1) A man named ‘Higaonna Kanryo’ existed.

2) He was born during the year 1853 CE.

3) He died during the year 1915 CE.

4) His primary disciple was Miyagi Chojun (1888-1953).

5) What we ‘know’ about Higaonna Kanryo derives from Miyagi Chojun.

6) The ‘nine’ martial ‘sets’ or ‘patterns’ attributed to Higaonna Kanryo possess a certain similarity to the various styles that comprise the ‘Southern Fist’ (南拳 - Nan Quan).

7) The name of his ethnic Chinese martial arts teacher in Fuzhou (Southern China) is said to be ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’.

8) Despite most of the martial ‘sets’ looking like various forms of ‘Southern Fist’ styles that nevertheless maintain ‘Northern’ looking ‘Horse Stances’ - the gongfu art that ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ specialised in is said to have been Fujian ‘White Crane Fist’ (白鶴拳 - Bai He Quan) - with the ‘Sanchin’ (三戦 - San Zhan) or ‘Three Battles’ Form – which Higaonna Kanryo altered by changing finger-strikes to closed-Fists, etc.

9) This ‘Southern Fist’ collection of Chinese martial arts was integrated with Ryukyu ‘Ti’, ‘Di’ or ‘Te’ (手) i.e., ‘Hand’ - and formed ‘Naha Te’ (那覇手). Higaonna Kanryo’s strand of ‘Naha Te’ formed the foundation of Miyagi Chojun’s ‘Goju Ryu Karate-Do' (or ‘Hard-Soft’ Empty-Hand Way) - registered as a ‘Japanese’ martial art during 1936.

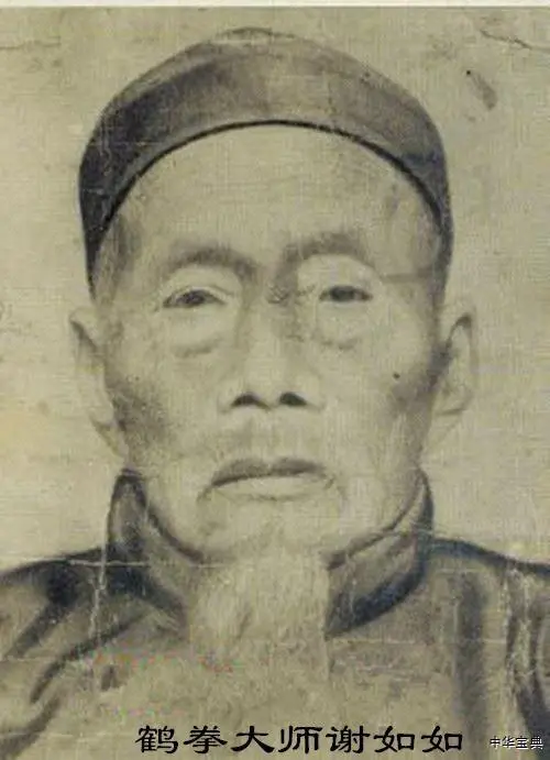

Although most of the above can be disputed, the reality of most of it lies in the existence of a) the graves of Higaonna Kanryo and Miyagi Chojun – and b) the techniques preserved within the movements of Goju Ryu Karate-Do. A central point of contention is ‘who’ was ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’? Although this issue has been solved within Mainland Chinese academia in 1989 (as Ryu Ryu Ko being the Chinese martial arts Master of ‘Xie Chongxiang’ [谢崇祥] 1852-1930) - this is not the case in the West or within a number of Japanese and Okinawan martial lineages (that refuse to accept the authority of ethnic Chinese historians). Why this is does not concern me here, but what I am concerned about is the lack of ‘logic’ (and ‘inverted’ thinking) surrounding the issue of ‘who’ Ryu Ryu Ko was.

a) Ryu Ryu Ko = the Okinawan ‘phonetical’ pronunciation of an ethnic Chinese martial arts teacher living in Fujian province.

b) As Higaonna Kanryo could not read, write or speak the Chinese language (despite being a descendent of ethnic Chinese migrants to Ryukyu in 1392 CE), he did not possess the ability to correctly hear, pronounce or write the ‘Chinese’ name of ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ - but could only ‘approximate’ its sound.

c) Higaonna Kanryo did NOT bring back any written evidence of the name of ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ using Chinese language ideograms. The fact that the Fujian dialect was used to pronounce this name is immaterial as ALL Chinese ethnic groups use exactly the same ideograms to record their names in written form.

d) Higaonna Kanryo’s ethnic Chinese surname is ‘Shen’ (慎) as pronounced in the Beijing dialect - but elsewhere exactly the same ideogram is pronounced (and ‘phonetically’ spelt in other languages) quite differently:

i) Guangdong (慎) = ‘San’

ii) Hakka Dialect (慎) = ‘Sum’ (Sixian) and ‘Sem’ (Meixian, Guangdong)

iii) Eastern Min – Fujian (慎) = ‘Seng’

iv) Southern Min – Fujian (慎) = ‘Sin’ or ‘Sim’ (Hokkien), ‘Sim’ (Teochew) and ‘Sim’ (Peng'im) ‘Sim’

e) The people in the Fuzhou area used to speak only the ‘Southern Min’ dialect. Given that Higaonna Kanryo’s Chinese name was ‘慎善熙’ (Shen Shanxi) - he may well have been known as ‘Sim Sianhi’ in the local dialect. The pronunciation shifts and the phonetic representation alters as the names traverse the hinterlands of China – but the foundational Chinese ideograms stay exactly the same. Higaonna Kanyro’s Chinese name means:

Surname: 慎 (shen4) = 340th Surname included in the book entitled ‘Hundreds of Chinese Clan Names’ (百家姓 - Bai Jia Xing) - and means ‘Those Who Become Prominent Through Being Cautious’. This surname may have originated with the ‘Mohist’ scholar known as ‘Qin Huaxi’ (禽滑釐) who lived during the latter part of the ‘State of Song’ (宋國 - Song Guo) [1046 – 286 BCE]. As the scholar – Mozi (墨子) lived between 468 - 376 BCE – Qin Huaxi must have existed at some point between 376 – 286 BCE. Later, the title of ‘慎子’ (Shen Zi) was conferred upon Qin Huaxi (or ‘Cautious Scholar’) and this is thought to be the origin of this surname.

First-Name = ‘善’ (shan4) - ‘Virtuous’

First-Name = ‘熙’ (xi1) - ‘Glorious’

What of ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’? There are no Chinese ideograms available from the time of Higaonna Kanryo’s visit to China. As ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ is a phonetic representation in Okinawa (now a Prefecture of Japan) - the Okinawans have used modified (or ‘distorted’) Chinese ideograms to represent these phonetic symbols. The three modified ‘Kanji’ Japanese ideograms used are ‘劉龍公’ or ‘Liu Longgong’. To an experienced reader of the Chinese written script, it is obvious that these three ideograms are not correct Chinese ideograms – and therefore cannot be representative of a genuine Chinese name. This situation has derived from the Japanese people ‘altering’ the structure and meaning of the Chinese ideograms that once formed the historical foundation of the Japanese system of reading and writing. In the West it is common for scholars and general readers alike to incorrectly assume that the above three Japanese ideograms represent the Chinese spelling of ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ - and that Higaonna Kanryo brought these ideograms back with him from China – when in fact none of this is true and is a product of a general ignorance in the West of the Chinese and Japanese languages. (Technically speaking, it is the altered structure of the second ideogram - ‘龍’ [long2] - which modifies the interpretation of the other two ideograms and confirms the ‘Japanese’ character of the entire expression). These three characters were ‘assigned’ by Japanese speakers to ‘represent’ the sound of the name of ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ to fellow Japanese speakers:

1) ‘劉’ (Liu3) = ‘Ryu’, ‘Riu’ or ‘Ru’ in Japanese phonetic representation. Although this ideogram is found in China, in Fuzhou (when used as a ‘surname’) it is more likely to be pronounced as ‘Lau’ and not ‘Liu’ as continuously asserted by various other non-Chinese sources.

Correct Historical Sequence: a) ‘Ryu’, ‘Riu’ or ‘Ru’ - b) ‘劉’ (Liu3)

Incorrect Historical Sequence: a) ‘劉’ (Liu3) - b) ‘Ryu’, ‘Riu’ or ‘Ru’

2) ‘龍’ (long2) = ‘Ryu’, ‘Ryo’ or ‘Ro’ in Japanese phonetic representation. Added to these definitions can also be the historical designations of ‘Ryou’ and ‘Rou’. When used as an ideogram in China, this structure refers to a ‘dragon’ or ‘serpent’, etc. In the Hokkien dialect of Fuzhou, this ideogram can be pronounced as ‘geng’, ‘liang’, ‘ngui’ and ‘liong’ depending upon context and exact location. The idea that this ideogram is pronounced ‘long’ in Fuzhou is incorrect.

Correct Historical Sequence: a) ‘Ryu’, ‘Ryo’, ‘Ro’, ‘Ryou’ and ‘Rou’ - b) ‘龍’ (long2)

Incorrect Historical Sequence: a) ‘龍’ (long2) - b) ‘Ryu’, ‘Ryo’, ‘Ro’, ‘Ryou’ and ‘Rou’

3) ‘公’ (gong3) = ‘Ku’, ‘Ko’ or ‘Kou’ in Japanese phonetic representation. When used as a Chinese ideogram refers to something being ‘public’, ‘equitable’ or ‘fair’. In the Hokkien dialect, this ideogram is likely to be pronounced ‘kang’ and ‘kong’ - and not ‘gong’ as usually asserted.

Correct Historical Sequence: a) ‘Ku’, ‘Ko’ or ‘Kou’ - b) ‘公’ (gong3)

Incorrect Historical Sequence: a) ‘公’ (gong3) - b) ‘Ku’, ‘Ko’ or ‘Kou’

It is impossible for Higaonna Kanryo to have brought back the name of his ethnic Chinese martial arts teacher expressed in a ‘Kanji’ (Japanese) modified script! To assume that he did this is illogical and counter intuitive and yet such an assumption underlies many Western, Okinawan and Japanese attempts at constructing historical narratives that diverge from those advocated by the Mainland Chinese scholars. Interestingly, only in ‘Putonghua’ are the Chinese ideograms ‘劉龍公’ pronounced as ‘Liu Longgong’! In the Hokkien dialect it is more likely that ‘劉龍公’ would be pronounced as ‘Lau Gengkang’ or perhaps ‘Lau Nguihong’, etc, nothing like the ‘Liu Longgong’ contrivance found throughout non-Chinese literature! Therefore, through this application of basic logic it can be proven that ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ historically preceded ‘劉龍公’ - whilst many (if not all) extant Western narratives continuously assert that ‘劉龍公’ historically precedes ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’! Finally, having discussed this matter with a number of ethnic Chinese speakers, it is generally believed that it is unlikely that a person would be named ‘Dragon Public’ (龍公 - Long Gong) as ‘Ryu Ryu Ko’ would have been if his Chinese name was written as ‘劉龍公’ or ‘Liu Longgong’. The word order is transposed and the concept highly unlikely as dragons in China are ‘elusive’ i

RSS Feed

RSS Feed