|

0 Comments

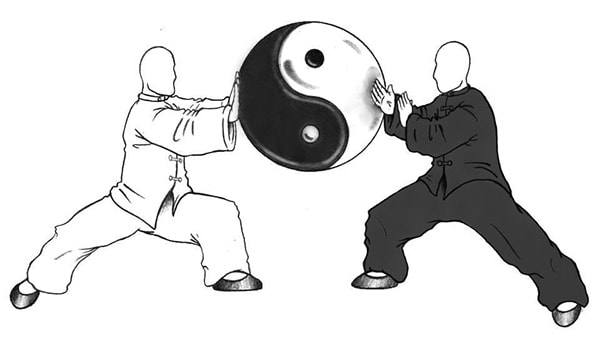

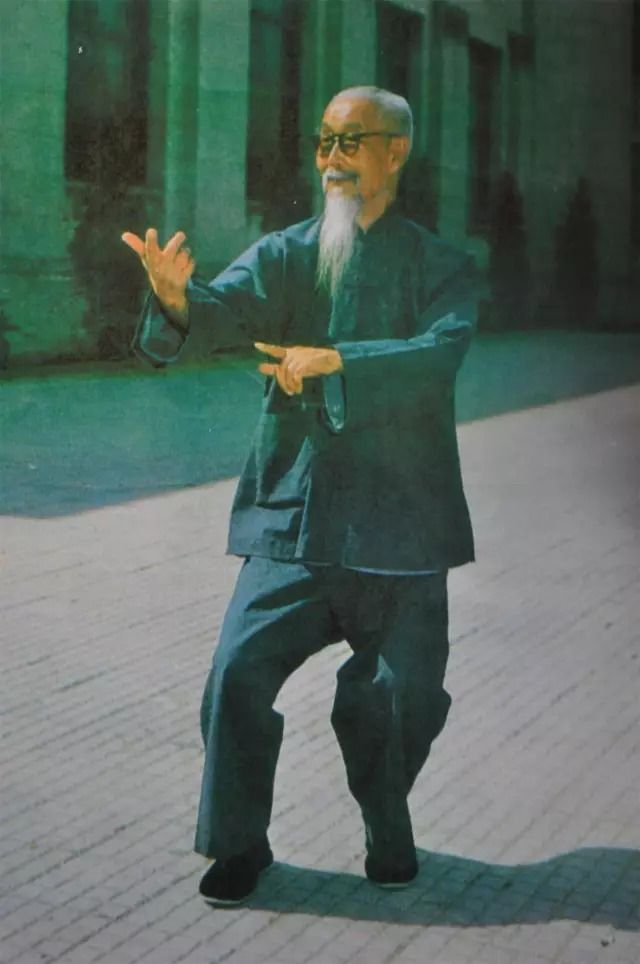

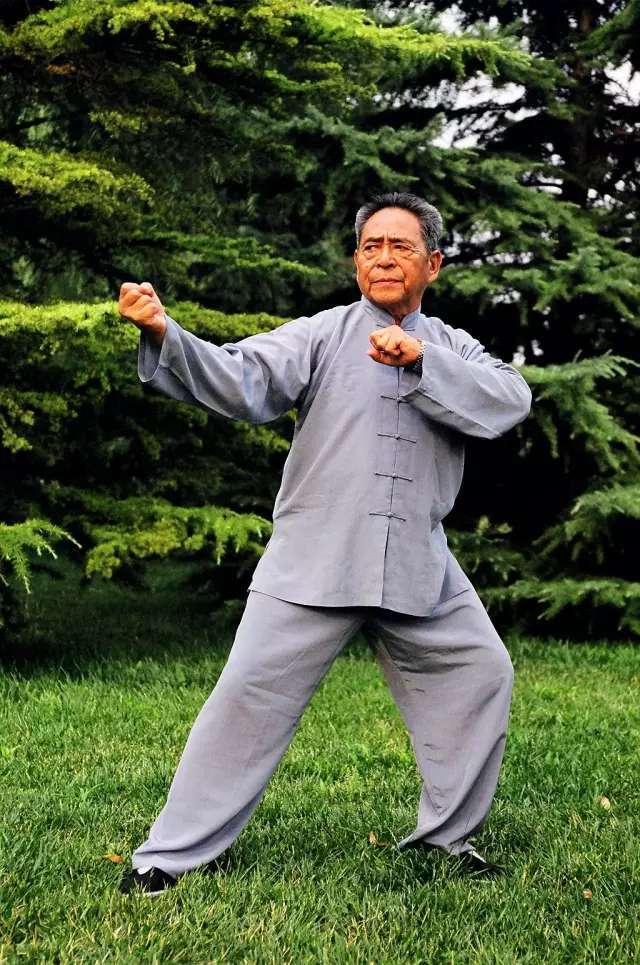

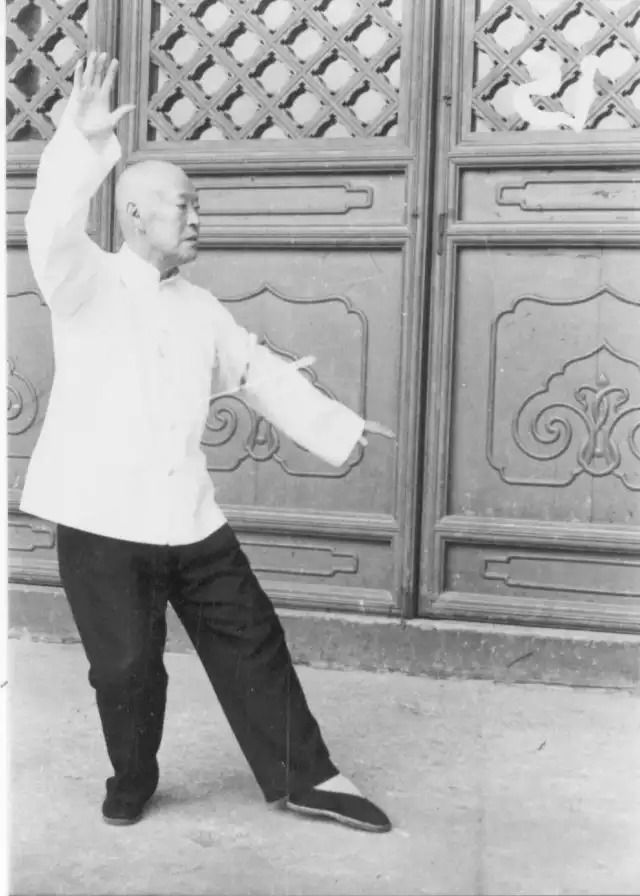

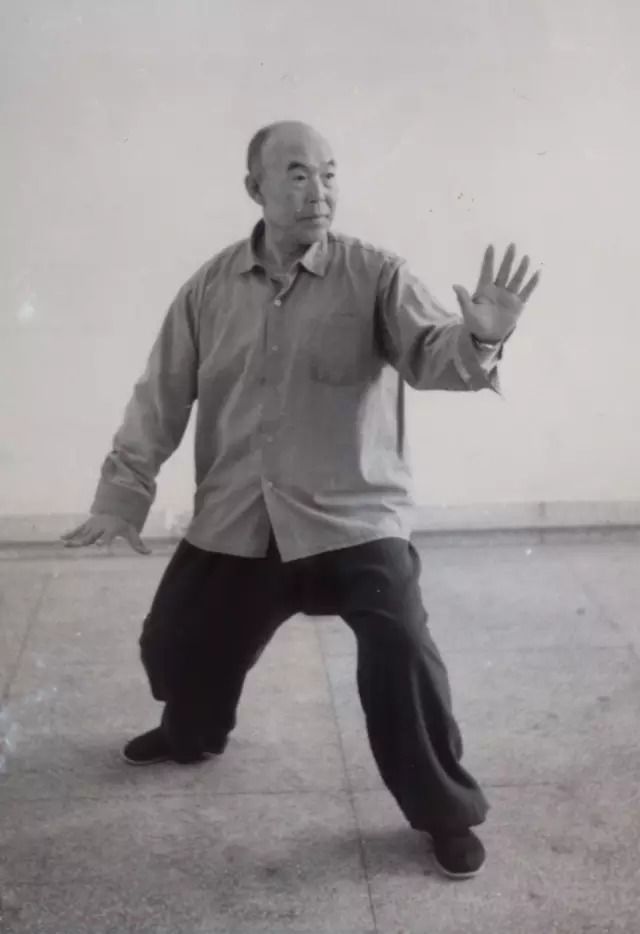

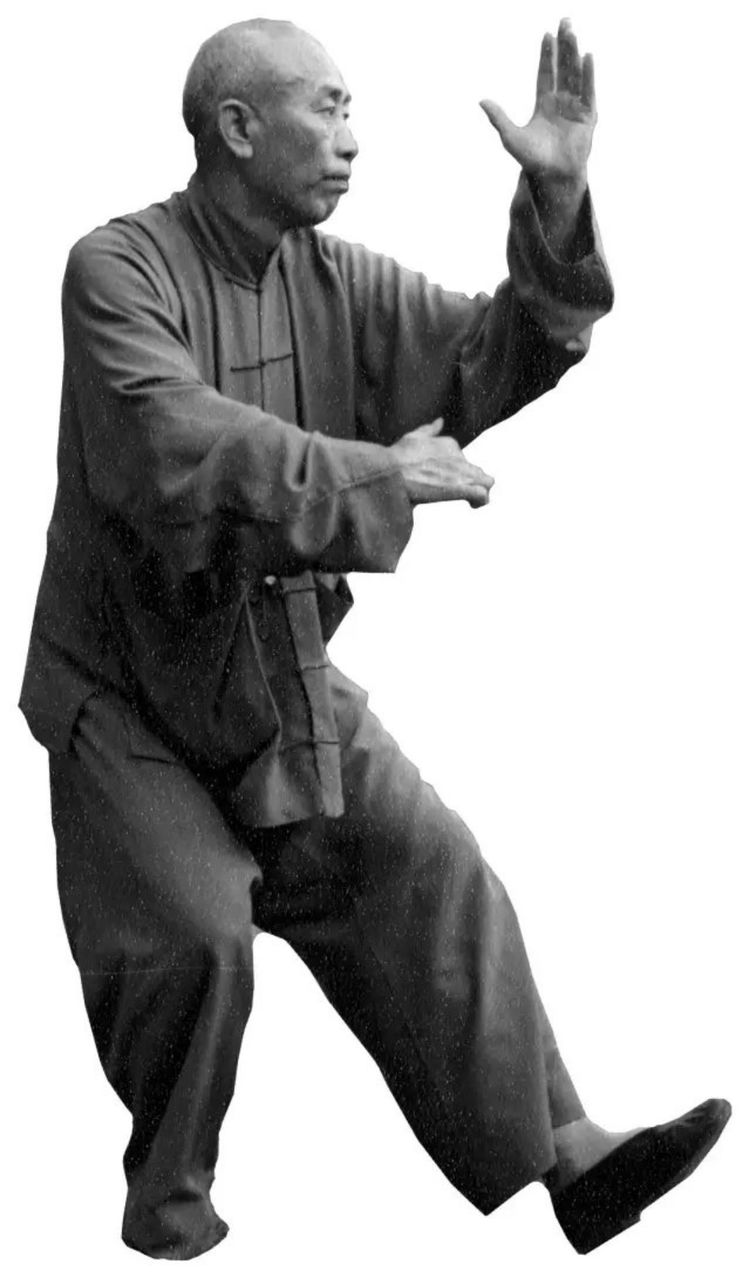

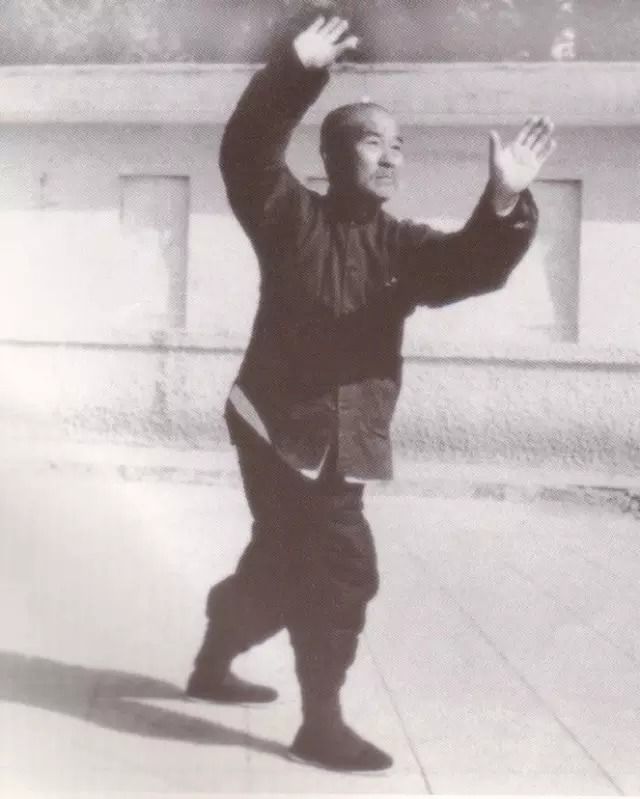

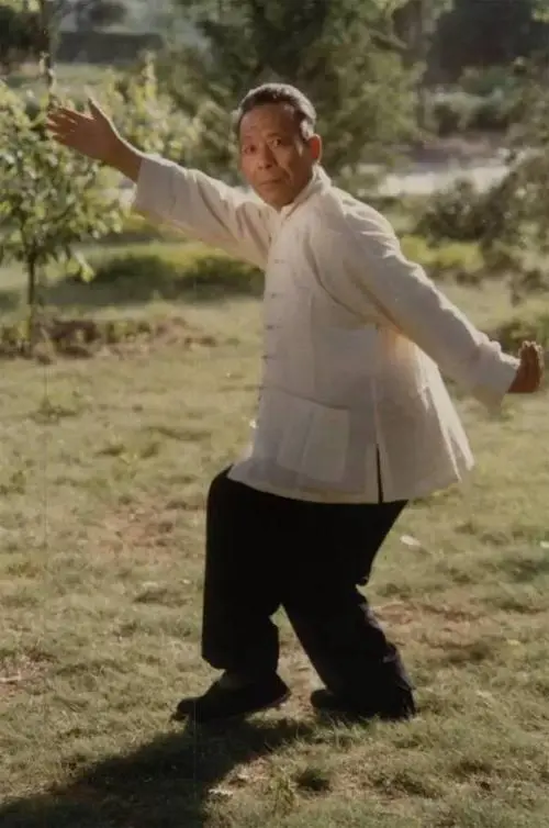

Two aspects define this exercise. First, develop the technique of using the body like a ‘bow’, and second, in so doing ‘generate’ huge amounts of energy! To achieve this ability, the physical body must cultivate three-roots, a) the ‘lower’ or ‘foot’ root (脚根 - Jiao Gen), b) the ‘middle’ or ‘waist’ root (腰根 - Yao Gen) and c) the ‘top’ or ‘head’ root (顶根 - Ding Gen). The ‘middle’ or ‘waist’ root is inherently linked to the ‘dantian’ (丹田) - or ‘centre of energy self-cultivation field’ situated two-inches below the navel and also referred to as the ‘Life Gate’ (命门 - Ming Gen). The ‘head’ (top) and ‘foot’ (lower) roots should be visualised as being ‘set’ firmly in place. The ‘waist’ (middle) root – which inherently and continuously connects the ‘top’ root to the ‘lower’ root - is then completely ‘free’ to move in a forward and back direction which does not break the all-round ‘rootedness’ and does not disrupt the harmony of the all-round alignment of the three-roots. As the ‘top’ root is linked to rarefied consciousness and divine creativity, this sense of ‘righteousness’ should permeate the other two ‘roots’ and saturates the entire mind and body of the individual practitioner. This ‘divine’ consciousness flows from the ‘head’, through the body (‘middle’ root) and down into the ground (through the ‘foot’ or ‘lower’ root). This downward flow is inherently linked with the forces of gravity which is an amalgamation of Jing (精), qi (氣) and shen (神). This combined force hits the ground and ‘rebounds’ upwards re-tracing its direction of travel. Although this energy circulates around and through the 12-14 qi energy channels that run through the entire human body – this energy-process also travels through the centre of the bones (both upwards and downwards) developing the inner marrow and outer bone structure).

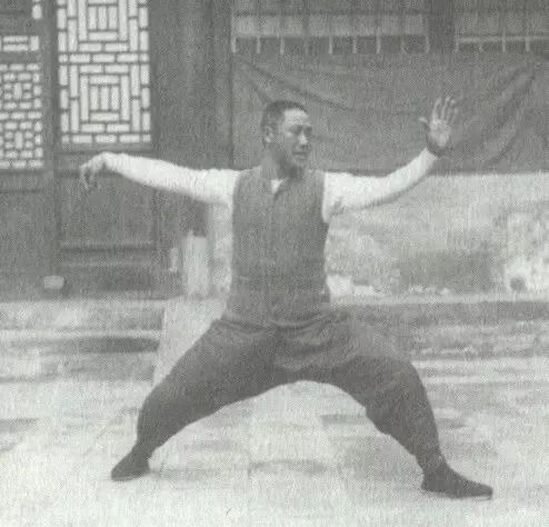

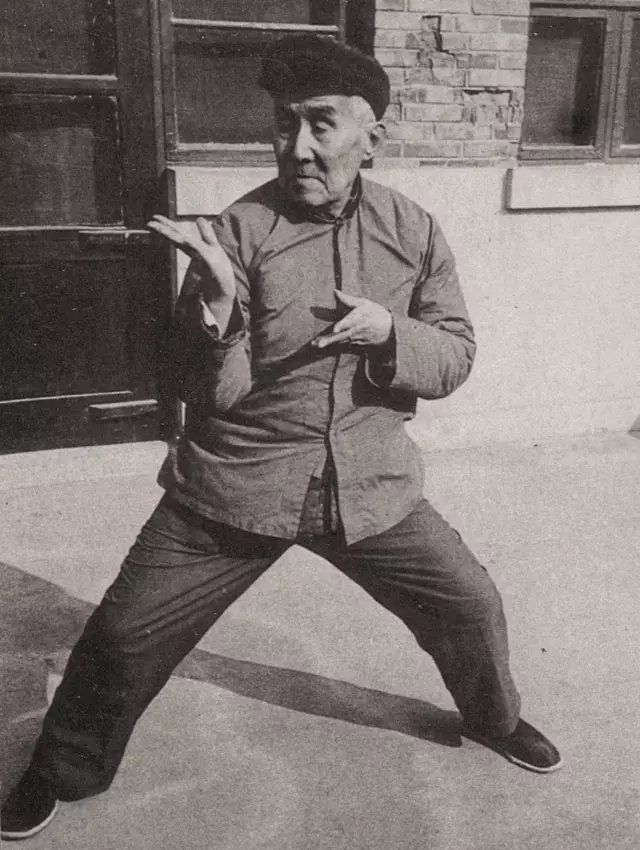

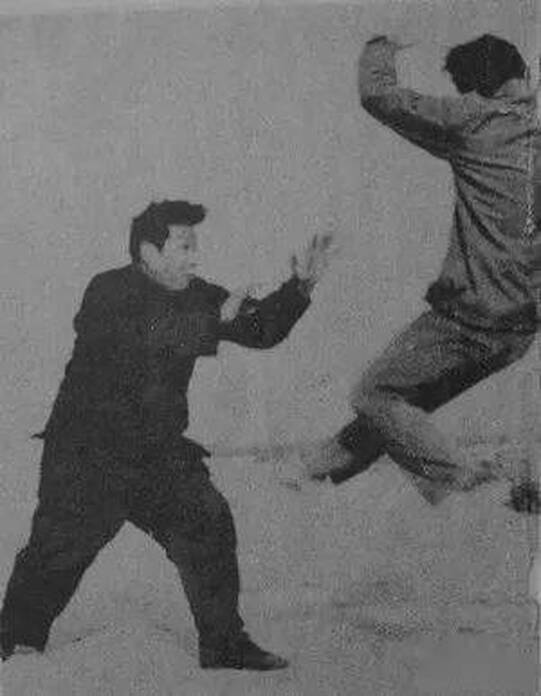

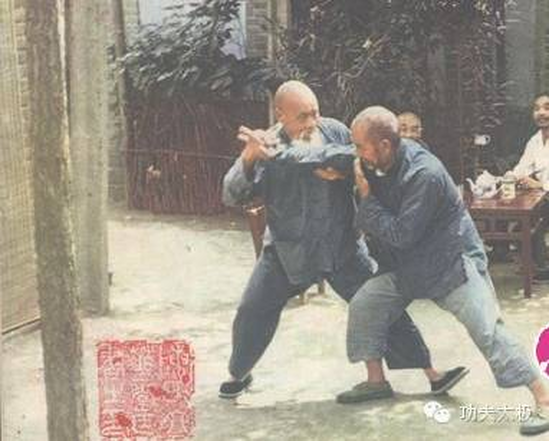

What does this mean in practical purposes? A person who is so ‘rooted’ remains immovable when an outside force is placed against any part of heir still body. The more pressure that is exerted – the stronger their immovability becomes. Although the head and feet do not move – the waist act as a shock-absorber. Such a practitioner can absorb, re-direct and divert all incoming energy through an expert ‘waist’ positioning and subtle repositioning. Indeed, such an ongoing procedure will ‘tire’ a continuously ‘pushing’ opponent. All incoming force is redistributed through the hollow centre of the bones and safely into the ground. This simultaneously disarms an aggressor and ‘strengthens’ the immovability’ of such a practitioner. The expert positioning of the skeletal frame allows the movable waist to infinitely divert incoming force away from achieving its objective of ‘uprooting’. Once the ‘integrity’ of the opponent’s strength is broken, the movable ‘waist’ can be used to ‘repulse’ the opponent and ‘uproot’ his stance. Righteousness and ‘stillness’ are identical. When movement is correct – then ‘righteousness’ and ‘movement’ are correct. The posture can rotate and turn 180 degrees and the bow can be drawn. In an instant the bow can be ‘released’ and a tremendous force emitted in a focused direction. In reality, if the ‘lower’ root can be maintained, the other two ‘roots’ can be used to remarkable effect in combat – moving and adjusting to an opponent's movements and positionings. However, just as opponents can be unpredictable, an advanced martial artist must decide which ‘root’ to keep in-place and which ‘roots’ to move! This is how victory is assured. Stay polite and move around naturally seeking-out the openings. When it is time to deploy your advanced skills then the concept of ‘Yi’ (意) or ‘intention’ comes into play. When ‘rootedness’ has been properly achieved, then everything is achieved without any undue effort. Energy can be built-up in any area of the body and ‘released’ as your ‘intention’ sees fit. In this regard, ‘intention’, ‘righteousness’ and ‘rootedness’ are all mirrored in one another with one not existing without the other two. This type of unified power can be developed and used in any circumstance and always prevails over those with less spiritual development and martial arts skills. Just as the Jing and qi energy flows through all the energy channels and generates ‘shen’ as an empty mind – martial power of this kind appears to manifest without any undue effort. The secret, of course, is that the practitioner has spent years training the mind and body to achieve this ability. The ‘intention’ is the product of ‘stilling’ and ‘expanding’ human consciousness so that it permeates out of the head area and traverses through the entire body and out into the environment in a 360-degree deployment. The developed ‘intention’ can draw jing and qi into a certain area for health purposes, healing and longevity. With the case of ‘shen’ developed from his congealment of ‘jing’ and ‘qi’ - all the advanced spiritual states are achieved. When combined with bodyweight and the principle of skeletal alignment – a deep and inherent combat power is formed as if from nothing! Bodyweight does not exist outside of qi and jing – but firmly within these facets of traditional Chinese thought. Bodyweight has always been an important facet of this ‘hidden’ power which makes more sense in a modern context. When its presence is clearly ‘perceived’ - then is falls firmly within the context of ‘shen’ - when shen is used to equate with an expanded conscious expansion! With ‘awareness’ tremendous vigour and force are generated. The mind and body can function to a greater extent of healthiness and be prepared for a successful martial encounter. Intention becomes the essence of Taijiquan (太极拳) and the foundational ability to both ‘adapt’ to circumstance and ‘generate’ tremendous force. The main question Is ‘how?’ to use ‘intention’ to generate ‘effortlessly’ power? Within Taijiquan – the ‘Grand Ridge-pole Fist’ - the essence of this practice evolves around the principle of ‘frame’ (架 - Jia). Without understanding the use of ‘frame’ - there can be no ‘effortless’ power through the use of intention. For many people the question becomes ‘how to beat others without effort’? For most, this notion seems to contradict the reality of the material world and the use of ‘obvious’ force to defeat others. With regards to advanced Taijiquan practice there are ‘two’ forces which need to be mastered. 1) is the bodyweight which exists within the body of the practitioner, whilst 2) is the bodyweight which exists within the body of the opponent. The first drops down through the centr of the bones – hits the ground (thus ‘rooting’ a practitioner) - and then ‘rebounds’ upwards creating a reservoir of immense and effortless power which can be ‘emitted’ from any part of the body as the ‘intention’ sees fit! This process of modern physics ‘mirrors’ perfectly the thinking of Chinese traditional thinking and certainly does not contradict it! This amounts to 1) using our own strength and 2) using the strength of others. Most people remain complete unaware of these two methods of generating effortless power. Instead, they over-balanced, always ‘pressing down’ and stopping the natural rebounding force that gravity ensures is always being generated. To change this habit – the capacity to sense ‘intention’ from the ground to the top of the head must be cultivated. Instead of tensing the muscle to achieve this – the muscles are completely relaxed to allow the rebounding force to move up through the structure without hindrance. Sensing this upwards movement is the exercise of ‘intention’. This is combined with the ‘awareness’ of the bodyweight ‘sinking’ this energy into the ground and the entire cycle of ‘intention’ is attained... The qi (氣) sinks into the dantian whilst the head is ‘suspended’ and ‘buoyant’ - as if floating on an invisible cushion of air or held-up by an invisible silk cord. The top and bottom are united by a single ‘awareness’ and ‘permeating’ energy. The most difficult aspect of generating ‘effortless energy’ is learning to distinguish between a deep ‘loosening’ (松 - Song) of the body-structures and a superficial ‘relaxation’ (弛 - Chi) of those same surface-structures. Although it is true that ‘relaxation’ is the first step of training whereby the muscles, ligaments and tendons are freed of habitual ‘tension’ - this is only the beginning as the ‘intention’ or ‘awareness’ permeates these structures and generates an entirely ‘new’ organisational structure that appears sub-cellular in origination. As the bodily-structures re-orientate (like the branches of a pine-tree ‘fanning-out’) energy travels through the area in a totally different way. This is why superficial ‘relaxation’ gives-way to a profound ‘loosening’. The bottom is ‘rooted’ and connected to the ‘head’ by the ‘middle’ or ‘waist’ area with no breaks in energy transmission. Superficial relaxation must transform into a state of profound ‘loosening’ or the body-structures will never be fully transformed. Indeed, the term ‘middle embracing’ (中正 - Zhong Zheng) refers to how the ‘middle’ communicates and relates to its surroundings. This can refer to its inner or outer surroundings and is not limited to any one dimension. It is both a psychological and physical reality. Another way of looking at this is the relationship between the ‘centre’ and the ‘periphery’. This can be summed-up as simultaneously embracing the states of ‘moving’ and ‘non-moving’. Whenever the centre moves it is always balanced and in harmony with the ‘still’ periphery – when the periphery moves it is always in harmony with the ‘still’ centre. The centre must be made profoundly ‘still’ in body and mind so that the nature and quality of its communication with what is forward, back. up, down, left and right is profound and all-embracing. Unnecessary movement is divisive, whereas ‘stillness’ generates harmony as the perfect balance between yin-yang (阴阳) relationship. When ‘stillness’ and ‘movement’ must interact, then it must be as a dynamic and symmetrical balancing of well-timed opening and closing – of allowing bodyweight ‘in’ and allowing ‘bodyweight ‘out’ - of allowing the opponent’s presence ‘in’ or keeping the opponent's presence ‘out’. Traditionally, this is explained through the mastery of the concepts of the ‘eight gates and five steps’ (八门五步 - Ba Men Wu Bu) which utilise the dropping and rising force (bodyweight and qi, etc) which opens into wide spirals or is ‘pulled’ back in to a ‘still’ centre. The ‘eight gates and five steps’ represent the expert application of yin-yang interaction, and the application of advanced Taiji principles. However, without first realising and mastering the ‘still’ centre that is ‘all-embracing’ there can be no talk of perfecting the ‘eight gates and five steps’ - as the ‘eight gates and five steps’ arise solely from the mastery of the ‘all-embracing’ and ‘still’ centre. For most who learn taijiquan, however, these concepts mean nothing as they are not learned or even heard of. Simply practicing the movements of Taijiquan with no expert guidance is a fruitless task as you will remain just as ignorant ten years down the line as when you started. Study and seek instruction. Awareness is the key as a good instructor will teach a practitioner how sense their bodyweight and ‘feel’ its rebounding force. Without this – Taijiquan is just a set of meaningless exercises. This is achieved by a superficial relaxation being transformed into a profound ‘loosening’. Hard work must be a daily habit. Do not give-up and seek to achieve the maximum with the minimum. Calm the mind and expand awareness into the environment. Practice within this awareness so that mind and body unite and become one. Improve one aspect of training every day. If practice is of a good quality – then self-defence ability will manifest in an easy manner. Remember – even if the method is correct – Taijiquan might well take a long time to master. Seek good instruction. Some people say: ‘Taijiquan can't be taught, IT can only be learned by experience.’ This is because many people possess vague notions of attainting ‘enlightenment’ (悟 - Wu), but no real knowledge of how to go about achieve it. Instead, they repeat superficial movements in cycles of performance within which there exists no transforming mechanism to ‘shift’ the structure from one manifestation to another. Even at the birth-place of Taijiquan, thousands have gathered over the last one-hundred years to practice the movements of the Taijiquan style – and yet very few can a) fight with the style, b) live long lives or c) attain enlightenment through such practices. This is true even of people who learn from well-known teachers with established lineages. Over-all, this leads to a deterioration of Taijiquan ability. The secret of mastering Taijiquan in all its aspects lies with the mastering of the placement and functionality of the ‘waist’ or ‘middle gate’, for when this understanding is lacking, the entire edifice of Taijiquan ability cannot be established! Authentic Taijiquan technique, regardless of style or frame, depends entirely upon the perfection of the use of the ‘waist’. This explains why there are many references to the ‘waist’ and ‘waist management’ spread throughout the Classical literature of China. Such examples are ‘the waist is the master’, ‘the waist is the driver’, ‘the waist unites and controls the upper and lower body through the turning of the spine’, and ‘the mind’s awareness penetrates and controls the waist’ - are just a few examples of the extent of this importance. However, according to observations, many practitioners, especially beginners, are still not clear about this. Many chose to stand bolt upright, crooked or overly slanted; some do not know how to loosen their hips; others only know how to swing their arms but don’t know how to turn their waists, and their movements appear awkward and stiff. The analysis of the reasons for these errors is mainly due to an unclear understanding of the position, function and basic essentials of waist movement found within genuine Taijiquan principle and technique. The point is this - If you practice Taijiquan without training your waist, it will be difficult to improve your skills throughout your life. The author of this article would like to assist martial artists in China (and abroad) through sharing my own experience and humble insights. To sum-up the important position and function of waist movement, there are two main points:

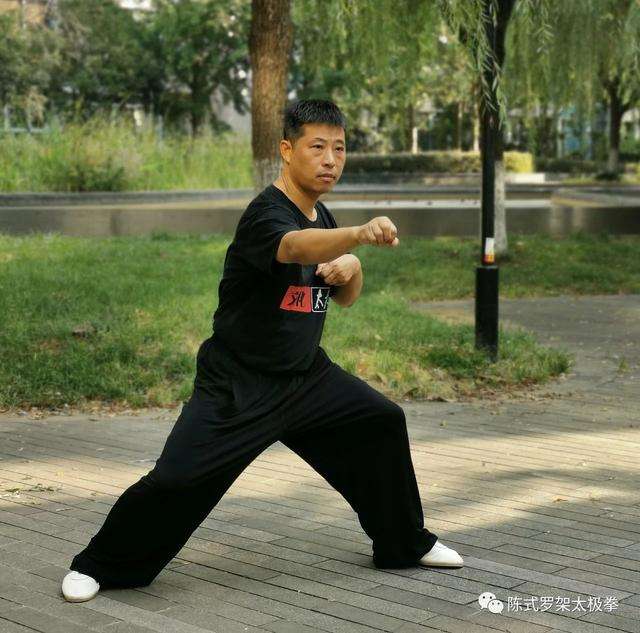

https://www.sohu.com/a/501559060_121124541 蓄劲如开弓,发劲如放箭 2021-11-17 00:00 拳谱这两句说话其实颇为形象化,是以身体作为一张弓来发劲。要点是我们自己身体要有三个根:顶根、脚根及腰根(丹田或命门)。设想顶根与脚根定点不动,腰便可自由的荡,只要每动皆双向(即有来有回),便不会破坏全身的对称平衡,时刻保持中正。 如果你用力推我,我顶根与脚根不动,腰根被你推开成开弓之势,到你力尽,我腰根的重量荡回来,便把你笔直放出去,而我自然中正,不出方向。如果我在开弓时不知不觉的围绕你转动一百八十度再发劲,便把你前推之势也加以利用,你跌得更惨! 事实上三个根只要能保持一个根不动,其余两根可来回的荡以发劲并时刻保持中正,若在贯串两个根之荡时,加上螺旋扩大或螺旋缩小,威力更大。因为我有三个根,要定那一个根由我决定,而且随时转换,你难以捉摸,「人不知我,我独知人」,一碰便胜败已分,与你转圈推手只是客气而已。 这里牵涉到用意不用力,例如顶根不动,是因为体内不断有S循环在进行而外示安逸的结果,不是用力去固定头顶。身体意气走S,是以意想推动的,以意气驱使身体而动,一点不用力,稍一用力去扭动身体四肢走S线,便是用力,不是以意气运身,没有威力可言了。太极拳的任何解说,包括拳谱,都有一个前提,就是「用意不同力」,稍一用力,那怕一点点,已经不是太极拳,这是太极拳的关键内涵,也是最难练习、最难做到的地方。 怎样做到“用意不用力” 太极拳是应用太极原理于技击的拳艺,太极拳架是为使身体熟练应用太极原理而编造的练习,所以练拳要明白练习的目的。太极拳最大的特点是「用意不用力」,不用力怎样打人呢?是借力打人,借力的来源有二,借他人之力及借自身的地心吸力,即利用体重在地面的反弹力,我们日常的习惯,唯恐站不稳,不自觉的往下压,没有利用体重反弹的习惯。 要改变这习惯,头顶要有领起之「意」,不用力,身体放松,才能引导反弹的体重上升,再下沉,又反弹上升,又下沉,又上升……,连续不断,这才是「虚领顶劲、气沉丹田」,二者是一体的,是利用体重反弹的练习。 “用意不用力”最难之处是「松」,“松”是张开,不是“弛”,是“中正安舒”。“中正”是中心与四周的关系,“动而不动”是为“中正”,所谓“动而不动”是每动则外围之动都对称平衡,使中心平稳有如不动,所以要求“有上必有下,有前必有后,有左必有右”,其实“动之则分,静之则合”是阴阳关系,是动态的对称平衡开合,由点到线、面、体的开合是为“八门”;开则螺旋开张,合则螺旋收缩,是为“五步”,能把握“八门五步”,就能利用升、沉的体重以开合收人发人。 “八门五步”是阴阳之势的应用,就是太极原理的应用。如果把“中正”当成静态,而实际上静态之中不是中,静态之正不是正,不“中正”,则难“安舒”,不“中正安舒”,则不能“松空圆活”,不“松”则借不到体重反弹,就不能“用意不用力”,更不要谈“八门五步”了,所以学太极拳都由“中正”开始。 但一般学习太极拳的,大都不明太极思维,把原则僵化了(以为“中正”是静态的中、静态的正便是僵化),一般学习“中正安舒”而未能过关,所以只能不断练习拳架,冀求有能「松」的一日,这是吃力不讨好的。多研究太极思维,练习时不断评核所练习的能否结合太极原则,不断改进,才会有进步,如果练习不能与太极原理会通,是为练习而练习,目标不清,功效有限。 感觉不到重量反弹,是身体不听话,自已用了力而不自觉,就是不能「松」。用力是日常习惯,要在不放弃这日常习惯之外,再建立一种不用力的习惯,并要听意识指挥:日常生活用力;技击时不用力,这是很难很难的训练,就算方法正确,也要很长时间的练习,何况方法不一定正确,(何谓正确方法?练习无定法,凡合乎太极原理的方法都是正确的)。 有说:“太极拳是教不会的,只能学会”,因为要点是“悟”,所教的方法是死的,要能通过方法而领悟太极原则的应用,才学得会,所以有承传也不一定出人才,过去百多年,在几个太极拳发源地,每日用功,长时间习拳的成千上万,但有功夫的代不数人。太极拳之所以慢慢变质,变成流行的健身太极操,不是没有原因的。 “太极腰”的修炼 太极拳特别注重腰部活动。经典著作中讲得很多,如“腰为主宰”“腰为驱使” “源动腰脊转股肱” “刻刻留心在腰问”等,都是说腰在太极拳运动中的重要性。但据观察,不少练拳者,特别是初学者对此还不够明确。有的立身不正,歪歪斜斜;有的不知松腰松胯;也有的只知旋臂而不知转腰,动作显得别扭、僵硬。分析原因,主要是对腰部活动在太极拳运动中的地位、作用和基本要领认识不清所致。正是:练拳不练腰,终生艺难高。笔者愿以自己的体会和浅识拙见,向拳友们讨教。腰部运动的重要地位和作用概括起来,主要有四点。 1.腰部起着承上启下、维持身体姿势和传导重力的中枢作用。 它把上体和下肢两部分紧密地结合为一个有机整体,也是比较集中地反映身法技巧的关键。它对带动和调整全身动作的变化、重心的稳定以及推动劲力到达肢体各部分都起着十分重要的作用。只要腰部一动,全身其他部位皆相适应,无有不动,形成上肢、下肢、躯干完整协调的运动。上肢运转要求转腰旋脊,以腰带臂,腰领手随;下肢运转要求以腰带胯,以胯带腿,以腿带足。因此,套路中各个拳式正确手法和步法的变换,都必须依靠腰部不停地灵活运转来完成。同时,腰部还能运丹田之气到达四肢百骸,从而形成周身完整一气。 2.腰部起着蓄势发劲作用。 拳论日:“劲起于脚跟,主宰于腰,发于脊背,达于两膀,形于手指。”又说:“掌、腕、肘和肩、背、腰、胯、膝、脚,上下九节劲,节节腰中发。”劲法中也强调,以缩腰、拧腰配合蓄劲,以舒腰、转腰配合发劲。这既是太极拳的发劲特点,也是太极拳发劲时应遵循的一条规律。因此,太极拳八种劲法虽然都形于手、臂、肩、肘,但劲力源头均发自腰部。 例如拥劲,虽然“拥在两臂”,但主要靠腰与意气相配合发出的劲力棚架对方,并借机击之。搌劲,虽然“搌在掌中”,但主要靠转腰坐胯顺势将对方引至自己下盘一侧,化解和防御对方攻势。挤劲,虽然“挤在手背”,但主要靠腰椎后弓之劲,手脚并进,合力向前挤击。按劲,先师们明确指出了“按在腰攻”,靠腰劲带动全身整劲,用双手向前按击对方。其他采、捌、肘、靠,也主要以腰腿劲为基础,加上内气的鼓荡,以全身的弹性劲、爆发力,快速准确地将对方弹出。这都充分说明腰是劲力之源。只要腰力运用得当,就可使周身力量集中于一点,战胜对方。例如野马分鬃,不论左抱右分或右抱左分,腰部旋转、腰部发出的力量都起主要作用。同时,按腰送肩还可放长两臂,延长进攻距离,有利于击打对方。 Critically Examining the ‘Fist Frame’ (拳架-Quan Jia) as the Foundation of Taijiquan Practice11/27/2021 Contribution & Translation Shifu Adrian Chan-Wyles Beginners learn Taijiquan by replicating the "fist frame" (拳架-Quan Jia) - or the ‘physical structure’ of the Taijiquan style as taught by their teacher. The teacher uses the ancient method of teaching one step and one sequence at a time, so that each student can learn each step and each sequence before moving on to the next section. The teacher ‘expresses’ each movement one by one, whilst the practitioner imitates these movements ‘one by one’ until they become natural. This process is termed the "leading frame" (领架 - Ling Jia). Although the “fist frame” defines the physical appearance of the Taijiquan style, the essential and underlying reality of these movements contains an extremely rich content. It not only contains its extensive martial application, but this body of knowledge is closely connected to the internal strength-building (内功 - neigong) exercises. Authentic Taijiquan is passed on from one generation to the next through its readily recognisable ‘fist frame’ or stylised form. It is only through the correct preservation of the “fist frame” that all the other ‘hidden’ techniques are preserved and passed-on. To effectively learn a style of Taijiquan, you must first seek out the correct “enduring image” (形象 - Xing Xiang), as taught by a reliable teacher. Logically follow the rules, be meticulous, and replicate each movement one by one and step by step. First learn the correct orientation of the body (that is, the correct alignment of the head, torso, arms, legs, hands and feet, etc), next perfect the hand positions and the techniques through which these positions are used, then perfect the footwork – learning ‘how’ and ‘when’ to step and stand-still, learn all the movement routes – that is how to step, when to stop stepping and how to piece each movement together into a smooth sequence of events, and through doing all this probably, mastery the ‘outer’ style of each style. The ‘outer’ methods are mastered first – then followed by a deepening of understanding and awareness whereby the ‘inner’ methods become apparent and are in-turn mastered. This creates a unified process which sees a relaxed mind, body and environment ‘merge’ into one complete reality of ‘awareness’ and all-embracing ‘presence’. According to whatever the style of Taijiquan being studied, ensure that the ‘chin is placed-forward (and slightly down) so that the vertebrae of the neck are gently but firmly ‘extended’ and the head correctly ‘lifted’ and placed with a ‘rooting’ strength upon the shoulders. The head and neck – in relation to the shoulders – becomes both ‘buoyant’ and yet ‘heavy’ whilst being perfectly aligned between all its constituent factors. This alignment of the vertebrae extends down from the neck into the chest and lower back area (simultaneously confirming the ‘concave’ and convex’ anatomical structures), with each placed exactly where it should be above and below all other contributing structures. The shoulders are ‘rounded’ as they surround the ‘rounded’ chest-cavity and there is no contradiction in the head-to-toe alignment of the bones, muscles, ligaments and tendons. The chested is rounded as it fills and empties with ‘air’ and ‘qi’ (氣). Therefore, the concave and ‘empty’ chest (together with the relaxed and strengthened abdominal muscles) joins the neck and head in being both ‘robust’, incredibly ‘strong’ through ‘alignment’ and yet ‘flexible’ like the wind. The pelvic-girdle is correctly aligned with the vertebrae that emerge from it. The pelvic-girdle form a ‘bowl-like’ structure into which the mass of the digestive organs sits, manoeuvre and function, etc. From the pelvic-girdle the upper body is structured and lower body touches the earth. The pelvic-girdle connects to the ground through the bone, joint and muscle structures of the legs, which always includes the connecting tendons and ligaments all over the human body! The pelvic-girdle must be rounded and concave so that it aligns with the knees, and the ankles, whilst the knees remain ‘rounded so that the bodyweight can ‘drop’ and ‘rise’ through the area unhindered. The descending bodyweight drops into the ground through the centre of the anatomical foot-structure (which varies in exact location depending upon the technique being used). When all this is ‘corrected’, then it becomes obvious that the shoulders and hips, elbows and knees, wrist and ankles and hands a feet become permanently ‘unified’ and ‘aligned’ in their physical activity and non-activity (I.e., ‘standing still’, etc). As ‘awareness’ increases, the shape of the hand and the ‘exact’ placement of one bone to another becomes possible and is a skill repeated all-over the body including throughout the structures of the feet. In other words, the ability to ‘align’ and correctly ‘arrange’ the entire body in general – becomes a highly efficient ‘localised’ skill applied to the smallest area of the body itself. This is how tremendous power can be generated throughout the ‘frame’ and correctly emitted through with a ‘fist’ or the open ‘palm’. Conversely, huge amounts of power can be ‘absorbed’ through an ‘open’ or ‘closed’ hand, distributed throughout the Taijiquan ‘frame’ and harmlessly neutralised into the environment. This is how the ‘mind’ first ‘expands’ its awareness’ throughout a ‘unified’ body-structure (or Taijiquan ‘physical ‘frame’) before ‘expanding’ beyond the physical ‘frame’ and becoming ‘all-embracing’ and ‘all-inclusive’ of ‘all’ and ‘nothing’ in the physical environment! This is the process of how a material ‘form’ (形象 - Xian Xiang) become an immaterial, ‘mind’ or spirit-driven ‘form’ (神象 - Shen Xiang). If ‘physical’ Taijiquan practice does not evolve into a ‘spiritual’ Taijiquan practice, then a life of practice, determination and sacrifice has been entirely wasted! The teacher provides the ‘fist form’ - but you must practice ‘beyond the ‘fist’ and firmly cultivate the ‘mind’. Without this transformation, nothing substantial can be fulfilled. The ‘spiritual essence’ is contained within the ‘form’ and the ‘frame’ - but is dependent upon neither and must emerge from both. However, due to the nature of the complexity of Taijiquan design and practice, it is inevitable that some will encounter problems with their practice. Beginners are often prone to rigidity of mind and body and are unable to properly ‘adapt. The most common errors involve ‘stiffness’ (僵 - Jiang), ‘scattered’ awareness (散 - San), ‘discontinuous’ awareness (断 - Duan), ‘non-alignment’ (歪 - Wai), ‘non-rootedness’ (浮 - Fu) and other problems. A) ‘Stiffness’ (僵 - Jiang) - involves ‘tension’ being hidden throughout the mind and body of the practitioner. It is a product of ‘habit’ that must be undone and countered through the practice of psychological and physical relaxation. Habits of thought that generate psychological tension must be ‘dissolved’. Simultaneously, the tension that abides within the muscle-fibres must also be ‘released’ through deep breathing and the focus of the mind’s attention upon the area. Eventually All mind-body tension (which is merely ‘blocked’ qi energy flow), must be a) ‘released’ and b) ‘reabsorbed’ into the entire mind-body system. B) ‘Scattered’ awareness (散 - San) consists of a mind that is not yet ‘unified’ into a spiritual-whole so that the physical body is also affected by this ‘disunity’. A scattered mind inevitably manifests as a scattered body in the physical realm, whereas a unified mind which is all embracive of the physical body (and environment) inevitably provides the foundation for a fully united Taijiquan form. The ‘awareness’ must be ‘united’ by focusing the mind and disciplining its functionality. Once the psychological processes are ‘united’ - then the physical body (and its actions) will be permeated by this ‘unified’ awareness. C) ‘Discontinuous’ awareness (断 - Duan), between the upper and lower body, means that there is no connection between the mind, body and environment. In other words, no ‘rootedness’ as the practitioners ‘awareness’ capacity is both incomplete and discontinuous. The upper and lowe body cannot interact in a fluid and smooth fashion. Q energy flow is ‘broken’ at crucial points (effecting ‘jing’ [精] and ‘shen’ [神] circulation, generation and transformation). As the top half of the body is ‘disconnected’ from the bottom half of the body – there is no transference of ‘awareness’, ‘energy’ or ‘ability’ through the pelvic-girdle. Beginners must observe and understand flowing water, reeling silk and clouds floating across the sky and how nature achieves these feats of action with no apparent effort at all. Human-awareness must extend fully in the ten-directions and not stop short at nine-directions! The practitioner must master the connection between ‘awareness’ and ‘movement’ - when such an awareness is ‘lacking’, then there is a ‘discontinuous’ awareness, or ‘break’ between areas of psychological and physical control. This problem can be resolved through practicing ‘deep’ relaxation of mind and body, as well as focusing the mind to ‘lead’ and ‘guide’ (引 - Yin) the awareness evenly through the physical structures of the body, so that ‘awareness’ always precedes and initiates all movement so that there is never a ‘break’ between ‘intention’ and ‘actuality’. D) ‘Learning to lead’ (引 - Yin), or direct a strengthened, concentrated and united mind so that its ‘intention’ continuously precedes all movement both ‘within’ and ‘without’ the physical body. In this regard, conscious awareness must automatically permeate the ten directions and everything within those ten directions – including the individual mind and body. This is a continuous pulsation that exists during sleep and awake times and which is fundamental and underlying in nature. Guiding the awareness, however, ss subtly different as it is a ‘refined’ awareness operating within this meta-awareness. Whereas the meta-awareness permeates the cellular structure of the mind and body – this ‘leading’ awareness penetrates the cellular wall and permeates into the subatomic structures. It has within it a compelling and attracting force which can also be ‘reversed’ into a repelling force (like releasing the built-up energy in a drawn-bow). At other times, it directs awareness and ‘pulls’ the physical body into the various directions of movement required. It is nothing short than the evolutionary mind-body nexus. ‘Thought’ within this context, although appearing ‘spiritual’ and ‘other-worldly’ is in fact a very subtle form of substrative material reality. E) ‘Non-alignment’ (歪 - Wai), refers to a disjointed and misplaced Taijiquan ‘frame’ (positioning) and ‘sequencing’ (form) so that the entire manifestation departs from the ‘law’ of the style, the philosophy of the tradition and the instruction of the teacher. Another description is that of a ‘crooked’ mind and body which mislead the practitioner and the world of taking the wrong direction. The body leans when it should be straight, or is straight when it should be leaning! The body remains ‘unrooted’ when it should be firmly affixed to the ground. The mind has no unified presence and is unable to penetrate and guide the the physical structures of the body. As there is no penetrative insight, the movements are ridiculous and disconnected. There is no awe-inspiring presence and no real Taijiquan practice taking place! F) ‘Non-rootedness’ (浮 - Fu) can also be translated as ‘floating’ and refers to the non-dropping of the ‘qi’ (and ‘bodyweight’) down into the dantian (丹田) situated two-inches below the naval and through the centre of the bones (stimulating the bone-marrow) in the case of the bodyweight proper. Pockets of psychological and physical tension can prevent the qi-energy flowing properly through the eight special channels (and the numerous other major and minor qi-energy flow channels), as well as the bodyweight ‘dropping’ effectively through the centre of the bones down into the floor through the soles of the feet, etc. Eventually, the dropping of the bodyweight results in a ‘rebounding’ force which bounces the qi-energy back up the body through the centre of the bone marrow – a gravity related processes which eventually integrates with the qi-energy flow through the qi-energy channels. If an underlying psychological awareness of the deep structures of the body is not present, then neither qi-energy flow nor bodyweight movement will be understood or even known to exist! Instead, the external body will be separated into essentially top-heavy and insular compartments of disjointed and non-rooted entities! All is disconnected from the ground and from the awareness of the mind. Drop the awareness into the ground to rescue the mind and body from this hellish existence! This is why the ‘fist frame’ is the mother of the Taijiquan system of advanced Chinese martial arts (as it conveys the ‘secret’ of how to ‘punch’ with extreme power! Each individual part of the body must be thoroughly penetrated and minutely understood with a fully develop and directed conscious mind – before each part of te body is ‘integrated’ (through accumulated ‘insight) into a ‘unified’ whole. Although a ‘form’ of Taijiquan made well hold continuous physical characteristics that continuously broadcast a well-known' style – it is the mastery of the ever-change ‘frame’ of the Taijiquan form that is vital for martial arts dominance and success in the physical world. Of course, the ‘form’ and ‘frame’ obviously over-lap and coincide but they are not identical. Whereas a ‘style’ of Taijiquan may well utilise a continuous ‘form’ or philosophical-physical approach – whilst a continuously changing, altering and adjusting ‘frame’ may be manifested by an expert practitioner. Whilst being firmly ‘rooted’ to the nourishing ground, an expert practitioner of Taijiquan is continuously manifesting the ‘root’ principles of the style, whilst also adjusting that particular ‘form’ (physical superstructure) to the conditions prevailing in the external world. A ‘fist frame’ facilitates ‘punching’ (or ‘open and closed hand techniques’ in general), whilst a ‘kicking frame’ opens the hip-area allowing for an array of ‘lifting’ or ‘floating’ leg techniques which uses the foot, knee or side of the leg-structure to ‘strike’ or ‘block’ whist standing still, or moving forward, back or side to side (although some of this activity might fall under the designation of a ‘stepping frame’ adjustment). An advanced ‘iron-vest’ frame allows for the bone structure to be utilised in a manner that deflects, absorbs or re-directs incoming energy, etc. There is even the case that suggests that the ‘frame’ of a Taijiquan style should be further adjusted as the age of the practitioner increases to counter the effects of ageing. With regards to self-defence, the body-shape, experience and motivation of an opponent will call upon the defending Taijiquan to adjust the type of ‘frame’ they manifest during hostilities. A Taijiquan ‘form’ that does not adjust its ‘frame’ (or the distance between the feet and between the hands), is then ‘stuck’ in manifesting just one particular ‘frame’. This is a common mistake today developed from a lack of properly qualified teachers. When Taijiquan was ‘liberated’ from the limitations of feudalism in 1949 – there was not readily available a suitable cadre of instructors to carry-out this advanced ‘liberating’ policy. To remedy this, it was decided that initially it was enough for the ‘copying’ of the superficial movements (I.e., ‘form’) to take place throughout China, and that over-time, as this new approach of ‘openness’ settled in (with a limited single ‘frame’), the number of qualified teachers would increase. Today, this transitional stage Is still in operation, with practitioners seeking an ever-greater depth of understanding, although association with legitimate lineage masters that are coming to light. This is a slow but inevitable process. Taijiquan – the most advanced martial art ever constructed by the human mind – has been ‘freed’ from the few exclusive lineages that once controlled its dissemination. Although lineages till exist and their practice is disciplined, the knowledge they possess in now viewed as belonging to humanity. Chinese Language Reference:

https://www.sohu.com/a/114000920_467831 拳架为学练太极拳之母!练拳易犯的几点坏毛病,快来看看自己有没有? 2016-09-09 11:29 点击上方↑"功夫太极"快速免费订阅太极养生资讯 "拳架"为学练太极拳之母[摘编] 初学太极拳应从学习“拳架”开始。即是学练老师的拳架。一招一式,逐一模仿。这一过程,称之为“领架”。拳架虽为外形,但却有极为丰富的内容。它不但含有很多技击招式,还与内功练习紧密相连。拳架是太极拳的基础,也是练习太极功夫的向导。没有拳架就无法练习太极拳。架子正确与否关系到太极拳的功夫能否练成。 学练拳架,先求形象,须循规蹈矩,一丝不苟,逐一模仿。先学基本的身法、手法、步法,动作路线,各定式的样子及要领。架子应先求开展,后求紧凑。要求全身节节放松。如某一定式,先查是否“虚领顶劲,立身中正”,是否“含胸拔背,胸空腹实”,是否“松腰落胯,圆裆扣膝收臀”;再查步法是否正确;再检查肩肘腕是否放松,是否“沉肩坠肘、塌腕舒指”;最后再检查掌形、拳形,钩手等是否正确。在“形象”的基础上再求“神象”。不但要求形象,还要求神象。如不得太极拳之神形,则练一辈子也是茫然,不成大器。若想精其技,趋大成者,非得老师拳架之神形不可。然而,由于太极拳的特点,初学者往往难以适应,易出现一些毛病,最常见的主要有:僵、散、断、歪、浮等毛病。 1 僵 就是僵硬、松不下来。练习太极拳,松为第一要义。而没有经过太极拳练习的人,身上都有僵劲。年龄越大,身体越是强壮,僵劲越大。而太极拳的动作是圆的运动,要求柔和缠绵,节节贯串,全身协调,主宰于腰。这就给练习太极拳带来很大的困难。因此,一开始,就要强调放松,练习者要有意识地使自己的身体放松。用意不用力,意松体松,内外皆松。 2 散 即神散,形散。练习太极拳要求全神贯注,心无旁骛,如果练拳时心不在焉,杂念丛生,就无法做好动作。形散一般是指动作幅度过大,没有含蓄,或者动作不协调,散了架子。练习太极拳手臂和腿要自然弯曲,不可直手直脚,要注意处处保持太极球的形态。同时注意全身的协调性,所有的动作主宰于腰,以身领手,周身一家。 3 断 指意断,劲断。动作不连续,上下动作之间断开,缺乏圆滑的过渡。太极拳要求柔和缠绵,练拳时,上动未停,下动又起,如行云流水,抽丝挂线,一气呵成,动作做到九分,意要贯到十分。而初学者往往不能很好掌握动作与动作之间的衔接问题,因此,就出现了“断”的问题。要克服这个毛病,一要注意放松,二要加强“引”的练习。即掌握“引”的规律,一般来说,引的规律是欲上先下,欲左先右,欲前先后。就是向相反的方向运动。 4 引 “引”在太极拳中有非常重要的作用,它是太极拳的精华和绝妙之处。它不但起着承上启下的作用,还关系到太极拳阴阳转换,虚实开合的变化。没有引,太极拳的动作就无法圆滑过渡;没有引,就无法实现折叠转换;没有引,劲就无法绵绵不绝。 然而,在现实生活中,许多太极拳练习者,往往忽视“引”的练习和应用。他们往往注意动作的外形是否到位,样子好不好看,而忽视了太极拳的精华。练好引的关键是用内动带动外动,心静体松,精神内固,丹田旋转,引领全身,以根节催动梢节,动作似停非停,将展未展之际,心意一动,“引”则油然而生。上动未停,下动又起,流连缱绻,无始无终。应该特别指出,引是自然而然的,是松沉的表现,不是故意做出来的。不可为了做引的动作,故意把拳打得一顿一顿的。引从外形上看,以不露痕迹为上品。 引在推手中有着极其重要的作用。两人接手后,轻轻一引,即可化解来力。能引,则能做到劲由内换。由于引的圈子很小,则可做到在不动身形的情况下化发自如,即引即发,原地风光。 因此,打太极拳需注意引的练习。只有把引练好了,才能打出太极味,才能使整套拳如抽丝挂线,绵绵不断;似长江大河,滔滔不绝。引是太极拳的细微之处,乃太极拳绣花之法,须默识揣摩,细心体悟,才能真正学到。 5 歪 指身法不正。前俯后仰,左右歪斜。练习太极拳身法以端正为本。身法端正,无所偏倚,虚灵内含,浩然之气,运于全身。初学者往往由于动作僵硬,易使身体不正。身法中正是练好太极拳的基础,千万马虎不得。 6 浮 即漂浮。太极拳要求含胸拔背,胸空腹实,气沉丹田,落地生根。而初学者往往架子忽高忽低,挺胸突臀,动作漂浮,气向上涌,头重脚轻。浮乃练习太极拳之大忌,须注意克服。 要克服上述毛病,关键要抓住“松、静、沉”三个字。无论练习何种太极拳,都要在这三个字上下功夫。因此,“松、静、沉”为练习太极拳的三字经,要把它刻在脑海中,落实在行动上。在学习老师拳架的过程中,要细心模仿,悉心领悟动作要领,发现问题及时纠正。太极拳架中包含有极丰富的内容,要掌握这些内容,需要长期反复练习才能做到。 因此说,拳架为母。练习太极拳一定要在拳架上下功夫。每天反复盘拳架,如有可能,尽量多练。同时,要不断领悟内在的东西,练悟结合,“拳打千遍,其理自现”。练习拳架有一个“从外引内,以内带外”的过程。开始时,只能外形划大圈,而后逐步产生内动,每个动作先有内动,再有外动,环环相扣,无始无终,动作沉稳,柔棉,一动无有不动,一静无有不静,内外合一,周身一家。只有这样,才能逐步提高自己的太极拳水平。 孔子曰:“人而无信,不知其可也” 意思就是说:一个练武之人要是连《功夫太极》微信都没关注,简直都不知道他是怎么练拳的.. |

AuthorShifu Adrian Chan-Wyles (b. 1967) - Lineage (Generational) Inheritor of the Ch'an Dao Hakka Gongfu System. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed