|

When running with the weighted rucksack – I use the two broad aspects of Daoist breathing usually termed ‘natural’ and ‘correct’. Bear in mind that this ‘moving’ activity is not the complex seated ‘neidan’ practice and is not subject to that type of control. Instead, as the bodily frame is placed under intense pressure, what is required is deep and full breaths, usually in and out of the mouth. This is because unlike the state of perfect balance that is constructed during the practice of Taijiquan (where the breath is taken in through the nose and expelled through the mouth) - running with a weighted rucksack overloads the biological processes to such a high degree that the maximum amount of oxygen is required to maintain its function. This is achieved by breathing in and out through the mouth. Once the parameters are set, what then is ‘Daoist’ about this practice? Natural breathing requires breathing deeply into the lower abdomen – this emphasises the use of the middle and lower-lung capacity – with the minimum of upper-lung capacity. Correct breathing requires the pushing-up of the diaphragm so that the inward breath is compressed from the expanded lower-lung and into the middle and upper-lung. Correct breathing inflates the usually neglected upper-lung capacity which is full of highly dense oxygen-absorbing body-cells. Generally speaking, the upper-lung is often used by the body in ‘emergency’ breathing if the body has become injured, ill, or is inhabiting an oxygen-deficient environment. The ancient Daoists seem to have understood that there is something special about the little used upper-lung within everyday life – and with this understanding they formulated a physical method of breathing that allows a voluntary access of this area. I tend to use ‘natural’ breathing when running with the weighted rucksack – but I switch to the ‘correct’ method when I need to stop to cross the road and/or significantly change direction. I usually take three full ‘correct’ breaths (which oxygenates the body to a greater degree) and then switch back to ‘natural’ breathing which is what I refer to as ‘maintenance’ breathing. Correct breathing in this context is not ‘maintenance’ breathing and should not be confused with the purpose of ‘natural’ breathing. Furthermore, the perspective I am giving here only makes sense when discussing weighted rucksack running. As weighted rucksack running using ‘natural’ breathing dramatically diminishes the oxygen levels in the body (stabilised through fitness levels) – ‘correct’ breathing represents a rapid intake of new oxygen by switching the emphasis of how the breath is managed.

0 Comments

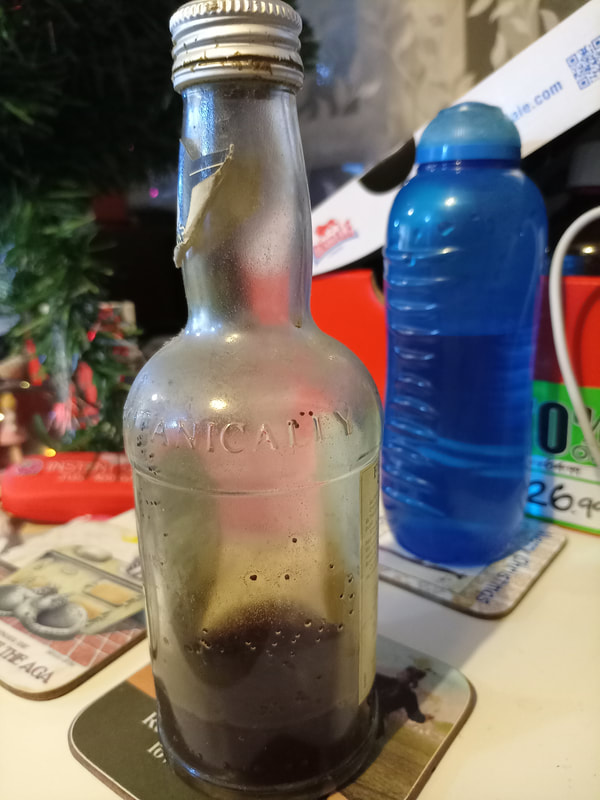

Our family style of Hakka Gongfu involves "Rucksack" running as both an "External" and an "Internal" practice method which builds muscle and joint power, bone strength, and psychological determination and indomitable spirt! As the pack weighs 56 lbs at its maximum weight (it can sometimes be raised to 76 lbs - but this is rare) - it is also a good indicator of developing and maintaining (skeletal) body-alignment - important for dropped body-weight and rebounding power found in the Internal method found in Taijiquan. When young, rucksack running is "External" - whilst for the older practitioner rucksack running becomes "Internal" - and has to be modified as a practice. Long distance running can be interspersed (or changed with) the shorter distances involved in circuits-training. Either way, the positive effects on the mind and body are absolutely the same: I have been pursuing a three-month circuit-training of five-days a week running three-time around the block (Monday-Friday) - carrying the 56 lbs pack. Running in urban environments is easier in one way as the surfaces tend to "flatter" than their "cross-country" (off-road) equivalents. However, running with a weighted rucksack is dangerous as when falling down the impact with the ground is magnified by the extra weight being carried. Falling upon grass, in mud or through water, for instance, is preferrable to falling upon concrete, as such a tumble "cushions" the fall. Yesterday (Monday), at around 830 am, I was slightly distracted whilst running over a broken piece of tarmacked pavement. This happened during the 66th run of my intended 70 - a training stint which will conclude this Friday (December 22nd, 2023). My legs were cut-out from beneath me and I fell onto my hands and knees - with the rucksack propelled upwards and over my right-shoulder. My palms soundly struck the pavement - saving me from a face injury - with my well-conditioned hands suffering no damage. Most the weight, however, entered the ground through my left-knee. My right-knee took about half as much impact. the friction (heat) between the surface-skin of my knees and the fabric of my running-trousers caused the surface-skin to "rub-off" - as can still be seen above. This is why I now have substantial knee-abrasions. A passing neighbour - who was astonished to see me tumble past him - stopped to help me up. This was not as easy as it might have looked - as I had to readjust the heavy pack, and rearrange my legs and knees to attempt an upward thrust from the ground in good order (from a kneeling on one-knee position). This I successfully achieved - thanking my Muslim neighbour for his truly caring attitude. This is why I replied "Peace to you - my friend"! I then reassumed my training - showing a "straight" and "committed" mind-set in the face of adversity - finishing that day's training. When I got home, my partner - Gee - carried-out her usual "nursing" function of repairing the war-wounds of her Hakka Warrior husband using the family Dit Da Jow to clean and dress the wounds. Today, I was up early to continue my training in the rain!

Wikipedia is a wealth of sagely advice – much of it misleading, incomplete and out of context. For instance, the author dealing with the ‘Tai Sabaki’ page - states that the usual interpretation of Tai Sabali in the West which involving ‘evasion’ is ‘wrong’. However, if an individual can ‘read’ Chinese and/or Japanese ideograms – it is obvious that whatever this concept is - ‘evasion’ forms a central aspect of it. The author in question does not fully comprehend the entire concept of Tai Sabaki and is attempting to join the two ends of an idea together whilst omitting a (vast) theoretical centre-ground! 1) 体 (Tai) - Japanese Equivalent of Chinese ideogram ‘體’ (ti3) = ‘body’ This is related to a body (comprised of - and structured by - its internal bone structure) which is augmented in the physical world through musical rituals (involving drumming) and the adornment of jade of jewellery. The body is enhanced by the placement and alignment of its inner structure and the means (rituals) through which this body traverses the outer world. That which is ‘detrimental’ is avoided and that which is ‘nourishing’ is embraced. There is an implication in the Japanese language that ‘体’ (Tai) refers primarily to the trunk and the abdomen – and only secondarily to the limbs. It is the ‘centre’ of the body which has priority over the ‘periphery’ of the body. 2) 捌 (Saba) - Japanese Equivalent of Chinese ideogram ‘捌’ (ba1) = Disentangle This ideogram - (in its Chinese interpretation) can mean ‘eight’ - an alternative form of ‘八’ (ba1). A ‘hand’ which expertly uses a ‘knife’ - cuts through the flesh and bones of a fish so that it is separated into ‘eight’ clean parts (probably a generic term meaning ‘many’). There is also the central idea of ‘disentanglement’ - so that no unnecessary error (or resistance) is met. This is because ‘entanglement’ means ‘hindrance’ - and the skill referred to here involves the ‘avoidance’ of such self-imposed difficulty. Evading ‘resistance’ is the correct path that leads to such a skill. The blade of the knife skilfully feels its way around (and along) the natural contours of the bones – and does NOT cut directly (at right-angles) into the bone-structure at any time. There is a ‘going with’ rather than a ‘going against’. This ideogram is the central element of this Karate-Do principle - and probably means slightly different things within the various styles which make use of it. 3) き(Ki) - Japanese Equivalent of Chinese ideogram ‘幾’ (ji3) = Skill There is an indication of ‘quantity’, ‘measurement’ and ‘refinement’ within Japanese language dictionaries. The suggestion is that the correct manipulation of exact amounts is a great skill which has to be mastered in any successful avenue of life. This idea spans both the material and the spiritual world! An individual can carefully follow the established criterion laid down by those who have gone before – or if such an individual possesses the correct (and right) amounts of psychological insight and physical strength – then they might set out on their own path and become an inspiration for those who are to come! Conclusion: Meaning When taken as an integrated whole – the martial principle of Tai Sabaki (体捌き) suggests that the physical body (its central core and not just its periphery) is skilfully used (manipulated) in a combat situation so that there is no direct conflict between the defender deploying this technique - and an attacker ignoring this technique. Tai Sabaki (体捌き) is NOT just the skilful movement of the arms and legs in ‘protection’ of the central core (the torso). Tai Sabaki (体捌き) is a ‘centre-out’ technique that requires the core and periphery to work in concord. Strength does not clash with strength. The ability to assertively ‘give-way' is the key to this technique. Indeed, when the timing is perfect - ‘giving-way’ becomes far stronger than the momentary strength associated with a dramatic (but short-lived) show of strength! Giving-way, at its highest manifestation, not only ‘absorbs’ and ‘nullifies’ ALL incoming power – but when performed correctly, generates the basis for ‘greater’ power to be produced that is not reliant upon linear (muscular) strength – but rather the ‘circular’ movement associated with the structures of the bones and joints! The bodyweight ‘drops’ into the ground through the shaft of the (aligned) bones and rebounds upwards through the centre of the bone-marrow – producing a seemingly endless supply of ‘muscle-free’ power! As this power is greater than that associated with the muscular ‘tension’ of thuggery – the defender occupies a unique time-space frequency within which the attacker cannot access (or penetrate) regardless of the willpower exhibited. The linear attacks cannot land on an object continuously moving in perfectly timed circles. Once such a level of mastery is achieved – the defender can decide the level damage perpetuated upon the attacker depending upon circumstance. Should the body of the attacker be temporarily or permanently disabled? Should the body of an attacker be only (gently) nullified as if in play? Someone who has mastered Tai Sabaki (体捌き) possesses all these choices. This is why the Wado Ryu Style of Karate-Do posits the highest ideal of a defender possessing the ability to prevent damage to both their own body AND the body of the opponent! An ideal of the highest nobility!

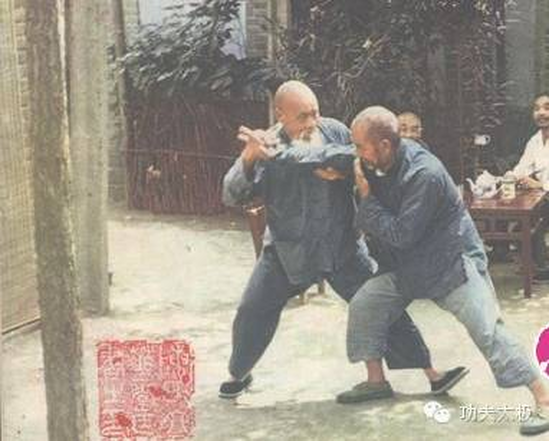

The profound level materialises after years of training and ripens with age. It looks and feels very different to the manner in which other martial arts manifest and are manifested. It has more in common with Daoist martial expressions – but is reliant upon Buddhist mind expanding practices. There is a deep sense of peace emanating from within a profound and limitless void. Power manifests – and fades away in a cyclic motion. There is no rush and yet the power manifests according to the urgency of need – as if the required power is being extracted from the surrounding material conditions as the need arises. This lack of urgency coupled with the immediacy of the required power gives the false impression that a) nothing is happening and b) nothing will happen. These false impressions flash across the surface mind of the opponent and then there is the blinding flash as the power hits home. As there is the minimum of conflict – the highest levels of attainment seem very different to the more commonly available martial arts. Nothing is happening and yet everything is unfolding. Years of preparation generate the maximum conditions that dissolve as their function is performed. This process can repeat itself as many times as is required and in as many different ways as is needed. Winning is not the objective – but rather a cyclic survival. The feeling of a deep and permanent peace is similar to floating in space free of a gravitational pull and yet gravity is fully mastered and is under complete control. Seeing beyond that which needs to be created is the essence of being nowhere all at once. Freedom is a lack of artificially imposed barriers that have no place during the birthing or dying processes. Being at one with the empty mind ground is to be at one with empty space in all places and at all times. The mind expands because these (inner) false barriers are removed. As these (inner) false barriers are removed – there can be no (outer) false barriers. This reality is devastating for the opponent to encounter and ‘healing’ for the practitioner to attain.

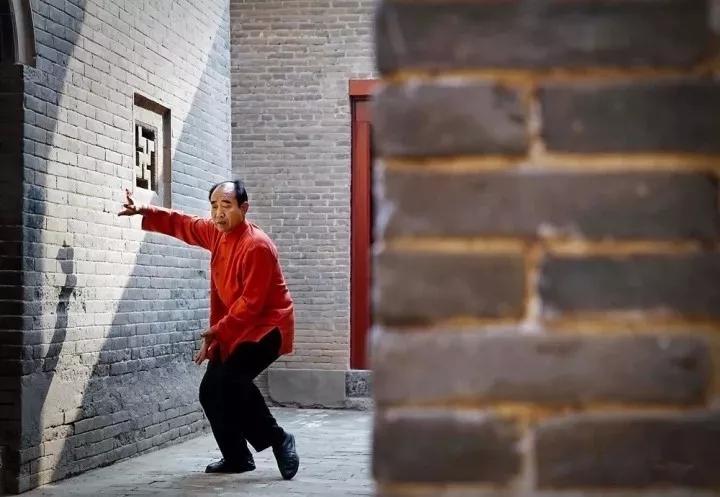

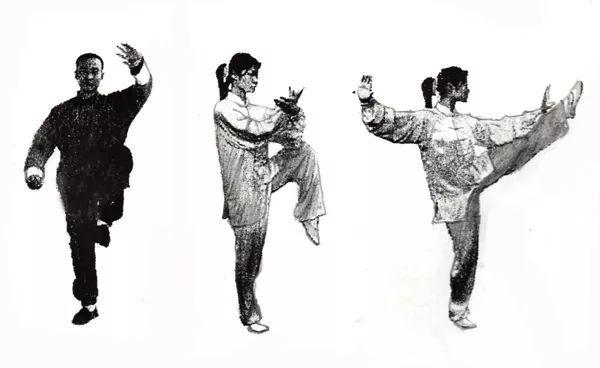

Critically Examining the ‘Fist Frame’ (拳架-Quan Jia) as the Foundation of Taijiquan Practice11/27/2021 Contribution & Translation Shifu Adrian Chan-Wyles Beginners learn Taijiquan by replicating the "fist frame" (拳架-Quan Jia) - or the ‘physical structure’ of the Taijiquan style as taught by their teacher. The teacher uses the ancient method of teaching one step and one sequence at a time, so that each student can learn each step and each sequence before moving on to the next section. The teacher ‘expresses’ each movement one by one, whilst the practitioner imitates these movements ‘one by one’ until they become natural. This process is termed the "leading frame" (领架 - Ling Jia). Although the “fist frame” defines the physical appearance of the Taijiquan style, the essential and underlying reality of these movements contains an extremely rich content. It not only contains its extensive martial application, but this body of knowledge is closely connected to the internal strength-building (内功 - neigong) exercises. Authentic Taijiquan is passed on from one generation to the next through its readily recognisable ‘fist frame’ or stylised form. It is only through the correct preservation of the “fist frame” that all the other ‘hidden’ techniques are preserved and passed-on. To effectively learn a style of Taijiquan, you must first seek out the correct “enduring image” (形象 - Xing Xiang), as taught by a reliable teacher. Logically follow the rules, be meticulous, and replicate each movement one by one and step by step. First learn the correct orientation of the body (that is, the correct alignment of the head, torso, arms, legs, hands and feet, etc), next perfect the hand positions and the techniques through which these positions are used, then perfect the footwork – learning ‘how’ and ‘when’ to step and stand-still, learn all the movement routes – that is how to step, when to stop stepping and how to piece each movement together into a smooth sequence of events, and through doing all this probably, mastery the ‘outer’ style of each style. The ‘outer’ methods are mastered first – then followed by a deepening of understanding and awareness whereby the ‘inner’ methods become apparent and are in-turn mastered. This creates a unified process which sees a relaxed mind, body and environment ‘merge’ into one complete reality of ‘awareness’ and all-embracing ‘presence’. According to whatever the style of Taijiquan being studied, ensure that the ‘chin is placed-forward (and slightly down) so that the vertebrae of the neck are gently but firmly ‘extended’ and the head correctly ‘lifted’ and placed with a ‘rooting’ strength upon the shoulders. The head and neck – in relation to the shoulders – becomes both ‘buoyant’ and yet ‘heavy’ whilst being perfectly aligned between all its constituent factors. This alignment of the vertebrae extends down from the neck into the chest and lower back area (simultaneously confirming the ‘concave’ and convex’ anatomical structures), with each placed exactly where it should be above and below all other contributing structures. The shoulders are ‘rounded’ as they surround the ‘rounded’ chest-cavity and there is no contradiction in the head-to-toe alignment of the bones, muscles, ligaments and tendons. The chested is rounded as it fills and empties with ‘air’ and ‘qi’ (氣). Therefore, the concave and ‘empty’ chest (together with the relaxed and strengthened abdominal muscles) joins the neck and head in being both ‘robust’, incredibly ‘strong’ through ‘alignment’ and yet ‘flexible’ like the wind. The pelvic-girdle is correctly aligned with the vertebrae that emerge from it. The pelvic-girdle form a ‘bowl-like’ structure into which the mass of the digestive organs sits, manoeuvre and function, etc. From the pelvic-girdle the upper body is structured and lower body touches the earth. The pelvic-girdle connects to the ground through the bone, joint and muscle structures of the legs, which always includes the connecting tendons and ligaments all over the human body! The pelvic-girdle must be rounded and concave so that it aligns with the knees, and the ankles, whilst the knees remain ‘rounded so that the bodyweight can ‘drop’ and ‘rise’ through the area unhindered. The descending bodyweight drops into the ground through the centre of the anatomical foot-structure (which varies in exact location depending upon the technique being used). When all this is ‘corrected’, then it becomes obvious that the shoulders and hips, elbows and knees, wrist and ankles and hands a feet become permanently ‘unified’ and ‘aligned’ in their physical activity and non-activity (I.e., ‘standing still’, etc). As ‘awareness’ increases, the shape of the hand and the ‘exact’ placement of one bone to another becomes possible and is a skill repeated all-over the body including throughout the structures of the feet. In other words, the ability to ‘align’ and correctly ‘arrange’ the entire body in general – becomes a highly efficient ‘localised’ skill applied to the smallest area of the body itself. This is how tremendous power can be generated throughout the ‘frame’ and correctly emitted through with a ‘fist’ or the open ‘palm’. Conversely, huge amounts of power can be ‘absorbed’ through an ‘open’ or ‘closed’ hand, distributed throughout the Taijiquan ‘frame’ and harmlessly neutralised into the environment. This is how the ‘mind’ first ‘expands’ its awareness’ throughout a ‘unified’ body-structure (or Taijiquan ‘physical ‘frame’) before ‘expanding’ beyond the physical ‘frame’ and becoming ‘all-embracing’ and ‘all-inclusive’ of ‘all’ and ‘nothing’ in the physical environment! This is the process of how a material ‘form’ (形象 - Xian Xiang) become an immaterial, ‘mind’ or spirit-driven ‘form’ (神象 - Shen Xiang). If ‘physical’ Taijiquan practice does not evolve into a ‘spiritual’ Taijiquan practice, then a life of practice, determination and sacrifice has been entirely wasted! The teacher provides the ‘fist form’ - but you must practice ‘beyond the ‘fist’ and firmly cultivate the ‘mind’. Without this transformation, nothing substantial can be fulfilled. The ‘spiritual essence’ is contained within the ‘form’ and the ‘frame’ - but is dependent upon neither and must emerge from both. However, due to the nature of the complexity of Taijiquan design and practice, it is inevitable that some will encounter problems with their practice. Beginners are often prone to rigidity of mind and body and are unable to properly ‘adapt. The most common errors involve ‘stiffness’ (僵 - Jiang), ‘scattered’ awareness (散 - San), ‘discontinuous’ awareness (断 - Duan), ‘non-alignment’ (歪 - Wai), ‘non-rootedness’ (浮 - Fu) and other problems. A) ‘Stiffness’ (僵 - Jiang) - involves ‘tension’ being hidden throughout the mind and body of the practitioner. It is a product of ‘habit’ that must be undone and countered through the practice of psychological and physical relaxation. Habits of thought that generate psychological tension must be ‘dissolved’. Simultaneously, the tension that abides within the muscle-fibres must also be ‘released’ through deep breathing and the focus of the mind’s attention upon the area. Eventually All mind-body tension (which is merely ‘blocked’ qi energy flow), must be a) ‘released’ and b) ‘reabsorbed’ into the entire mind-body system. B) ‘Scattered’ awareness (散 - San) consists of a mind that is not yet ‘unified’ into a spiritual-whole so that the physical body is also affected by this ‘disunity’. A scattered mind inevitably manifests as a scattered body in the physical realm, whereas a unified mind which is all embracive of the physical body (and environment) inevitably provides the foundation for a fully united Taijiquan form. The ‘awareness’ must be ‘united’ by focusing the mind and disciplining its functionality. Once the psychological processes are ‘united’ - then the physical body (and its actions) will be permeated by this ‘unified’ awareness. C) ‘Discontinuous’ awareness (断 - Duan), between the upper and lower body, means that there is no connection between the mind, body and environment. In other words, no ‘rootedness’ as the practitioners ‘awareness’ capacity is both incomplete and discontinuous. The upper and lowe body cannot interact in a fluid and smooth fashion. Q energy flow is ‘broken’ at crucial points (effecting ‘jing’ [精] and ‘shen’ [神] circulation, generation and transformation). As the top half of the body is ‘disconnected’ from the bottom half of the body – there is no transference of ‘awareness’, ‘energy’ or ‘ability’ through the pelvic-girdle. Beginners must observe and understand flowing water, reeling silk and clouds floating across the sky and how nature achieves these feats of action with no apparent effort at all. Human-awareness must extend fully in the ten-directions and not stop short at nine-directions! The practitioner must master the connection between ‘awareness’ and ‘movement’ - when such an awareness is ‘lacking’, then there is a ‘discontinuous’ awareness, or ‘break’ between areas of psychological and physical control. This problem can be resolved through practicing ‘deep’ relaxation of mind and body, as well as focusing the mind to ‘lead’ and ‘guide’ (引 - Yin) the awareness evenly through the physical structures of the body, so that ‘awareness’ always precedes and initiates all movement so that there is never a ‘break’ between ‘intention’ and ‘actuality’. D) ‘Learning to lead’ (引 - Yin), or direct a strengthened, concentrated and united mind so that its ‘intention’ continuously precedes all movement both ‘within’ and ‘without’ the physical body. In this regard, conscious awareness must automatically permeate the ten directions and everything within those ten directions – including the individual mind and body. This is a continuous pulsation that exists during sleep and awake times and which is fundamental and underlying in nature. Guiding the awareness, however, ss subtly different as it is a ‘refined’ awareness operating within this meta-awareness. Whereas the meta-awareness permeates the cellular structure of the mind and body – this ‘leading’ awareness penetrates the cellular wall and permeates into the subatomic structures. It has within it a compelling and attracting force which can also be ‘reversed’ into a repelling force (like releasing the built-up energy in a drawn-bow). At other times, it directs awareness and ‘pulls’ the physical body into the various directions of movement required. It is nothing short than the evolutionary mind-body nexus. ‘Thought’ within this context, although appearing ‘spiritual’ and ‘other-worldly’ is in fact a very subtle form of substrative material reality. E) ‘Non-alignment’ (歪 - Wai), refers to a disjointed and misplaced Taijiquan ‘frame’ (positioning) and ‘sequencing’ (form) so that the entire manifestation departs from the ‘law’ of the style, the philosophy of the tradition and the instruction of the teacher. Another description is that of a ‘crooked’ mind and body which mislead the practitioner and the world of taking the wrong direction. The body leans when it should be straight, or is straight when it should be leaning! The body remains ‘unrooted’ when it should be firmly affixed to the ground. The mind has no unified presence and is unable to penetrate and guide the the physical structures of the body. As there is no penetrative insight, the movements are ridiculous and disconnected. There is no awe-inspiring presence and no real Taijiquan practice taking place! F) ‘Non-rootedness’ (浮 - Fu) can also be translated as ‘floating’ and refers to the non-dropping of the ‘qi’ (and ‘bodyweight’) down into the dantian (丹田) situated two-inches below the naval and through the centre of the bones (stimulating the bone-marrow) in the case of the bodyweight proper. Pockets of psychological and physical tension can prevent the qi-energy flowing properly through the eight special channels (and the numerous other major and minor qi-energy flow channels), as well as the bodyweight ‘dropping’ effectively through the centre of the bones down into the floor through the soles of the feet, etc. Eventually, the dropping of the bodyweight results in a ‘rebounding’ force which bounces the qi-energy back up the body through the centre of the bone marrow – a gravity related processes which eventually integrates with the qi-energy flow through the qi-energy channels. If an underlying psychological awareness of the deep structures of the body is not present, then neither qi-energy flow nor bodyweight movement will be understood or even known to exist! Instead, the external body will be separated into essentially top-heavy and insular compartments of disjointed and non-rooted entities! All is disconnected from the ground and from the awareness of the mind. Drop the awareness into the ground to rescue the mind and body from this hellish existence! This is why the ‘fist frame’ is the mother of the Taijiquan system of advanced Chinese martial arts (as it conveys the ‘secret’ of how to ‘punch’ with extreme power! Each individual part of the body must be thoroughly penetrated and minutely understood with a fully develop and directed conscious mind – before each part of te body is ‘integrated’ (through accumulated ‘insight) into a ‘unified’ whole. Although a ‘form’ of Taijiquan made well hold continuous physical characteristics that continuously broadcast a well-known' style – it is the mastery of the ever-change ‘frame’ of the Taijiquan form that is vital for martial arts dominance and success in the physical world. Of course, the ‘form’ and ‘frame’ obviously over-lap and coincide but they are not identical. Whereas a ‘style’ of Taijiquan may well utilise a continuous ‘form’ or philosophical-physical approach – whilst a continuously changing, altering and adjusting ‘frame’ may be manifested by an expert practitioner. Whilst being firmly ‘rooted’ to the nourishing ground, an expert practitioner of Taijiquan is continuously manifesting the ‘root’ principles of the style, whilst also adjusting that particular ‘form’ (physical superstructure) to the conditions prevailing in the external world. A ‘fist frame’ facilitates ‘punching’ (or ‘open and closed hand techniques’ in general), whilst a ‘kicking frame’ opens the hip-area allowing for an array of ‘lifting’ or ‘floating’ leg techniques which uses the foot, knee or side of the leg-structure to ‘strike’ or ‘block’ whist standing still, or moving forward, back or side to side (although some of this activity might fall under the designation of a ‘stepping frame’ adjustment). An advanced ‘iron-vest’ frame allows for the bone structure to be utilised in a manner that deflects, absorbs or re-directs incoming energy, etc. There is even the case that suggests that the ‘frame’ of a Taijiquan style should be further adjusted as the age of the practitioner increases to counter the effects of ageing. With regards to self-defence, the body-shape, experience and motivation of an opponent will call upon the defending Taijiquan to adjust the type of ‘frame’ they manifest during hostilities. A Taijiquan ‘form’ that does not adjust its ‘frame’ (or the distance between the feet and between the hands), is then ‘stuck’ in manifesting just one particular ‘frame’. This is a common mistake today developed from a lack of properly qualified teachers. When Taijiquan was ‘liberated’ from the limitations of feudalism in 1949 – there was not readily available a suitable cadre of instructors to carry-out this advanced ‘liberating’ policy. To remedy this, it was decided that initially it was enough for the ‘copying’ of the superficial movements (I.e., ‘form’) to take place throughout China, and that over-time, as this new approach of ‘openness’ settled in (with a limited single ‘frame’), the number of qualified teachers would increase. Today, this transitional stage Is still in operation, with practitioners seeking an ever-greater depth of understanding, although association with legitimate lineage masters that are coming to light. This is a slow but inevitable process. Taijiquan – the most advanced martial art ever constructed by the human mind – has been ‘freed’ from the few exclusive lineages that once controlled its dissemination. Although lineages till exist and their practice is disciplined, the knowledge they possess in now viewed as belonging to humanity. Chinese Language Reference:

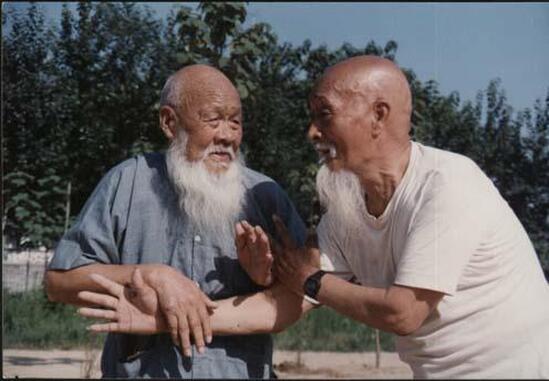

https://www.sohu.com/a/114000920_467831 拳架为学练太极拳之母!练拳易犯的几点坏毛病,快来看看自己有没有? 2016-09-09 11:29 点击上方↑"功夫太极"快速免费订阅太极养生资讯 "拳架"为学练太极拳之母[摘编] 初学太极拳应从学习“拳架”开始。即是学练老师的拳架。一招一式,逐一模仿。这一过程,称之为“领架”。拳架虽为外形,但却有极为丰富的内容。它不但含有很多技击招式,还与内功练习紧密相连。拳架是太极拳的基础,也是练习太极功夫的向导。没有拳架就无法练习太极拳。架子正确与否关系到太极拳的功夫能否练成。 学练拳架,先求形象,须循规蹈矩,一丝不苟,逐一模仿。先学基本的身法、手法、步法,动作路线,各定式的样子及要领。架子应先求开展,后求紧凑。要求全身节节放松。如某一定式,先查是否“虚领顶劲,立身中正”,是否“含胸拔背,胸空腹实”,是否“松腰落胯,圆裆扣膝收臀”;再查步法是否正确;再检查肩肘腕是否放松,是否“沉肩坠肘、塌腕舒指”;最后再检查掌形、拳形,钩手等是否正确。在“形象”的基础上再求“神象”。不但要求形象,还要求神象。如不得太极拳之神形,则练一辈子也是茫然,不成大器。若想精其技,趋大成者,非得老师拳架之神形不可。然而,由于太极拳的特点,初学者往往难以适应,易出现一些毛病,最常见的主要有:僵、散、断、歪、浮等毛病。 1 僵 就是僵硬、松不下来。练习太极拳,松为第一要义。而没有经过太极拳练习的人,身上都有僵劲。年龄越大,身体越是强壮,僵劲越大。而太极拳的动作是圆的运动,要求柔和缠绵,节节贯串,全身协调,主宰于腰。这就给练习太极拳带来很大的困难。因此,一开始,就要强调放松,练习者要有意识地使自己的身体放松。用意不用力,意松体松,内外皆松。 2 散 即神散,形散。练习太极拳要求全神贯注,心无旁骛,如果练拳时心不在焉,杂念丛生,就无法做好动作。形散一般是指动作幅度过大,没有含蓄,或者动作不协调,散了架子。练习太极拳手臂和腿要自然弯曲,不可直手直脚,要注意处处保持太极球的形态。同时注意全身的协调性,所有的动作主宰于腰,以身领手,周身一家。 3 断 指意断,劲断。动作不连续,上下动作之间断开,缺乏圆滑的过渡。太极拳要求柔和缠绵,练拳时,上动未停,下动又起,如行云流水,抽丝挂线,一气呵成,动作做到九分,意要贯到十分。而初学者往往不能很好掌握动作与动作之间的衔接问题,因此,就出现了“断”的问题。要克服这个毛病,一要注意放松,二要加强“引”的练习。即掌握“引”的规律,一般来说,引的规律是欲上先下,欲左先右,欲前先后。就是向相反的方向运动。 4 引 “引”在太极拳中有非常重要的作用,它是太极拳的精华和绝妙之处。它不但起着承上启下的作用,还关系到太极拳阴阳转换,虚实开合的变化。没有引,太极拳的动作就无法圆滑过渡;没有引,就无法实现折叠转换;没有引,劲就无法绵绵不绝。 然而,在现实生活中,许多太极拳练习者,往往忽视“引”的练习和应用。他们往往注意动作的外形是否到位,样子好不好看,而忽视了太极拳的精华。练好引的关键是用内动带动外动,心静体松,精神内固,丹田旋转,引领全身,以根节催动梢节,动作似停非停,将展未展之际,心意一动,“引”则油然而生。上动未停,下动又起,流连缱绻,无始无终。应该特别指出,引是自然而然的,是松沉的表现,不是故意做出来的。不可为了做引的动作,故意把拳打得一顿一顿的。引从外形上看,以不露痕迹为上品。 引在推手中有着极其重要的作用。两人接手后,轻轻一引,即可化解来力。能引,则能做到劲由内换。由于引的圈子很小,则可做到在不动身形的情况下化发自如,即引即发,原地风光。 因此,打太极拳需注意引的练习。只有把引练好了,才能打出太极味,才能使整套拳如抽丝挂线,绵绵不断;似长江大河,滔滔不绝。引是太极拳的细微之处,乃太极拳绣花之法,须默识揣摩,细心体悟,才能真正学到。 5 歪 指身法不正。前俯后仰,左右歪斜。练习太极拳身法以端正为本。身法端正,无所偏倚,虚灵内含,浩然之气,运于全身。初学者往往由于动作僵硬,易使身体不正。身法中正是练好太极拳的基础,千万马虎不得。 6 浮 即漂浮。太极拳要求含胸拔背,胸空腹实,气沉丹田,落地生根。而初学者往往架子忽高忽低,挺胸突臀,动作漂浮,气向上涌,头重脚轻。浮乃练习太极拳之大忌,须注意克服。 要克服上述毛病,关键要抓住“松、静、沉”三个字。无论练习何种太极拳,都要在这三个字上下功夫。因此,“松、静、沉”为练习太极拳的三字经,要把它刻在脑海中,落实在行动上。在学习老师拳架的过程中,要细心模仿,悉心领悟动作要领,发现问题及时纠正。太极拳架中包含有极丰富的内容,要掌握这些内容,需要长期反复练习才能做到。 因此说,拳架为母。练习太极拳一定要在拳架上下功夫。每天反复盘拳架,如有可能,尽量多练。同时,要不断领悟内在的东西,练悟结合,“拳打千遍,其理自现”。练习拳架有一个“从外引内,以内带外”的过程。开始时,只能外形划大圈,而后逐步产生内动,每个动作先有内动,再有外动,环环相扣,无始无终,动作沉稳,柔棉,一动无有不动,一静无有不静,内外合一,周身一家。只有这样,才能逐步提高自己的太极拳水平。 孔子曰:“人而无信,不知其可也” 意思就是说:一个练武之人要是连《功夫太极》微信都没关注,简直都不知道他是怎么练拳的.. Foundational Taijiquan is practiced by those with health or mobility issues. This is a gentle set of physical movements designed to get a person moving around in a dextrous manner. Taijiquan can be very useful for those who are not fit and need some type of co-ordinated physical movement combined with deep and full breathing. With repetition this training process can build strength in the legs, improve balance and dexterity, and enhance the circulation of oxygen throughout the body by relaxing any and all unnecessary muscular tension. Through aligning the bones (and dropping the bodyweight into the ground), the bones, joints, ligaments and tendons are made more ‘robust’ through correct weight-bearing! Many people spend years working on this practice and quite often gain a considerable suppleness through this relaxation and the sharpening of ‘awareness’ in the mind! For many practitioners in the West, Taijiquan is encountered only later in life, and quite often is not the common spectacle it is in China and throughout many diasporic Chinese communities. The popularity of basic Taijiquan (even in China) relies on quick courses which involve a ‘coach’ who has learned a Short Taijiquan Form over a six-week time period and is then tasked with conveying these movements to two or three classes of students a few times a week! This approach certainly gets the basic techniques ‘out there’ and gives dedicated individuals a training platform which they can build upon at a later date. This can involve longer and more complex Taijiquan Forms (of which there are many Styles), and can even include competitions, seminars and demonstrations, etc. However, even if this type of practice results in winning a World Title for ‘moving about effectively’ - this is still not the complete Taijiquan practice. If you want to master the proper and in-depth practice of Taijiquan, you will have to find a genuine gongfu Master who is knowledgeable in Daoist self-cultivation technique and knows how to ‘fight’ in real life without compromising the sublime spiritual vision that underlies the Chinese martial arts. Following decades training with Master Chan Tin Sang (1924-1993) - I now occasionally have the honour of meeting the odd male or female Taijiquan Master through ‘invitation’ so that my physical and spiritual understanding of Taijiquan can be ‘tested’ and ‘confirmed’. Such encouragement ‘dissolves’ difficult to see ‘habitual blocks’ in the mind and body and moves onward or deeper into penetrating the empty essence of the Dao – as all movement is equally ‘empty’ and ‘still’ - this is why an immense power emanates through the channels that connect the ‘broad earth’ to the ‘divine sky’. This is why every perfect technique is both immensely ‘powerful’ and equally ‘empty’ from beginning to end – and within this freedom is vibrating a positive light that is a combination of wisdom, loving kindness and compassion for the entirety of existence! Advanced Taijiquan is a product of a perfected state of mind and body that expresses the perfect Taijiquan technique – but which is no longer ‘limited’ to the practice of the physical Taijiquan Form - which naturally manifests every moment of everyday, whether formally training, lying in bed, going to the toilet, meditating, making love or carrying-out your work! As many of you reading this either have a low opinion of Taijiquan or believe Taijiquan cannot be used for combat (viewpoints that are a product of a lack of direct cultural knowledge), the manner in which Taijiquan technique is used on a kick-bag is simple and straightforward. Advanced Taijiquan expresses the entire ‘bodyweight’ through any part of the body without any undue effort. Just as the bodyweight ‘drops’ into the ground through the aligned bone-structure – a re-bounding force naturally rises up continuously and without a break in the circuit. This remains true just as long as a practitioner is stood within a strong gravitational field. I start a suitable distance from the kick-bag and carry-out a mini-form set of co-ordinated movements that brings my body nearer the kick-bag and sets-up the power-technique! Today, I started with the left leg forward and threw on the spot a left-lead punch, right-reverse punch and left-lead punch. Weight shifted back onto the reverse right-leg (with bent left-leg forward in ‘cat stance’) and I throw a front-snap kick – landing forward on my properly placed left-foot and bringing the weight onto the left-leg. The power-shot is the reverse right roundhouse-kick – which swings through the air and impacts the bag with considerable and unhindered power! The process is repeated on the other side of the body and I repeat this for three-minutes. Any combination of techniques can be used that test the ‘smoothness’ of Taijiquan technique on the one-side – and the unbroken (and considerable) power on the other. Obviously, being ‘rooted’ is important as is continuously changing sides so that left and right are properly trained and tested (as true combat is unpredictable unlike fighting with rules during sporting encounters). The mind should be calm, still, aware and all-embracing so that it is ‘reflective’ of all phenomena (like a mirror). The Buddhist Surangama Sutra explains this principle, as do various Daoist texts such as the Laozi and Zhuangzi, etc, and the ‘Book of Changes’ (Yijing). Not everyone is trained to this depth of Taijiquan attainment, and not everyone wants to be trained to this degree – but it is an option with the proper training and instruction.

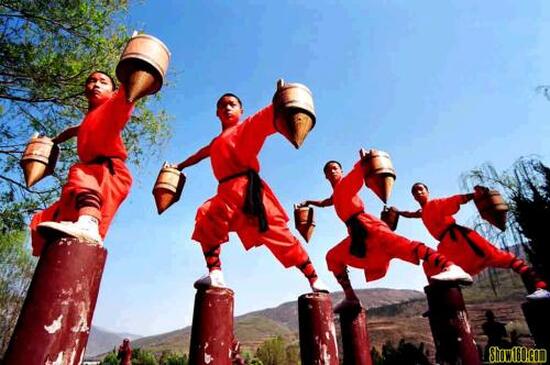

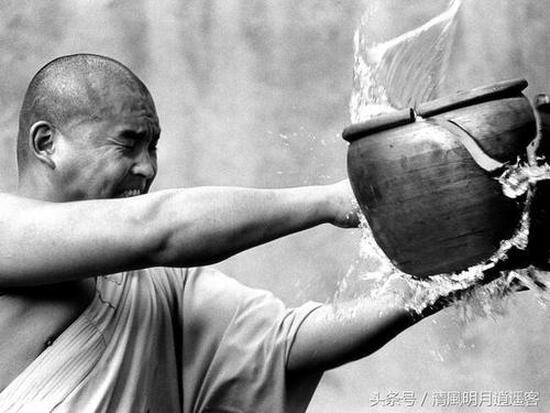

Advanced martial arts practice is ethereal even though it involves the movement of the body. In fact, moving the body is basic gongfu training, a mastery of which should be gained in one’s youth if possible. When the body ‘ages’ - a practitioner does not want the problem of mastering martial technique whilst coming to terms with how ‘ageing’ changes the mind and body. Knowing how to stand, fall, get-up, moving, kick, punch, block and evade, etc, are foundational issues that must be thoroughly absorbed into the deepest levels of the mind and body well before middle-age is reached. Of course, this is not always the case, as some people take-up the practice of traditional Chinese martial arts late in life – but with regards the more robust and rugged ‘external’ techniques – youthful practice is preferred. This is why many older people (with no previous experience) start their martial arts training through one of the ‘internal’ arts – which are a product of an ‘advanced’ and ‘mature’ mind-set. On the other hand, if an individual is able to build 20-30 years of training prior to hitting 40-50 years of age – then the bones, joints, muscles, ligaments, tendons and inner organs have all had time to experience a ‘hardening’ process over-time - and are far more ‘robust’ whilst the individual traverses into older age. Probably the greater reason for early martial arts practice is that the ability to produce massive (internal and external) impact power (with minimum) effort must be mastered before the body transitions into older age. This observation does not mean that older people cannot achieve this ability later in their life – but to already possess this devastating power is one less burden – particularly as we may also have far more responsibilities as mature people than the average young person. However, with the right type of instruction from a genuine Master, anyone of any age can ‘master’ gongfu regardless of circumstances. Motivation is the key to it all. The mind must be ‘still’ and ‘expansive’. Its psychic fabric must be simultaneously ‘empty’ and yet ‘envelop’ all things without exception! Although there is much experimentation in the West with the physical techniques of the many (and varied) gongfu styles – very few practitioners are interested in the spiritual or higher psychological aspects of traditional Chinese martial arts. This is because gongfu has been taught the wrong way around in the West to suit the cultural bias of the fee-paying audience. Whereas in China kicking is learned before punching – in the West punching is taught before kicking (because of the influence of Western Boxing). Whereas in China a gongfu practitioner learns to stand still and to stand ‘solid’ whilst defending the ten directions – in the West students are taught to move around before being taught how to ‘stand still’ (this is because Western students do not understand the important of achieving inner and outer ‘stillness’). Whereas in China gongfu student learn to ‘relax’ before assuming postures – in the West students are taught to ‘stretch’ using yoga-like techniques (mostly unknown in China). Whereas students in China learn to ‘strike’ various wooden objects to condition the bones of the hands and feet – in the West, students are encouraged to hit ‘soft’ pads that give a false impression of what it is like to hit a ‘real’ body! In the West, the mind is ‘entertained’ as a means to secure continued fee-paying through class attendance – whilst in China the Master continuously looks for new ways of ‘testing’ the virtue of the student and for any reason to ‘expel’ them from the training hall! All this ‘inversion’ must be remedied if the highest levels of spiritual and physical mastery are to be achieved. This has nothing to do with rolling around on a padded floor wearing padded-gloves – and everything to do with ‘looking within’ to refine the flow of internal energy. The awareness of the mind must permeate every cell of the physical body whilst the practitioner sits correctly in the meditation posture. What else is there? When advanced practitioners ascend to a certain age of maturity, reality has nothing to do with the ego pursuit of ‘winning’ or ‘losing’ in petty disputes that ultimately mean nothing. Most of the combat sports of the moment are fleeting and exist merely to make money – and they are ineffective on the modern battlefield and not practiced by the military! The final lesson is to ‘leave the body’ with the minimum of fuss when the time presents itself. In a very real sense, a genuine Master of martial arts has ‘already’ transcended the boundaries of material limitation whilst still living. This sense of ‘completion’ and ‘transcendence’ is what draws the already perceptive into his or her presence to receive instruction...

After spending a year in education in Reigate and Redhill – where I studied Wado-Kai – I then relocated to Hereford to continue my education. Master Chan Tin Sang (1924-1993) - my Hakka Chinese gongfu master (and eventual relative through my marriage to a female relative) - had granted me permission to carefully select a local martial art (but only one at a time) and dedicate myself to its study. As Chinese gongfu was rare in the UK in those days – at least in public (although it had a vibrant presence behind closed doors and within family lineages) - it was generally thought that I would encounter mostly Japanese karate – but with each lineage having its origins within China at some point in its history. This turned-out to be a logical assumption. I had gained an ‘Orange Belt’ (7th Kyu) in Wado Kai. I first attended a Wado Ryu class in the centre of Hereford which had an instructor who wore a black gi top with white trousers whose attitude was superficial and intentions entirely mercenary. This style (and class) lacked the integrity of what I had experienced in Wado-Kai. He would not let me keep my grade and as I did not trust him, I declined his offer of starting again. I then discovered the Shukokai karate class held at Hinton Community Centre, in Ross Road, Hereford. As Sensei Tom Beardsley – the instructor – allowed me to keep my grade, this place would be my training home for the next two years or so. There was then one small (but warm hall) to the left of the main door, and a much bigger (but eternally cold) hall to the right. We trained mostly in the smaller hall, with special training days at weekends attracting far more people from all over the UK being held in the bigger hall (often with the highly ranked Eddie Daniels visiting, I think from Birmingham). In those days, this style was headed by O Sensei Kimura Shigeru (10th Dan) [1941-1995] originally from Japan – whom I trained-under in the late 1980s at a large training symposium held in Poole, Dorset. (If I remember correctly, the karate class travelled from Hereford to Poole on a specially hired coach). Like ‘Wado Ryu’, the Japanese term ‘Shukokai’ is written using the traditional Chinese characters of ‘修交会’. In the Chinese language this is pronounced ‘Xiu Jiao Hui’ and translates into the English language as ‘Cultivation - Gathering to Learn and Exchange – Association'. As Hereford, (at least in those days, was like a smaller version of London), is vibrant and cosmopolitan, the Shukokai classes attracted men and women, old and young and people from many different ethnic backgrounds. Some members were serving or former members of the British Army – including the Special Air Service (SAS). Some young men from Hereford were also members of ‘R’ Squadron (‘R’ standing for ‘Reserve’), of the local 22nd SAS Regiment. I trained alongside a man named ‘Robin’ who had been part of the SAS counter-terrorist raid at the Iranian Embassy in London in 1980, etc. The class was expertly guided by Sensei Tom Beardsley (then a 3rd Dan). The Shukokai style (which has its roots in the Okinawan karate style of Shito Ryu), emphasised the generation of power through correct postural alignment and the robust use of the hip twist. This is not unique to this style, but in the 1980s, Sensei Kimura had developed this principle to a very fine art, whereby a student could be taught to harness their bodyweight and direct it through their hip twist into every conceivable karate technique, be it a punch, kick or a block, etc. Although the basis of many internal and external Chinese gongfu styles, O Sensei Kimura in many ways demystified this process and made it far more accessible to ordinary people. Westerners did not have to commit themselves to the spiritual aspects of the Asian arts, as O Sensei Kimura presented this teaching in a distinctly ‘modern’ and ‘secular’ manner. However, in the two years that I was present, I witnessed the style alter radically as its technique was continuously adjusted (week by week) to make the kata look more likely to ‘win’ competitions. As the style moved away from its traditional underpinnings, inevitably many of its students left. Not long after I left (with a group) in 1986, I was told that the style had left the Hinton Community Centre and had become a totally different entity. If I can locate my old Shukokai karate licence, I will photocopy this document and place it on this blog post. I learned a tremendous amount about ‘politics’ in the martial arts at this time in my life. As a traditional martial artist, I have no interest in grades, competitions or self-advancement. These things were incidental to my learning experience.

|

AuthorShifu Adrian Chan-Wyles (b. 1967) - Lineage (Generational) Inheritor of the Ch'an Dao Hakka Gongfu System. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed