|

The Island known as ‘Okinawa’ lies off of the South-West coast of Japan - forming part of the Ryukyu Island Chain - and is expressed in Japanese (Kanji) ideograms as ‘沖縄’. This name may be deconstructed as follows: a) oki (沖) = expanse of open water b) nawa (縄)= rope or thread The name appears to be a direct description of the numerous islands that comprise ‘Okinawa’ – which are themselves a substantial (Southern) part of the larger Ryukyu Island Chain. Perhaps the geographical placement and general shape of the islands was seen from high mountain-tops, surveyed in passing ships and/or observed from upon high by those who flew in the ‘Battle Kites’ known to exist within medieval Japan. Whatever the case, the Okinawa Island Chain is said to resemble a meandering rope lying across the surface of the water. I have read that this area first became known to China under the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) – but was not formally recognised by the Imperial Court until the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). This is when diplomatic and cultural contact with the King (of what was then termed the 'Liu Qiu' [琉球] Islands) was established - known today by the Japanese transliteration of 'Ryukyu'. 琉 (liu2) = sparkling-stone, jade, mining-stone (from previously uncultivated land), precious-stone, arriving, and breaking through (to a place far away - and situated on the fringes of the known world) 球 (qui2) = beautiful-jade, polished-jade, refined-jade, jade percussion instrument, earth, ball, and pearl. The Chinese Mariners must have been taken with the beauty of the Ryukyu Islands - as the term '玉' (yu4) – or ‘jade’ - appears as the dominant left-hand particle of both ideograms forming the name ‘Liu Qiu’. From the Tang Dynasty onwards, the Liu Qiu Islands were considered a distant (but important) part of the Tributary System of Imperial China. In return for a continuous show of annual respect (usually in the form of expensive gifts and/or elements of trade, etc) China shared her extensive culture. It was not until 1872 CE, however, that Imperial Japan took decisive action to annex all of the ‘Ryukyu’ Islands – and it was around this time that the term ‘Okinawa’ was developed to describe the Southern two-thirds of the Ryukyu Island Chain – now a ‘Prefecture’ of Japan. This history explains why the ideograms for ‘Okinawa’ are written in (Japanese) ‘Kanji’ - and are not obviously ‘Chinese’ in structure (as is the far older name of ‘Liu Qiu’). Is it possible to ‘reverse-engineer’ the Kanji ideograms associated with the name ‘Okinawa’ (沖縄) and work backwards as it were – to the original Chinese ideograms? The answer is ‘yes’ – as such an exercise might well shed some more light on the meaning of the name itself. Japanese - 縄 (nawa) = Chinese – ‘繩’ (sheng2) When adjusted in this manner - the Japanese name of ‘Okinawa’ (沖縄) is rendered into the Chinese language as ‘Chongsheng’ (沖繩). Whereas the first ‘Kanji’ ideogram of ‘沖’ (oki) remains identical with its Chinese counterpart of ‘沖’ (chong) - the second ‘Kanji’ ideogram (縄 - nawa) undergoes a substantial modification (繩 - sheng). From this improved data a more precise definition of the name ‘Okinawa’ can be ascertained through the assessment of the Chinese ideograms that serve as the foundation of the Kanji ideograms – working from the assumption that this meaning is still culturally implied through the use of ‘Kanji’ in Japan – even if such a meaning is not readily observable within the structure of the ‘Kanji’ ideograms themselves. 沖 (chong1) is comprised of a left and a right particle: Left-Particle = ‘氵’ which is a contraction of ‘水’ (shui3) – meaning water, river, flood, expanse of water, and liquid, etc. Right-Particle = ‘中’ (zhong1) refers to the concept of something being ‘central’, in the ‘middle’, or being perfectly ‘balanced’. It can also refer to an ‘arrow’ hitting the ‘centre’ with a perfect ease. Therefore, the use of 沖 (chong1) in this context - probably refers to an object that centrally exists within a body of water. 繩 (sheng2) is comprised of a left and right particle. Left-Particle = ‘糹’ which is a contraction of ‘糸’ (mi4) – meaning something that resembles a ‘silken thread’, a ‘thin’ and ‘flexible’ cord, a ‘rope’ or ‘string’, etc. This may also refer to the act of ‘weaving’ or to an object (like a rope, string, or strand) which is ‘woven’ into existence – perhaps implying a ‘cohesion’ attained through an ‘inter-locking’ agency, etc. Right-Particle = ‘黽’ (meng3) – this was originally written as a depiction of a type of frog – but evolved to be used generally to describe the act of ‘striving’, ‘endeavouring’, or ‘working hard’ (nin3). However, I am of the opinion that more practical attributes are at work in this instance. An old (but simplified) version of this ideogram is ‘黾’ – which demonstrates a clarification of what used to be a ‘frog’: This explains why there is said to be an ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ element to this particle: Upper-Element = ‘口’ (kou3) – signifies an ‘open mouth’, ‘entrance’, ‘mouth of a river’, and ‘port’. This can also denote a ‘boundary’ and a ‘hole’ or ‘indent’. This used to represent the head of a frog. Lower-Element = ‘电’ (dian4) – denotes ‘forked-lightning’, ‘energy’ and ‘electricity’, etc. Although evolving from the body of a frog – this element conveys not only the overt power of lightning – but perhaps retains something of the ‘shape’ of forked lightning in its usage as a noun. Perhaps 繩 (sheng2) is a descriptive term used to describe a port that allows entry to a string of islands which seem to take the shape of a rope that geographically unfurls - like forked lightning traversing the sky. Conclusion The term ‘Chongsheng’ (沖繩) – or ‘Okinawa’ - probably refers to a string of islands (and ports) which exist within a broad expanse of open sea - like a rope floating upon the surface of the water (the shape of which resembles that of forked-lightning). This place may be difficult to reach – and the people encountered may be very hard working. It is highly likely that these islands seem to float like a frog on the surface of the water – hence the selection of these ideograms. Of course, the post-1872 Japanese Authorities chose to use the Kanji ideograms of ‘沖縄’ to convey the concept and meaning of the name ‘Oki-Nawa’. In Chinese language texts, I do not see Okinawa referred to as an isolated unit of geographical description. This is because Chinese literature refers to the entire Chain of Islands by the far older and more traditional name of 'Liu Qiu' (琉球) – which was politically acknowledged through ancient diplomatic exchange. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the post-1872 Japanese Authorities did not abolish this Chinese name – but borrowed it – simply transliterating it into the now well-known ‘Ryukyu’ Islands. Okinawa is only around two-thirds of the Southern-Central area of the Ryukyu Islands – but as far as the ancient Chinese were concerned, the ‘King of Ryukyu’ was the ‘King’ of the entire geographical area defined by this term. Whereas the Chinese term is prosaic (poetically speaking of ‘jade’ and ‘unexplored’ land – the Japanese term might well be practical as it seems to be describing the ‘rope’ that is extensively used in sailing ships, boats, and other floating entities – including the requirement to ‘moor’ such objects in purpose-built ports. The difference in the two-names probably reflects the developing socio-economic conditions prevalent throughout the Island Chain at the time of conception – with around 1500 years separating the development of the two names. Chinese Language Text:

0 Comments

Japanese Karate-Do (General) - 'Mawashi-Uke' (廻し受け): Mawa (廻) = rotation, turning, rounded and circular, shi (し) = four-corners, all-areas and comprensive-cover U (受) = receive, meet, accept and stoically bear (suffer) Ke (け) = stratagem, plan, calculation and measure Okinawan Goju Ryu Karate-Do - 'Toro Gushi-Uke' (虎口受け): Toro Gushi (虎口) = literally 'Tiger-Mouth' envelopes the enemy - and closes inward from all-sides at once U (受) = receive, meet, accept and stoically bear (suffer) Ke (け) = stratagem, plan, calculation and measure Southern China Gongfu Equivalent: Double Butterfly Open-Palm = 双蝶掌 (Shuang Die Zhang) Okinawan Goju-Ryu 'condenses' many of these Southern Gongfu Movements for efficiency. Long stances are shortened whilst reaching arm-movements are brought closer to the body (perhaps adapted for practitioners spending long periods on boats). Many Hakka Gongfu Styles originating in the North progressed through this adaptation process in South China. Our Family Style did not - but virtually all the Clan Styles around our village did. Tora - Tiger - can also be pronounced 'Koko'. In Fujian this can be 'Ho Kho'. Sometimes, despite the literal interpretation of 'Tiger Mouth' - it is used in Chinese and Japanese texts to mean 'Jaws of Death! The Chinese text states that Goju Ryu is a genuine transmission of 'Nan Quan' (Southern Fist). 攻防一体虎口廻受 Attack and defence are integrated - the open tiger's mouth simultaneously envelopes and traps.

Dear Tony Interesting. Thank you for your knowledgeable explanation of sparring - an adult 'tiger playing with a cub'. This inspired me to research 'Ran-Dori' in Japanese-language sources - which is written as '乱取り' - '乱捕り' and 'らん‐どり'. Both of the following Japanese-language Wiki-entries (I have checked the data is correct) should be read side by side to gain an all-round clarity - as the 'Randori' entry does not specifically mention Karate-Do - whilst the 'Kumite' page explains that in some Styles of Karate-Do - 'Kumite' is referred to as 'Randori'. Randori - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate) Kumite - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate) I suspect the inference is that in Okinawan Karate-Do the term 'Randori' is used - whilst in Mainland Japan - the term 'Kumite' is the preferred. Difficult to say, but as you know, 'nuance' and 'implication' is an important part of Japanese communication. What is NOT said is as important (sometimes more so) than what IS said. Perhaps this Yin-Yang observation is just as important for sparring - whatever its origination and purpose. As for the traditional Japanese and Chinese ideograms - this is what we have: 乱取りand 乱捕り 乱 (ran) = chaos, disorder 取 - 捕 (to) = take hold of, gather, control, arrest り(ri) = logic, reason, understanding Therefore, 'Ran-Tori' and 'Ran-Dori' are synonymous - with the concept expressed in its written form as '乱-取り' - ot 'Chaos (Random Movement) - Seize Control of'. What is 'chaotic' in the environment is wilfully taken control of - by imposing an outside order upon it. This suggests that the 'non-controlled' is 'controlled' by the structure of Kata-technique - which is brought to bear by an expert. There also seems to be the suggestion that that which 'moves' - is wilfully brought to 'stillness'. As for a Chinese-language counter-part, perhaps we have: 乱 - 亂 (luan4) = disorderly, unstable, unrest, confused and wild (Japanese = 'turbulent') 取 (qu3) = take hold, fetch, receive, obtain and select り- 理 (li4) = put into order, tidy up, manage, reason, logic and rule It would seem that the Japanese term of 'Ran-Dori' equates to the Chinese term of 'Luan-Quli' - or 'Disorder - (into) Order Rule'. Your reply inspired me to think about what the Japanese '乱' (Ran) - or Chinese equivalent '亂' (luan4) - actually means. What is the definition of the 'disorder' being referenced to when 'Ran-Dori' is being discussed? Therefore, '亂' (luan4) is comprised of a 'left' and 'right' particle: Left Particle = 𤔔 (luan4) means to 'govern' and 'control' - and is structured as follows: a) Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. b) Lower (Inner) Element = 幺 (yao1) - a contraction of '糸' (mi4) which refers to 'thin silk threads'. c) Lower (Outer) Element = 冂 (jiong1) this is a 'comb', 'beater' or 'heddle' - a device to 'order' the silken threads that require weaving. In normal usage, this ideogram denotes the structured boundary that clearly demarks the city limits. Right Particle =乚 (yi3) is a contraction of '隱' (yin3) - meaning to 'hide', 'conceal' or 'cover-up', etc, as in 'something is missing'. It can also refer to a required process that is 'profound', 'subtle' and 'delicate' - but which is currently 'lacking'. It may also mean 'secret' and 'inward' or 'inner', etc. I would say that 'obscuration' is what this ideogram refers to in its meaning. Conclusion The literal meaning of '亂' (luan4) [or 'Ran' in 'Ran-dori] - is that it refers to a lack of skilful organising ability (disorder and confusion). The thin silk threads are not placed correctly on the wooden frame (loom) - and therefore cannot be 'weaved' together in an orderly fashion. This entire process lacks the required profound knowledge and experience to achieve the objective - thus the hands (and body) cannot be used in the appropriate manner. Ran-Dori (乱捕り), as a complete process, suggests that it is the opposite of the above 'lack of skill' that is require in sparring. Not only is this skill required, but 'ri' (li) element (理 - li3) - suggests a 'regulation' and an 'administration' (premised upon logic and reason) - such as the profound skill required to 'cut' and 'polish' jade. I was discussing Randori with another language expert and they gave me more data which I have added to this paragraph: 'Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. ' I was curious as to why the two hands were so specific in their orientation and my colleague said that they are clearly carrying out the process required for ancient 'weaving'. One hand is laying the 'warp' - or 'vertical' thread down through the loom - whilst the other right hand is performing the function of 'weaving' multiple 'weft' threads into place horizontally across the loom! As a matter of comparison - the 'Kumi' (組) in Kumi-te (組手) - Chinese 'Zu Shou' - means to 'weave continuously'. This translates as 'to be skilful' (the silken threads are skilfully woven [糹-si1] together forever - like the longevity of a sacrificial vessel [且 - qie3] - which are traditionally made out of stone). Therefore, Kumi-te literally refers to a 'continuous skill that unfolds through the hand'. This may be compared to the term 'Ran-Dori' which refers to a 'missing skill' that has yet to be 'acquired' and is in the midst of 'being acquired' (through developmental training) - whilst Kumi-te implies that the required skill is already present and should manifest automatically.

The term 'Jin' (劲) is used here to denote a 'penetrating' and 'cutting' power. There is also the connotation of 'vigour' and to 'express'. Left-hand Particle = 巠 (jing1) - or 'streams running underground' (a 'hidden' or 'inner' power) - and 'to flow' (without interruption). A complex particle comprised of: 一 = yi1 - number one, unified, complete 巛 = chuan1 - river, stream, tide, flow 工 = gong1 - effort, labour, work, technique Right-hand Particle = 力 (yi4) - or 'strength, power, force' comprised of: 𠃌 = gun3 - a hook bent inward (able to effortlessly suspend weight) 丿= yi4 - clearing all obstructions away to achieve a clear objective

Tony to Adrian: Good evening Adrian. Quite a interesting style off Okinawan karate. From my position , very Chinese influence. What do you think. Tony Adrian to Tony: The Japanese language title reads: Secret Tradition! (秘伝) Matayoshi Shinpou (又吉真豊) Direct Transmission - Handed-Down (直伝) White Crane (白鶴) Military Law (兵法) 3rd Dan (三段) [Apllicable] Form (の形) Superb. The pelvic-girdle is empowered with ki to deflect incoming power - such as a round-kick. The back-leg rootedness of the White Crane generates the rising power exhibited flowing through the correctly empowered front-leg (the discussion near the beginning), and then up through the arms, wrists, palms fingers, thumbs and finger tips - in gripping, deflecting, gouging, punching, tearing and penetrating. Incidentally, the Chinese characters are either retained or slightly modified in this Okinawan script. With '兵法' (Military Law) this is 'Bing Fa' in the Chinese language ('Hei-ho' within Japanese) - and is often better known in the West as the 'Art of War' - an early text penned by Sunzi. Perhaps in this context a better translation is 'Soldier's Law'.

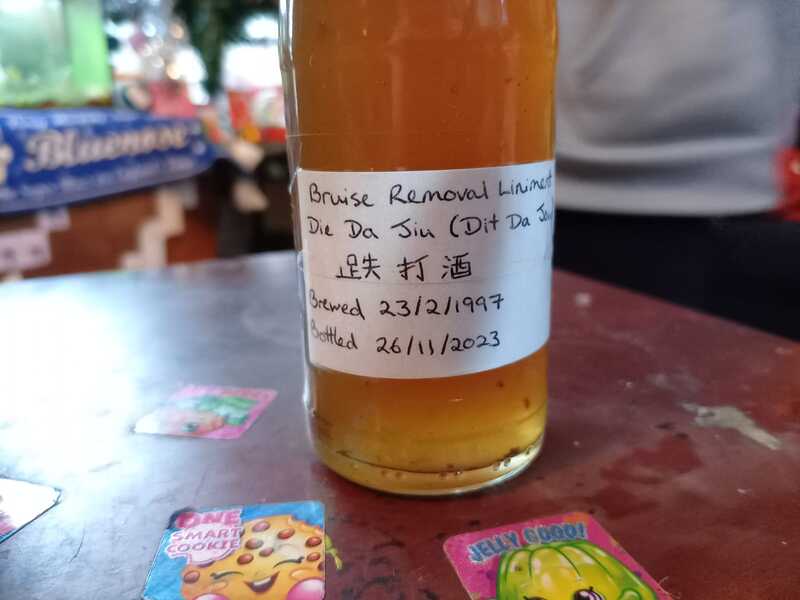

All genuine Chinese gongfu (family) lineages possess a TCM (folk) prescription for 'Iron Fighting Wine'! These pages written in Medical Chinese ideograms are highly valued and treasured - even though they possess a number of different (but related) names - all variants of theme! As we value Traditional Okinawan Goju Ryu - this bottle is heading to a very good and esteemed Instructor of that martial art living in the UK! Brewing and bottling Dit Da Jow is a family affair that involves an element of profound spirituality.

The above is a video on Bili Bili designed for Goju Ryu practitioners in China (or Chinese language speakers around the world). Essentially, Chinese language subtitles have been affixed - with Okinawan-Japanese concepts (cultural interpretations) translated into Chinese philosophical terms. This was uploaded on September 7th, 2022 - but I have not encountered it before. The direction of breathing is explained (stating there are two methods) - with 'kime' (決め) emphasised. This is written as '决定' (Jue Ding) in the Chinese language. 决 (決) = jue2 (ki) - certainty, dredge and kill 定 (め) = ding4 (me) - steady, fix and stabilise Interestingly, within Buddhist philosophy the Chinese ideogram '覺' is also catalogued (within modern Pinyin) as 'jue2' - and is related in structure to '决' (jue2) which is used above in 'kime'. This means the ideograms share a common root and depicts a related meaning. Whereas '决' (jue2) suggests a mind-enforced control over the body - '覺' (jue2) refers to the achievement of 'enlightenment' through the mind 'waking-up' - a state achieved only through following the utmost disciplined paths of bodily control. Perhaps the two variants of these ideograms are related. I would suggest this is the case on the grounds that '定' (ding4) - the second ideogram used within 'kime' - is also used to translate the Sanskrit term 'Samadhi' - which refers to a method of 'fixing' the awareness of the mind in one place (preventing the surface mind from moving about without control) - and thereby achieving a permanent 'stillness' of mind (which allows for the perception of 'emptiness'). Again, the physical body is subject to the utmost discipline (through the Precepts as taught in the Vinaya Discipline). The breathing is 'Daoist' in nature and involves a basic filling-up of the dantian with qi (inward breath into the lowest area of the pelvic girdle) - which is then redistributed throughout all the regions of the body (through the outward breath). The retained tension 'pulls' the qi into the dantian - and the maintained muscle tension 'extracts' the accumulated qi into the extremities (both breaths meditated by the awareness of the mind). The 'advanced' breathing is only hinted at and involves the microcosmic circulation of the qi. Qi is breathed into the dantian - which triggers the flow of qi up the Governing Vessel (which runs through the spinal column) and over the top of the head to the upper palate of the mouth. The tongue touches the upper palate with completes the circuit between the Governing Vessel and the Conception Vessel - which starts in the tongue, flows down the front of the body and through the grown and around to the perineum - where the Governing Vessel begins. The Sanchin breathing strengthens and maintains this Daoist breathing.

As regards 'tradition', 'lineage' and 'respect' - these are aboth fundamental Chinese cultural aspects which were brought suddenly into the modern world in 1911 (the ‘Nationalist’ Revolution) and 1949 (the ‘Socialist’ Revolution). In Japan, this process began with the Meiji Restoration of 1868. This all evolves around the concept of 'face' (面子 - Mian Zi) - or the ability to walk through the public spaces with one's dignity fully intact and face on display. To traverse the public spaces used to demand a stern adherence to the teachings of 'Confucius' as defined by various philosophers and politicians, etc. Indeed, Confucianism regulated not only the society of China for over two-thousand years, but also many other countries including Korea, Japan, Vietnam and Okinawa (including large areas of South-East Asia). Furthermore, wherever Chinese people have migrated - Confucianism has followed. Confucianism still defines Chinese society, but the way this happens has evolved over the centuries and can still seem baffling to the uninitiated. Regardless of this, understanding ‘Confucianism’ is the only way ‘in’ and ‘out’ of a Chinese cultural grouping. In the old days, breaking these rules led to the breaking of one's body - a simple correlation between spiritual morality and physical punishment. The individual body used to be the property of one's parents and belonged to the State (that is to the 'Emperor'). The body of a child used to represent the continuation of a family's ancestral 'Qi' energy and the lasting of the Clan Surname. Judicial execution often involved public beheading (the 'loss' of face through the loss of the head) – a punitive process which usually including the killing of all members of the same family (depending upon the severity of the offense). Social execution involved the 'exclusion' of an individual and a family (Clan) - from all meaningful social interaction. It is interesting to note that despite the differences in political and economic view that exist between Beijing and Taipei, for instance, Chinese people living in Taiwan and Mainland China would agree (both implicitly and explicitly) about what 'face' is, and about what 'losing' and 'saving' face actually entails - so important is this central aspect of Chinese culture. Today, the forces of modernity have radically redefined this tradition - but occasionally murders and beatings do still occur throughout Chinese society - usually involving disputes regarding love affairs, relationship betrayals and intimate deviations, etc. Of course, if an individual is known to have behaved in a terrible fashion for whatever reason, social ostracization tends to follow. Remember, China is comprised of 56 ethnicities which enlarged through the Chinese diaspora as it intermixes with different people throughout the world. This means that 'saving face' and 'losing face' tends to vary in interpretation. For instance, my modern academic colleagues in China tend not to give 'face' much consideration - but the older members of our Chinese family still live their lives by this concept! Okinawa, for instance, is still being punished by the Mainland Japanese for being historically ‘Chinese’ – and this has involved the post-1945 US Military Bases being lodged of the Island. This US neo-imperialist presence has been compounded by an assault on Ryukyu culture that has been intended to eradicate all obvious ‘Chinese’ cultural tendencies and replace these with a blend of Americana and Nipponisation. Yet the robustness of the Okinawan way of life stands inherently strong – with an older version of ‘Confucian’ ideology lurking firmly in the background and regulating the martial arts, leisure and business communities. Indeed, the Chinese concept of 'face' (面子 - Mian Zi) literally translates as 'Face Child' or 'Face Master'. The second ideogram '子' (zi3) means 'a child that is born already old and wise' - and is associated with 'Laozi' (老子) - one of the founders of Daoism. Perhaps 'Saving Face' would be better redefined as 'Preserving Face'. In England we talk of proudly holding our heads-up high in public.. Of course, in the strict Confucian model, the onus is on the individual rather than the social collective. Today, the social collective is just as responsible as the individual - so that the entirety of society works together to preserve the status quo. Now, it is as if the collective society has its own 'face' that has to be preserved in the 'face' of individual behaviour. It is a two-way street. Individual responsibility is now balanced with collective responsibility - creating a preserving 'tension' of positive interaction. An individual's 'face' is considered secondary and is only saved when the 'face' of orderly society is acknowledged and preserved. Having explained all this, there still exist pockets of Chinese culture spread throughout the world that uphold older versions of ‘Confucian’ ideology and expect all incomers to understand and respect this reality.

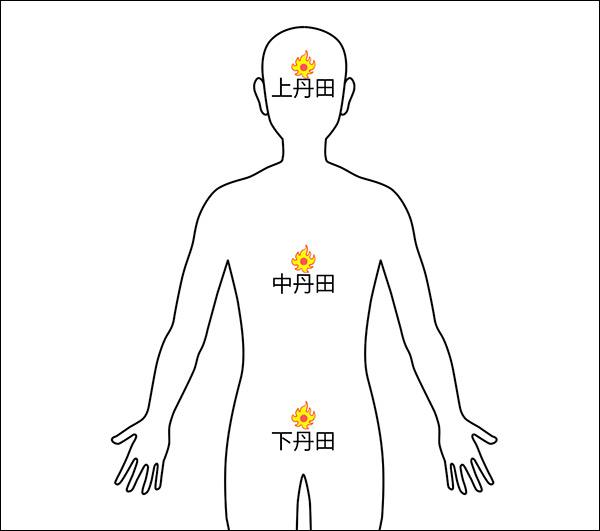

Building upon my previous work, I am considering the theory that the various Karate-Do Styles originally possessed 'different' and ‘diverse’ terms for their techniques - as each evolved from its foundational gongfu Style. For instance, traditional Chinese gongfu does not possess the unity or conformity that defines modern (Okinawan) Karate-Do - an attribute which gives Karate-Do an inherent robustness and strength – achieved through the process of removing of diversity. On the other hand, even within Chinese gongfu Forms contained within the same Style - exactly the same movement often possesses a completely different name! This is often due to a) metaphysical interpretations (linked to TCM) and b) to material practicality. A lower block may be performed with an open hand or closed fist - use the edge, palm or back of the open hand - or the 'Hammer Fist' of closed hand. The contact surface might be the boney areas of the wrist, or the bones of the fore-arm - similar to the 'Iron Arm' training performed in deep Horse Stance with fore-arms and wrists robustly striking one another (this is a Hakka speciality, and we do this from childhood - generating tremendous power when an adult)! I remember performing this type of conditioning within the Goju Ryu Karate-Do Style - only in a higher (Sanchin) Stance. Experts tend to adjust their technique to become like 'water' - which envelops and controls any 'stone-like' techniques! The metaphysical reasons are far too in-depth to cover in a single article – but what follows is a basic summary. The 'jing' [精] (retained sexual energy) and 'qi' [氣] (breath, food, drink and moral thought) are circulated up the 'Governing Vessel' (督脈 - Du Mai) and down the 'Conception Vessel' (任脉 - Ren Mai) in a continuous microcosmic cycle (小周天 - Xiao Zhou Tian). What the Japanese people renamed the 'Hara' (はら) - or '払 (fan3) in the Chinese language (this ideogram has no immediate metaphysical meaning within the modern Chinese language) - is I believe a reworking of the well-known lower ‘丹田’ (Dan Tian) situated 1.5-3 inches below the navel. The three 'Dan Tian' locations (分 - Fen) are found in TCM as follows: 1) Upper Dan Tian (上丹田 - Shang Dan Tian) - situated in the centre of the forehead (the so-called 'Third-Eye' or 'Yin Tang' [印堂] point [穴 - Xue]) situated on the ‘Governing Vessel’. This is where '神' (Shen) - or 'empty' and 'all-embracing' consciousness is first formed prior to 'expanding' through the body (uniting the three 'Dan Tian') and penetrating the physical environment. 2) Middle Dan Tian (中丹田 - Zhong Dan Tian) - situated around the Solar Plexus (the 'Tan Zhong' [膻中] point) on the ‘Conception Vessel’. 3) Lower Dan Tian (下丹田 - Xia Dan Tian) - situated 15 - 3 inches below the navel - depending upon medical source (the 'Guan Yuan' [关元] point) on the ‘Conception Vessel’. These three pressure-points all exist upon a unified line of inner energy flow that demarks the ‘Governing Vessel’ and the 'Conception Vessel' situated on the front of body – extending deep into the tissue of the body reaching to the back of the spinal bone. This three-dimensional TCM can be observed at work with the 'Upper Dan Tian' (Governing Vessel) - which is comprised of a three-way link between the exact inner-centre of the brain-mass (泥丸宫 - Ni Wan Gong) and the exact centre-point situated at the top of the skull-bone - the so-called 'Bai Hui (百会) point. All genuine (traditional) Chinese gongfu is comprised of TCM thinking, methodology and spirituality. Killing, maiming (hurting the opponent's mind and body - either temporarily or permanently) or stopping the opponent without hurting their mind or body - are the physical objectives. As for the spiritual side (which I think is also embedded in the 'Gedan Bara-I' - 'Gedan Hara-I') - this is a complex issue. Gee reminded me that one form of the lower block we practice in our Hakka Family Style is performed on each side of the body - and does not cross the front of the torso at all (and therefore does not traverse the Lower Dan Tian point – or ‘Hara’ in the Japanese language). The 'Governing Vessel' and ‘Conception Vessel’ ‘connect’ between the roof of the mouth (just behind the front upper-teeth) and is connected to the 'Conception Vessel' via the top of the tongue. Whereas the Upper Dan Tian appears within, upon and around the ‘Governing Vessel’ - the Middle and Lower Dan Tian appear within, upon and around the 'Conception Vessel'. However, the following analysis is a correct correlation of Karate-Do ‘Blocks’ and ‘Dan Tian’ pressure-points: Jo-Dan (Upper Level) Uke (Block) = Upper Dan Tian Chu-Dan (Middle Level) Uke (Block) = Middle Dan Tian Ge-Dan (Lower Level) Hara-I (Block) = Lower Dan Tian This suggests that the Upper Block (when performed to the immediate front of the body) travels through the Upper Dan Tian. The Middle Block (when performed to the immediate front of the body) travels through the Middle Dan Tian, and the Lower Block (when performed to the immediate front of the body) travels through the Lower Dan Tian. I have accessed a Japanese language page regarding the 'Dan Tian' and this confirms the link between the Lower Dan Tian and the 'Hara'. The Chinese name for the Lower Dan Tian is '关元' (Guan Yuan) which is rendered into the Japanese language as '関元' (Seki Gen). This is also referred to as 'はら' (Hara) supposedly due to the influence of Zen Buddhist practice - but as a Chinese Ch'an Buddhist myself, I have no idea why this should historically be the case. However, by building upon my earlier work regarding ‘Ge-Dan Bara-I’ (下段払い)’ - if we follow this line of reasoning, the original (or 'early') Karate-Do Blocks could have been called something like this: Jo-Dan Gindo-I (上段 銀堂 い) = Upper Level 'Gindo' (Upper Dan Tian) Forceful Execute! Chu-Dan Nichu-I (中段 丹中 い) = Middle Level 'Nichu' (Middle Dan Tian) Forceful Execute! Ge-Dan Bara-I’ (下段払い) which should read ‘Ge-Dan Hara-I’ = Lower Block 'Hara' (Lower Dan Tian) Forceful Execute! To arrive at the above speculation - I have 'reversed engineered' the structure of the Lower Block (conventionally and incorrectly rendered into English as ‘Ge-Dan Bara-I’ - [下段払い] - when it should read ‘Ge-Dan Hara-I') into the Middle and Upper versions. I have used Japanese language transliterations of the original TCM designations regarding the Dan Tian points even though I do not know the 'slang' terms for these Japanese words. I say this as I am told that 'Hara' is a slang term for the Chinese TCM language term '关元' (Guan Yuan) [which refers to the Lower Dan Tian point] - which translates as to 'Seal the Source' or 'Stop the Leakage to Strengthen the Foundation'. Traditionally, the Japanese people developed the ritual of 'cutting-open' (Hara-Kiri) this anatomical area as a means of 'releasing' what they thought to be their 'life spirit'. I know of no Chinese cultural equivalent to this practice. The 'Blocking' techniques of Karate-Do, however, serve the exact 'opposite' of this destructive practice – and this is achieved by the Karate-Do Blocks 'protecting' these three energy centres - which are considered vital for the evolution of life!

Thanks Tony!

What you say about Miyagi Chojun's attitude toward 'Bunkai' is typical of traditional Chinese gongfu. Many Masters will know one or two 'favourite' applications of the various Form moves - but will always teach that each Form movement has hundreds (or more) applications that should not (and cannot) be limited to a single interpretation. This being the case, where does the concept of 'Bunkai' come from within Karate-Do? Certainly, there are old photographs of Goju Ryu 'Disciples' in Okinawa applying Kata movements as self-defence - quite often as Miyagi Chojun is looking on. As far as Southern Chinese gongfu concepts are concerned - I am not familiar with the term '分解' (Fen Jie) - which in Cantonese is pronounced 'Fan Gaai' and in Hakka 'Fun Ge'. However, there are some dialects of Hakka (not that spoken in my family - but in villages further North) - which pronounce '分解' as 'Bun Kiai'. Within the Fujian dialect - '分解' is pronounced 'Hun Kai' or 'Pun Ke', etc. This seems to morph quite naturally into the Okinawan-Japanese 'Bun Kai' - and would suggest the concept spread (linguistically) from South China to Okinawa. Of course, this might not be the case and could suggest the experience was developed in Okinawa (as part of the transmission process) and 'reflected' in the adoption of appropriate sounding 'Chinese' terms. I would agree fully with Miyagi Chojun - as I teach our family gongfu in just that way. Yes - if asked I can easily explain the purpose behind this or that movement - but it is only through 'practicing' each movement until the human awareness and perception penetrates its fully and its multitudinous (and 'empty') essence is found - that the 'movement' itself is totally comprehended. I was always taught that the ability to sit for long periods of time in cross-legged meditation is the highest expression of all gongfu Forms. On the other hand, a 'Master Chan' in Malaysia (a 'relative') focused all his life on perfecting just one Form movement - which involves the grabbing hold of a single (attacking) front-kicking leg - and 'breaking' that leg around the 'knee-joint'. He would apply a downward fore-arm (elbow) strike (whilst shifting into a back stance) across bamboo sticks thrust at him by students until one, two or three sticks could be easily broken! Whilst sparring, he would attempt to 'goad' an opponent into 'kicking' whilst skilfully avoiding all over incoming blows. Needless to say, the jungles of Malaysia had a number of permanently 'limping' former opponents! Thanks |

AuthorShifu Adrian Chan-Wyles (b. 1967) - Lineage (Generational) Inheritor of the Ch'an Dao Hakka Gongfu System. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed