled to China to Learn Martial Arts? The Shen family was engaged in the maritime business and possessed a fleet of ships that collected, transported and delivered trading goods between the many Ryukyu Islands. When Higaonna Kanryo was aged around 13 years (and four months) old, his father – Higaonna Onna – was killed by a knife-blow whilst engaged in a dispute with an individual in a tavern. After this, the family business was taken over by relatives. Although still young, even at 13 years of age, Higaonna Kanryo was already a well-built youth! He had heard that Chinese martial arts possessed the ability to kill enemies with a single blow and so he naively thought that if he could travel to China – learn these deadly arts – and then return to Okinawa to take revenge on his father’s killer! Travelling to China in those days invariably meant travelling to ‘Fuzhou’ (the capital city of Fujian province), a process which was legally difficult and depended primarily upon the weather! As the boats depended upon sails – and given that there were no motorboats in those days – the weather had to be just right before any journey could begin. The wooden boats of those days were very ‘light’ and built for in-coast travelling at speed. There were not very robust and not suited for the wide-open seas. If a storm was encountered at any point on the journey – certain death was almost ensured! All these difficulties existed even if the legal documents to travel to China could be cleared by the Japanese and Chinese Authorities! All these difficulties formed barriers between Higaonna Kanryo and his wish to travel to (Fuzhou) in China! Higaonna Kanryo, however, did eventually manage to achieve all these objectives using determination and a logical approach to planning. He took-on one task at a time and achieved everything in the correct order. This is how he eventually achieved his objective of successfully sailing from Okinawa to Fuzhou! Upon arrival, Higaonna Kanryo secured a place of residence in the ‘Ryukyu Pavilion’ (琉球馆 - Liu Qui Guan) - a ‘Hotel’ and ‘Hostel’ situated in Fuzhou but paid for and administered by the Ryukyu government. This establishment catered for the everyday living requirements of visiting Okinawan travellers. After he settled down and became familiar with the local culture, Higaonna Kanryo started to enquire if anyone knew of a martial arts teacher who would be willing to take-on a new apprentice? Of course, this was not an easy task as most Chinese martial arts lineages were ‘closed’ at that time and highly ‘secretive’. Fathers usually taught sons and outsiders were not permitted to learn family martial arts! An ‘outsider’ was not only a foreigner from another country – but any Chinese person originating from a different name-clan! Higaonna Kanryo was 15 years (six months) old and an ‘out-of-towner'! As a result, he searched for nearly a year but could not find a teacher. The person in charge of the Ryukyu Pavilion knew of his painstaking efforts and eventually decided to introduce him to a local 40-year-old person known publically as ‘Liu Long’ (刘龙) - (also referred to as ‘Gong’ [公 ]) a well-known and well-respected martial arts teacher! (This is a ‘transliteration’ - see Note 1). This Liu Long (Gong) was very famous in the marketplace. Although he was highly skilled in self-defence, he did not make a living by teaching martial arts. It seems that teaching martial arts was a matter of honour (not profit) for this Master, and this made his teaching method rather strict. He earned his living through the business of transporting building materials. After Higaonna Kanryo was introduced, he was given the task of carrying bricks and tiles during the day to make a living, and only practiced martial arts at night. The tiles and bricks were heavy and had to be moved by hand from the storage area to the dock, and from the dock onto waiting barges (large, wooden boats). A working day lasted between 8-10 hours of continuous muscular effort! Higaonna Kanryo could lift one or two hundred kilograms of bricks and tiles each time and walk with this load up and down steps and across narrow planks of wood without dropping the load or losing his footing! A strong adult male would find this type of work difficult – how much more so would a youth of 15 or 16 years old! This was tremendously hard work – as can be imagined - but this kind of physical training laid a sound foundation for a wide range of martial arts techniques! As the working environment was next to the river, Liu Long (Gong) possessed a house (and workshop) which were built by the river. This comprised of a two-storey construction made of bamboo with Liu Long (Gong) living on the upper floor with his family and Higaonna Kanryo living on the next level down. This lower level was about 2-3 meters up from the water surface, and possessed a floor made of bamboo branches which left many gaps! This meant that every night a cold wind blew through the structure arising from the water-surface just beneath the bamboo floor! This created a very cold floor that was often near to freezing – a situation which made lying down and properly sleeping a very difficult task! To survive the cold, Higaonna Kanryo would get up and practice the ‘Sanchin’ (三战 - San Zhan) or ‘Three Battles’ dynamic tension exercise until dawn – when the coldness would begin to pass! This may well explain why Higaonna Kanryo’s ‘Sanchin’ Kata was considered so good! (See Note 2). Note 1: It is believed that ‘Liu Long’ (刘龙) is his real name, with the designation ‘Gong’ (公) being honorific. From the Fuzhou language that spread to Okinawa – his name is used whilst describing his fast feet – which phonetically transliterates as ‘ka gin ka ryu ryu’ (‘Really fast feet of Liu Long’). This suggests that ‘Liu Long’ (Ryu Ryu) is his real name – and not ‘Liu Longgong’. However, this does not exactly corelate to ‘Ryu Ryu KO’ (如如哥 - Ru Ru Ge). Note 2: Higaonna Kanryo’s ‘Sanchin’ Kata was declared to be ‘excellent’ after he returned to Okinawa! This came about after a local martial artist named ‘Hucheng’ (湖城) challenged Higaonna Kanryo – stating that his ‘Sanchin’ Kata was superior! The allegation was that Higaonna Kanryo’s ‘Sanchin’ Kata was inferior is some way and this created a great controversy throughout Okinawa! Many local martial artists were eager to see this matter settled once and for all. Therefore, a doctor (and his medical assistants) from the Okinawa Prefectural Hospital was invited to help with the investigation. He was given the task of deciding from a medical point of view, which version of the ‘Sanchin’ Kata generated the greater strength! This led to Higaonna Kanryo and Hucheng demonstrating their respective versions of the ‘Sanchin’ Kata in-front of a panel of medical experts! The performances were examined by the medical doctor who paid close attention to the length of time each inward, outward and transitional breath took, the capacity to take-in and expel ‘air’ (气 - Qi), and the consistency and firmness of muscular ‘tension’ (力 - Li) achieved. The full breathing and muscular tension had to be maintained whist stepping forward and back, and whilst changing the positions of the arms and hands, etc. The medical results proved that the ‘Sanchin’ Kata as performed by Higaonna Kanryo was several times more impressive (and effective) than the version exhibited by ‘Hucheng’. The doctors were surprised to witness the length and depth of each inward, outward and transitional breath made by Higaonna Kanryo as well as the extent of ‘qi’ energy he was able to accumulate and circulate! Furthermore, the doctors checked and confirmed that Higaonna Kanryo was able to ‘retract’ his testicles into the lower abdomen during his performance of the ‘Sanchin’ Kata – and retain this ‘retraction’ with no difficulty whilst stepping in different directions! This is an ancient martial arts ability that is rare in the modern age and is termed ‘吊裆藏阳功夫’ (Diao Dang Cang Yang Gong Fu) or ‘Hanging Groin Concealment Positive Energy [Yang] Martial Self-Cultivation). This (internal) ancient martial arts method was developed to protect a male practitioner from being kicked (or otherwise ‘struck’) in the testicle area of the groin. When all these abilities were fully investigated and verified, the skill-level of Higaonna Kanryo was declared to be obviously of a far superior level! Indeed, the people of Okinawa were (and are) very proud of the ‘Naha Te’ (那霸手 - Na Ha Shou) style of martial arts Higaonna Kanryo practiced and taught. (‘Naha Te’ is considered the foundational forerunner to the ‘Goju Ryu’ [刚柔 - Hard-Soft] style of martial arts that was later developed by his disciples – specifically ‘Miyagi Chojun’ [宮城 長順]). Of course, ‘Naha’ is a famous city situated to the South of Okinawa. Fifteen years later, Higaonna Kanryo had developed from a robust boy to a very strong and mature male martial artist! Due to the increasing international tension of the time, foreign powers began to invade and occupy China, and Liu Long feared that there would be wars. He advised his disciple – Higaonna Kanryo – to return to the relative safety of his home in Okinawa to avoid the danger. Before he left, however, Liu Long transmitted the essence of the martial arts style to him and gave him full permission to transmit this style to others! As Higaonna Kanryo was very loyal to his teacher – Liu Long – he was very reluctant to leave his side and return to Okinawa! Higaonna Kanryo only obeyed Liu Long’s instruction with a sincere regret! When he returned to Okinawa, Higaonna Kanryo had to take-over his father’s business of operating water freight and could not yet teach the martial arts to others that he had learned in Fuzhou (China) - although he continued to practice in private. Eventually, however, his ship sank in a typhoon and this business came to an end. Although it was common knowledge that Higaonna Kanryo had travelled to Fuzhou to train in Chinese martial arts as a means to enact revenge upon his father’s murderer – time passed, and he took no action against the killer! Instead, the now older and more mature Higaonna Kanryo was a strong role model who upheld the law and was respected by the entire community! He seemed to show no interest in his father’s murderer and simply went about his day! Months went by and nothing happened. Meanwhile, the murderer of his father was aware of this situation and as time went by his mental state became ever more restless and apprehensive. He had no idea when Higaonna Kanryo would take action or make his move. From his perspective – the psychological and physical pressure became almost unbearable! This prompted the killer to visit the home of Higaonna Kanryo and knelt down outside his front door and bowed his head to the ground! He begged for forgiveness and explained that both he and his father were drunk, and both had got into an alcohol-fuelled brawl which ended in the latter's death. He further explained that it was his father who drew his own knife and attacked him - and that he was forced to defend himself! He took the knife off his father and accidently stabbed his father with it – who died from the wound! He was arrested tried by the Okinawan Authorities – who agreed upon the details of the case (confirming that it was an act of ‘murder’ carried-out in ‘self-defence’) and returned the knife to the Higaonna family (as it was their property)! The individual concerned was sent to prison and had served his time. After listening to this story, Higaonna Kanryo agreed with this explanation and stated that this individual should no longer worry about the expected consequences of his actions! Higaonna Kanryo stated ‘Okay, I believe you. Forget about it!’ Many people had gathered to watch what they thought would be a good but one-sided fight – thought this was an anti-climax whilst others thought it was a good moral lesson concerned with proper virtuous action! Children in Okinawa were taught this lesson in their schools with this episode becoming widely known! The reaction and demeanour of Higaonna Kanryo was considered historically significant and a superb demonstration of ‘good’ behaviour versus ‘bad’ behaviour. There are many stories regarding Higaonna Kanryo but they differ in detail from those passed-on by Miyagi Chojun. There is a legend that Liu Long (Gong) made a living by weaving bamboo wares, but when Higaonna Kanyro was young, he did not understand this and only remembered the career that Liu Long (Gong) had taken-up later in his life. The ‘Yi Mou’ (一缪) biography suggests that the teacher of Higaonna Kanryo was the ‘Whooping Crane Fist’ (鸣鹤拳 - Ming He Quan) named ‘Xie Chongxiang’ (谢崇祥) who was also known as ‘Xie Ruru’ (谢如如). This is a story past down by the descendants of Master Xie Ruru – with some Goju Ryu practitioners believing this is the case. The problem is that according to a number of stories the age difference between Liu Long (Gong) and Higaonna Kanryo is at least 20 years. Whereas the difference between Xie Ruru and Higaonna Kanryo is only 1 year. Liu Long (Gong) died at least 15 years before Xie Chongxiang (who died in 1930). When Miyagi Chojun went to China to pay homage to Liu Long (Gong) in 1915 – Liu Long (Gong) was already dead (the exact date is unknown) – whereas Xie Chongxiang was still alive at this point. This has led to a number of disrespectful stories developing regarding Goju Ryu practitioners not knowing who their Chinese ancestral Master was and where the respect should be directed, etc! As there is a doubt about which name should be engraved upon the ancestral gravestone – there is a joke about Goju Ryu practitioners ‘waiting’ for a tomb stone to appear! These disrespectful attitudes often emerge from people who are jealous of the excellent standard of martial art technique found within the Katas of the Goju Ryu system! Having said all this, it is also important to state that Higaonna Kanryo was born and brought up on a boat and did not receive any formal education. In addition, he went to Fuzhou, China to learn martial arts for 14 years (and 5 months) - and worked and practiced every day. As this was the case, it was impossible for him to receive any formal cultural education. As a consequence, Higaonna Kanryo had a very limited ability to read and write. This meant that he could not record his experience in writing whilst living and training in China! Miyagi Chojun was Higaonna Kanryo’s only ‘inner disciple’ (内弟子- Nei Di Zi) and when his name was transmitted to Miyagi Chojun – it was only in the local colloquial dialect – and even then, only phonetical! All the other ordinary students training under Higaonna Kanryo did not even receive that information! Originally, when Miyagi Changshun went to Fuzhou to pay homage to Liu Long (Gong), he had Liu's name. He discovered his date of birth - and the date of his death - which were all recorded on his tombstone. It is a pity that all the information was destroyed in the Battle of Okinawa. Mr Shang Anyi (上安一) states that if a lineage is not clear – then it should not be taught as fact. (This is a common attitude found within tradition Chinese martial arts). A problem has been caused by the very success of Higaonna Kanryo’s travelling to China and learning a system of traditional Chinese martial arts! Not only did he transmit this to Okinawa in a clear and concise manner, it has been successfully passed on in a technically pristine state! Goju Ryu has blind spots and vague details in its history - yes – but it has spread far and wide and has influenced the development of many other martial arts styles, schools and systems! There is a central truth to its transmission – just as there is a body of accrued material that is difficult to prove or disprove! It is an ongoing project as many people in China and Okinawa strive to clarify this matter! It is beyond question that through Higaonna Kanryo’s efforts – a hundred flowers of cultural influence have blossomed! Surely, Higaonna Kanryo would have found this truly unexpected! Source: Miyagi Chojun (宫城长顺 - Gong Cheng Zhang Shun) Transmitted to Miyagi Anichi (宫城安一 - Gong Cheng An Yi) Miyagi Anichi (宫城安一 - Gong Cheng An Yi) Related to Lin Shifan (林师范) The History of Goru Ryu Karate-Do - By Higaonna Morio (东恩纳 盛男 - Dong En Na Sheng Nan) Original Chinese Language Article:

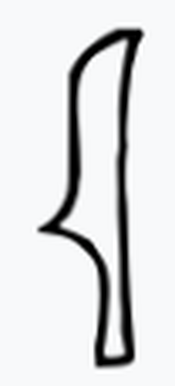

https://tieba.baidu.com/p/1307549295 东恩纳宽量的简史 2011-12-03 12:10 有关东恩纳宽量的事迹其实记载的不多,加上宫城安一先生要求保密,所以外面的人们所知甚少,我们希望在东恩纳宽量纪念馆落成之际把部分资料解密,让大家了解多些这位对刚柔流空手道的成立起了重大作用的中国华侨,作为中国人我们亦应感到自豪。没有他,这世上可能没有刚柔流空手道。 慎氏家族改姓为东恩纳的原因 东恩纳宽量是移居琉球的中国人慎氏家族的后裔,传到他已经是第 10 代了,其父名东恩纳宽用。 为什么他们会由姓慎改为姓东恩纳呢?传说当年日本占领琉球后,迫使所有定居在冲绳的中国人归化琉球及不准使用中国姓氏,于是慎氏家族改姓为东恩纳,但其每一个后代子孙都必拥有中国名字,以示不忘中国之本。故此东恩纳宽量亦不例外,他的唐名(中国名)叫慎善熙。 东恩纳宽量到中国学武的真正原因 慎氏家族是从事海运事业的,拥有船队运输各种物资往来冲绳岛各个岛屿。当宽量13/4 岁时,一天,他父亲宽用在酒馆内与人争执被人用刀杀死。宽用死后,家族生意被其他亲属接管了,当时宽量还是一个大孩子,整天在想着为父报仇,听说中国武术可以轻易的把敌人杀死,便天真地想到去中国学武,希望学成回来便可为父报仇 … 但当年要去中国(福州)并不容易也不简单,除了手续繁复外,还要看天气、风向等各种因素稳定后船只才可以开航的,原因当年并没有机动船,那些去中国福州的都是木制的帆船,如果遇到大风浪可以说是九死一生十分危险的,宽量搞了一年多才能以到中国求学为理由,拿到去中国的渡牒批文等有关的官方文件,达成去中国(福州)的梦想。 去到福州后,便在琉球馆(琉球政府办的旅馆)安顿下来然后便四处打听寻师学艺,然当时学武也有一点隐闭,对一个 15/6 岁的外地人来说实非易的,结果他找了近一年还找不到,琉球馆的负责人知道他的苦心,介绍他给当地一位 40 来岁,武功高强的老师刘龙(公)(译名)注 1。这位刘龙(公)在坊间是十分有名,虽然武艺高强,但并非以授武维生的,授武好像是他的业余爱好而且教学也相当严格。他是经营运输建筑材料生意的。宽量入门后,便安排他白天在做搬砖运瓦的工作以维持生计,晚上才练武。 当年运输砖瓦的工具是用一些较大的木船,搬砖运瓦上船可不是一件轻松的工作,每天 8-10 个小时,每次挑一两百斤的砖瓦,整天不停的在吊板上搬上搬下就算成年人也会感到吃力,何况一个仅十五六岁的大孩子?其辛苦之处可想而知。但这样的肉体磨练却为宽量的练武奠下良好的基础。 因为作业环境在河边,刘龙(公)的住家和工场都建在河边上,一栋两层高,用竹建成的房子,刘龙(公)跟家人住在上层,宽量就住在下一层;下层离开水面约 2-3 米高,用竹枝拼成的地板是会有很多缝隙的,每到深夜,冷风由竹地板下吹上来,宽量被冻到不能安睡,终于他找到一个驭寒的方法,便是起来练‘三战',一直练到天亮。 这可能是他的‘三战'注 2 那么出众的背后原因? 注 1 推测 刘龙 是他的正名,‘公'则可能是一个尊敬语。由一句流传到冲绳描述他的脚法快的福州语:“ka gin ka ryu ryu”(脚真快刘龙)中可以推测到他的名字是刘龙。并不是刘龙公,更不是什么‘如如哥'。 注 2 这事发生在宽量回去冲绳后的--- 一位姓湖城的武术家向人扬言自己的‘三战'比宽量的高明,结果引来争论,其他练武的人们亦感兴趣,故找来冲绳县立病院的医生来帮助考察,希望从医科学角度判断那一位的‘三战'比较强。 于是湖城及宽量一齐在医生们面前演示他们的‘三战',在众医生的检验下,发觉宽量除了在运气时的肌力,技术及呼吸法都胜湖城几倍外,更令医生们吃惊的,宽量每在运气时,竟可把睾丸同步吸入小腹内(古代武术家因怕跟人交手时被踢中裆部,故会去练这种吊裆藏阳功夫),结果当然是判宽量的‘三战'技高一筹。见宽量的武功如此高深,冲绳人都引以为荣,把他所教的武功尊称为那霸手(= 现代的刚柔流),视之为代表那霸(城市名字)的武术。 15 年后,宽量已由一个大孩子变成一个武功高强的成年人,因时局日催紧张,列强开始入侵中国,刘龙恐会有战乱,着宽量离开福州返去冲绳,并谓自己毕生所学的全部已授予宽量,亦希望宽量把他所教与的武功流传下去,宽量本不愿离开福州,但因为刘龙的坚持,唯有告别恩师返回冲绳。 返回冲绳后宽量并不是第一时间去授武,而是做回父亲的老本行经营水上货运(后因船只遇到台风沉没,生意亦告结束)。 知情人都知道宽量到中国学武是为了报杀父之仇,当他回冲绳后,大家都抱着将有好戏看的心态来看待,但一直等了多个月,还未见宽量有任何行动,当年杀死他父亲的人更寝食不安,不知何日宽量会找上门来,终于,他受不住这种压力,自动登门去到宽量家里,在门外跪下向宽量解释当年因大家喝了酒而争吵,是你父亲拔刀刺我,混乱中反被我刺死的,官府亦判我为自卫杀人,而且刀是你父亲带来的··,宽量很平静的看住此人并说:“好,我相信你,此事算了罢!”,在旁边堆满了准备看好戏的人群一方面觉得没趣,另一方面都赞赏宽量的明白事理,后来还把今次的事件用来教育子女,要学宽量般明事理,懂分黑白. 坊间对宽量的事迹有多种传说,但与宫城长顺传下的有分别,举一个例,有传说刘龙(公)是从事编织竹器为生的,而不知道那是他因年纪已老才改行的后期事业。 另一缪传是说宽量的师父就是鸣鹤拳的谢如如 谢崇祥)相信是他的后人自编自说的故事,有关的传说资料都显示出刘龙跟宽量的年龄相差最少有二十多年,而不是他们传说的宽量的师父就是谢崇祥,因两人的年岁只相差 1 岁,而且刘龙去世的年期比谢崇祥最少早 15 年,因宫城长顺去拜祭刘龙(公)时是 1915 年(刘是 1915 年之前已去世的,正确日子不详),而谢崇祥还未死,他是 1930 年才去世的。 这个资料不但给那些想利用宽量事迹的灰色地带来吹捧自家武术的打了一记闷棍,还大大的讽刺了那急不及待的“立碑”笑话。真的是一起‘伪造师承,强迫入门兼立错碑'的武林大笑话。 话说回头,宽量因自小在船上生话,并没有受过什么文化教育,加上后来去了中国福州学武整整 14/5 年,每天干活练武,更没可能去接受文化教育,所以他的文化水平很低,正因如此,他无法把在福州的经历用笔写下, 以至后来连师父的名字都是用口语(拼音)来传述给宫城长顺(他唯一的内弟子),其它普通的弟子根本无从知悉。 本来宫城长顺去福州拜祭刘龙(公)时是有把刘的姓名,出生日期及忌辰等从墓碑上记录下来的,可惜所有的资料都在冲绳战役中被毁灭了,加上安一先生说如非认可传人是不应把流派的历史传授(这是传统武术的一惯做法),但却做成今天刚柔流空手道的历史存有灰色地带及很多由其他人创作的穿凿附会小道传说,刚柔流发展到今天,因盛名所致,做成百花齐放,真伪莫辨、版本众多,实始料不及。 资料来源: 宫城长顺传述给宫城安一,宫城安一师范再传述林师范 。 刚柔流空手道史 - 东恩纳 盛男著 Although the martial arts term ‘Ninja’ is a distinctly ‘Japanese pronunciation – the two ideograms used to express this concept are of Chinese origin – namely ‘忍者’ (Ren Zhe). Whether this concept originally spread from China as a martial arts principle – or was distinctly developed in Japan - is open to debate. Certainly, the ‘Ninja’ of medieval Japan occupied entire clan-systems which ‘mirrored’ perfectly their Samurai equivalents with the only difference being that the Samurai clans were socially accepted and the ‘Ninja’ clans were clandestine and considered ‘illegal’. The ‘Ninja’ communities were made-up of the peasantry and any outcast members of the nobility and criminal fraternity, etc. Although the ‘Ninja’ communities were hidden from open view, they were disciplined, followed strict codes of conduct and were dedicated to perfecting many different martial skills designed to ‘counter’ or ‘negate’ every martial advantage the Samurai believed they possessed. In-short, the ‘Ninja’ communities represented a ‘different’ but related blue-print for Japanese feudal society – perhaps one that was internally democratic and fairer than its Samurai alternative, as women were considered ‘equal to men – and practiced martial techniques designed by women for women to use on the battlefield or during ‘assassinations’ - a key skill of the ‘Ninja’ warrior. The character ‘忍’ (ren3) is comprised of a contracted version of the lower particle ‘心’ (xin1) - which translates as ‘mind’ and ‘heart’ - and the upper particle ‘刃’ (ren4) - which represents a ‘bladed weapon’ such as a ‘knife’ or ‘broad-sword’, The Japanese version of this ideogram appears to have a handle affixed to a blade – a blade said to be covered in ‘blood’: When combined together, the ideogram ‘忍’ (ren3) suggests a situation where the human mind (and body) is said to be highly skilled swordsmanship – together with ‘tolerating’ the ‘lose’ of a certain amount of one’s own blood – as well as spilling that of the opponent. The training in this martial art is arduous and painful to experience – but this is the path that must be ‘endured’ if mastery is to be achieved. Whereas the ideogram ‘者’ (zhe3) is comprised of the lower particle ‘白’ (bai2) which carries the meaning of the colour ‘White’, whilst the upper particle is ‘耂’ (lao3) and refers to a ‘an old man who is bent-over and has long hair’ - usually implying ‘acquired wisdom overtime’. Therefore, ‘者’ (zhe3) appears to mean a ‘body of expert knowledge acquired by an individual over a long period of study’. The combined term of ‘忍者’ (Ren Zhe) - or ‘Ninja’ - refers to the concept of an ‘accumulated body of knowledge and martial arts skill and acquired by an extraordinary person overtime’. Or, an ‘acquired body of knowledge and martial arts skill that transforms an ordinary person into an extraordinary person’. Related Terms:

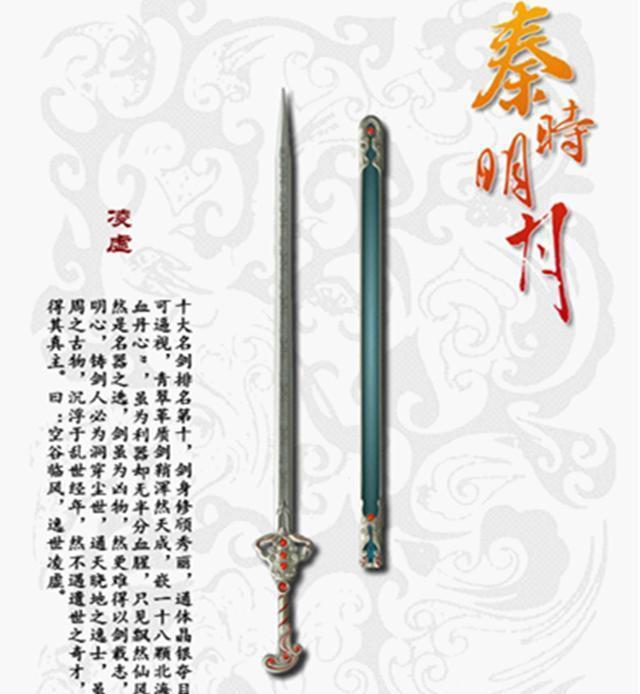

忍術 (Ninjutsu) - ‘Ren Shu’ = ‘Endurance Art’ 忍法 (Ninpo) - ‘Ren Fa’ = ‘Endurance Law’ Ninjutsu originally derived from an indigenous, traditional Japanese fighting technique known as the ‘Thorn Kill Art’ (刺杀术 - Ci Sha Shu) - perhaps implying the ability to ‘assassinate an opponent using a poisoned-dart'. Later, this art absorbed several Chinese cultural influences such as the ‘Art of War’ by Sunzi", and the martial principles contained within the ‘Six Secret Teachings’, etc. There is a legend that a Chinese Buddhist monk travelled to Japan early-on, and brought various Tantric Buddhist and Traditional Chinese Medicine techniques (perhaps around the 8th century CE) which were combined with Japanese Shintoism. This mixture of Chinese and Japanese martial elements was integrated to finally form ‘Ninjutsu’. The techniques of ‘evasion’ and ‘invisibility’ in were emphasised in the city – whilst ‘ambushes’ and the ability to suddenly ‘disappear’ was perfected in the mountainous areas. Chinese Language Reference: https://baike.baidu.com/item/忍术/381309 Translator’s Note: Although ‘劍‘ is pronounced ‘Jian’ within Putonghua (which is the dialect of the Chinese language spoken in Beijing) - also known in the West as ‘Mandarin’ (the language of the scholar-officials) - within the Hakka language ‘劍‘, is pronounced ‘Kiam’ (in the ‘Sixian’ variant) and ‘giam’ (in the ‘Meixian’ version). As the Hakka language is considered far older as the language of Northern China used by the ruling elites, It would seem that ‘kiam’ and ‘giam’ were the normal ways of pronouncing ‘劍‘ - and that the Cantonese people of the South (originally the ‘Tang’ people of the North before they migrated en masse) - logically adopted ‘gim’ as their rendition of ‘劍’. Of course, I am assuming that the Hakka pronunciation is ‘older’ and probably the ‘original’ rendition of ‘劍‘. The Hakka people, in full or in part, probably ruled China through the Qin and Han dynasties from the North of China (but not Beijing), before being forced into a number of historical migrations Southward over two-thousand years. Certainly, our ancestral ‘Hakka’ village in the Sai Kung area of the New Territories of Hong Kong not only upholds the Hakka martial traditions of North China – but when I was young, we were taught to refer to the ‘long sword’ as the ‘giam’ - a tradition we retain to this day. The ‘long sword’ is used within our practice of the single and double sword routines as is exclusively associated with advanced Taijiquan practice. ACW (21.2.2021) This ideogram dates back to the Bronze Inscription Characters of the Shang and Zhou Dynasties (c. 1600 BCE – 300 BCE) and was depicted in the following manner (amongst a number of similar of variants): This means that swords designed to be ‘long’ and ‘thin’ to varying degrees (made out of metal) probably developed during this era. Today, these ‘劍‘ (jian4) swords are around three-foot long and constructed from a sharp double-edged blade. Although designed for the expert (and ‘effortless’) ‘piercing’ of the opponent – such a weapon can be used to ‘hack’ and ‘slash’ if the situation demands (although this is considered very much a ‘secondary’ skill). The Confucian scholar carries this type of sword as a symbol of his ‘learning’ and his ‘academic’ authority – although like with the bow and arrow – such a scholar was expected to be a ‘Master’ of self-defence, particularly if he held Public Office. The opponent’s defence (and body) must be decisively penetrated without any undue effort due to a perfect timing, positioning and movement. Furthermore, as such a scholar possesses a ‘calm’ and ‘wise’ mind – at no point in the execution of his sword technique does his weapon become ‘entangled’ with the weapon of the opponent! All ‘movements’ pursued with the long-sword must be effortless and ‘touch’ nothing other than the surface of the body that is to be ‘pierced’. ‘劍‘ (jian4) is composed of the left-hand particle ‘僉’ (qian1) - the top part of which is ‘亼’ (ji2) - an ‘inverted mouth’ that is used here, to denote the meaning of ‘gathering in from three-sides'. The bottom part of which uses a double ‘兄’ (xiong1) which refers to ‘an elder brother’. The right-hand particle is ‘刂’ (dao1) which refers to a ‘knife’ or a ‘single-edged; blade. ‘刂’ (dao1) is a contraction of ‘刀’ which within the Bronze Inscription Characters is drawn in this way (despite the character dating further back to the Oracle Bone Inscriptions: When all this data is assembled into the ‘劍‘ (jian4) ideogram – it seems (to me) to read ‘community defence’. The elders of the community – symbolised by two mature but physically ‘fit’ older brothers used to bearing responsibility – unite to ‘protect’ a community (that is drawn together on three-sides) to form a more ‘solid’ centre that is easier to defend with ‘weaponry’. The ‘weapon’ in question has evolved from a simple (and shorter) single-edged blade – to that of a longer double-edged ‘sabre’ or ‘sword’ that requires an incredible amount of skill to use effectively in combat. As ‘劍‘ (jian4) is so complex when compared to the far simpler ‘‘刀’ ideogram depicting a short-knife – it would seem that an element of ‘elaborate’ ritual is implied in the formulation of a long-sword' that extends to its ‘ownership’ in peace-time, and its ‘usage’ in times of war! Certainly, Confucian scholars are considered academic ‘warriors’ who often carry the scabbarded long-sword in their right-hand which means they have no intention of ‘drawing’ and ‘using’ it. Order within society is maintained simply by the ‘presence’ (and the ‘use’) of the long-sword – although this level of harmony and tranquillity manifest in the outer world implies exactly same level of attainment within the mind and body of the scholar-warrior! Should a ‘divine’ violence be required on the physical plane, then the scholar-warrior carefully places the scabbarded long-sword carefully into his left-hand whilst he right-hand secures a firm grip upon the long-sword handle... Having to resort to ‘violence’, however, would be thought of as a ‘failure’ by the scholar-warrior – as ‘peace’ is always preferable to ‘violence’.

|

AuthorShifu Adrian Chan-Wyles (b. 1967) - Lineage (Generational) Inheritor of the Ch'an Dao Hakka Gongfu System. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed