|

The Island known as ‘Okinawa’ lies off of the South-West coast of Japan - forming part of the Ryukyu Island Chain - and is expressed in Japanese (Kanji) ideograms as ‘沖縄’. This name may be deconstructed as follows: a) oki (沖) = expanse of open water b) nawa (縄)= rope or thread The name appears to be a direct description of the numerous islands that comprise ‘Okinawa’ – which are themselves a substantial (Southern) part of the larger Ryukyu Island Chain. Perhaps the geographical placement and general shape of the islands was seen from high mountain-tops, surveyed in passing ships and/or observed from upon high by those who flew in the ‘Battle Kites’ known to exist within medieval Japan. Whatever the case, the Okinawa Island Chain is said to resemble a meandering rope lying across the surface of the water. I have read that this area first became known to China under the Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) – but was not formally recognised by the Imperial Court until the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). This is when diplomatic and cultural contact with the King (of what was then termed the 'Liu Qiu' [琉球] Islands) was established - known today by the Japanese transliteration of 'Ryukyu'. 琉 (liu2) = sparkling-stone, jade, mining-stone (from previously uncultivated land), precious-stone, arriving, and breaking through (to a place far away - and situated on the fringes of the known world) 球 (qui2) = beautiful-jade, polished-jade, refined-jade, jade percussion instrument, earth, ball, and pearl. The Chinese Mariners must have been taken with the beauty of the Ryukyu Islands - as the term '玉' (yu4) – or ‘jade’ - appears as the dominant left-hand particle of both ideograms forming the name ‘Liu Qiu’. From the Tang Dynasty onwards, the Liu Qiu Islands were considered a distant (but important) part of the Tributary System of Imperial China. In return for a continuous show of annual respect (usually in the form of expensive gifts and/or elements of trade, etc) China shared her extensive culture. It was not until 1872 CE, however, that Imperial Japan took decisive action to annex all of the ‘Ryukyu’ Islands – and it was around this time that the term ‘Okinawa’ was developed to describe the Southern two-thirds of the Ryukyu Island Chain – now a ‘Prefecture’ of Japan. This history explains why the ideograms for ‘Okinawa’ are written in (Japanese) ‘Kanji’ - and are not obviously ‘Chinese’ in structure (as is the far older name of ‘Liu Qiu’). Is it possible to ‘reverse-engineer’ the Kanji ideograms associated with the name ‘Okinawa’ (沖縄) and work backwards as it were – to the original Chinese ideograms? The answer is ‘yes’ – as such an exercise might well shed some more light on the meaning of the name itself. Japanese - 縄 (nawa) = Chinese – ‘繩’ (sheng2) When adjusted in this manner - the Japanese name of ‘Okinawa’ (沖縄) is rendered into the Chinese language as ‘Chongsheng’ (沖繩). Whereas the first ‘Kanji’ ideogram of ‘沖’ (oki) remains identical with its Chinese counterpart of ‘沖’ (chong) - the second ‘Kanji’ ideogram (縄 - nawa) undergoes a substantial modification (繩 - sheng). From this improved data a more precise definition of the name ‘Okinawa’ can be ascertained through the assessment of the Chinese ideograms that serve as the foundation of the Kanji ideograms – working from the assumption that this meaning is still culturally implied through the use of ‘Kanji’ in Japan – even if such a meaning is not readily observable within the structure of the ‘Kanji’ ideograms themselves. 沖 (chong1) is comprised of a left and a right particle: Left-Particle = ‘氵’ which is a contraction of ‘水’ (shui3) – meaning water, river, flood, expanse of water, and liquid, etc. Right-Particle = ‘中’ (zhong1) refers to the concept of something being ‘central’, in the ‘middle’, or being perfectly ‘balanced’. It can also refer to an ‘arrow’ hitting the ‘centre’ with a perfect ease. Therefore, the use of 沖 (chong1) in this context - probably refers to an object that centrally exists within a body of water. 繩 (sheng2) is comprised of a left and right particle. Left-Particle = ‘糹’ which is a contraction of ‘糸’ (mi4) – meaning something that resembles a ‘silken thread’, a ‘thin’ and ‘flexible’ cord, a ‘rope’ or ‘string’, etc. This may also refer to the act of ‘weaving’ or to an object (like a rope, string, or strand) which is ‘woven’ into existence – perhaps implying a ‘cohesion’ attained through an ‘inter-locking’ agency, etc. Right-Particle = ‘黽’ (meng3) – this was originally written as a depiction of a type of frog – but evolved to be used generally to describe the act of ‘striving’, ‘endeavouring’, or ‘working hard’ (nin3). However, I am of the opinion that more practical attributes are at work in this instance. An old (but simplified) version of this ideogram is ‘黾’ – which demonstrates a clarification of what used to be a ‘frog’: This explains why there is said to be an ‘upper’ and ‘lower’ element to this particle: Upper-Element = ‘口’ (kou3) – signifies an ‘open mouth’, ‘entrance’, ‘mouth of a river’, and ‘port’. This can also denote a ‘boundary’ and a ‘hole’ or ‘indent’. This used to represent the head of a frog. Lower-Element = ‘电’ (dian4) – denotes ‘forked-lightning’, ‘energy’ and ‘electricity’, etc. Although evolving from the body of a frog – this element conveys not only the overt power of lightning – but perhaps retains something of the ‘shape’ of forked lightning in its usage as a noun. Perhaps 繩 (sheng2) is a descriptive term used to describe a port that allows entry to a string of islands which seem to take the shape of a rope that geographically unfurls - like forked lightning traversing the sky. Conclusion The term ‘Chongsheng’ (沖繩) – or ‘Okinawa’ - probably refers to a string of islands (and ports) which exist within a broad expanse of open sea - like a rope floating upon the surface of the water (the shape of which resembles that of forked-lightning). This place may be difficult to reach – and the people encountered may be very hard working. It is highly likely that these islands seem to float like a frog on the surface of the water – hence the selection of these ideograms. Of course, the post-1872 Japanese Authorities chose to use the Kanji ideograms of ‘沖縄’ to convey the concept and meaning of the name ‘Oki-Nawa’. In Chinese language texts, I do not see Okinawa referred to as an isolated unit of geographical description. This is because Chinese literature refers to the entire Chain of Islands by the far older and more traditional name of 'Liu Qiu' (琉球) – which was politically acknowledged through ancient diplomatic exchange. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that the post-1872 Japanese Authorities did not abolish this Chinese name – but borrowed it – simply transliterating it into the now well-known ‘Ryukyu’ Islands. Okinawa is only around two-thirds of the Southern-Central area of the Ryukyu Islands – but as far as the ancient Chinese were concerned, the ‘King of Ryukyu’ was the ‘King’ of the entire geographical area defined by this term. Whereas the Chinese term is prosaic (poetically speaking of ‘jade’ and ‘unexplored’ land – the Japanese term might well be practical as it seems to be describing the ‘rope’ that is extensively used in sailing ships, boats, and other floating entities – including the requirement to ‘moor’ such objects in purpose-built ports. The difference in the two-names probably reflects the developing socio-economic conditions prevalent throughout the Island Chain at the time of conception – with around 1500 years separating the development of the two names. Chinese Language Text:

0 Comments

Dear Tony Interesting. Thank you for your knowledgeable explanation of sparring - an adult 'tiger playing with a cub'. This inspired me to research 'Ran-Dori' in Japanese-language sources - which is written as '乱取り' - '乱捕り' and 'らん‐どり'. Both of the following Japanese-language Wiki-entries (I have checked the data is correct) should be read side by side to gain an all-round clarity - as the 'Randori' entry does not specifically mention Karate-Do - whilst the 'Kumite' page explains that in some Styles of Karate-Do - 'Kumite' is referred to as 'Randori'. Randori - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate) Kumite - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate) I suspect the inference is that in Okinawan Karate-Do the term 'Randori' is used - whilst in Mainland Japan - the term 'Kumite' is the preferred. Difficult to say, but as you know, 'nuance' and 'implication' is an important part of Japanese communication. What is NOT said is as important (sometimes more so) than what IS said. Perhaps this Yin-Yang observation is just as important for sparring - whatever its origination and purpose. As for the traditional Japanese and Chinese ideograms - this is what we have: 乱取りand 乱捕り 乱 (ran) = chaos, disorder 取 - 捕 (to) = take hold of, gather, control, arrest り(ri) = logic, reason, understanding Therefore, 'Ran-Tori' and 'Ran-Dori' are synonymous - with the concept expressed in its written form as '乱-取り' - ot 'Chaos (Random Movement) - Seize Control of'. What is 'chaotic' in the environment is wilfully taken control of - by imposing an outside order upon it. This suggests that the 'non-controlled' is 'controlled' by the structure of Kata-technique - which is brought to bear by an expert. There also seems to be the suggestion that that which 'moves' - is wilfully brought to 'stillness'. As for a Chinese-language counter-part, perhaps we have: 乱 - 亂 (luan4) = disorderly, unstable, unrest, confused and wild (Japanese = 'turbulent') 取 (qu3) = take hold, fetch, receive, obtain and select り- 理 (li4) = put into order, tidy up, manage, reason, logic and rule It would seem that the Japanese term of 'Ran-Dori' equates to the Chinese term of 'Luan-Quli' - or 'Disorder - (into) Order Rule'. Your reply inspired me to think about what the Japanese '乱' (Ran) - or Chinese equivalent '亂' (luan4) - actually means. What is the definition of the 'disorder' being referenced to when 'Ran-Dori' is being discussed? Therefore, '亂' (luan4) is comprised of a 'left' and 'right' particle: Left Particle = 𤔔 (luan4) means to 'govern' and 'control' - and is structured as follows: a) Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. b) Lower (Inner) Element = 幺 (yao1) - a contraction of '糸' (mi4) which refers to 'thin silk threads'. c) Lower (Outer) Element = 冂 (jiong1) this is a 'comb', 'beater' or 'heddle' - a device to 'order' the silken threads that require weaving. In normal usage, this ideogram denotes the structured boundary that clearly demarks the city limits. Right Particle =乚 (yi3) is a contraction of '隱' (yin3) - meaning to 'hide', 'conceal' or 'cover-up', etc, as in 'something is missing'. It can also refer to a required process that is 'profound', 'subtle' and 'delicate' - but which is currently 'lacking'. It may also mean 'secret' and 'inward' or 'inner', etc. I would say that 'obscuration' is what this ideogram refers to in its meaning. Conclusion The literal meaning of '亂' (luan4) [or 'Ran' in 'Ran-dori] - is that it refers to a lack of skilful organising ability (disorder and confusion). The thin silk threads are not placed correctly on the wooden frame (loom) - and therefore cannot be 'weaved' together in an orderly fashion. This entire process lacks the required profound knowledge and experience to achieve the objective - thus the hands (and body) cannot be used in the appropriate manner. Ran-Dori (乱捕り), as a complete process, suggests that it is the opposite of the above 'lack of skill' that is require in sparring. Not only is this skill required, but 'ri' (li) element (理 - li3) - suggests a 'regulation' and an 'administration' (premised upon logic and reason) - such as the profound skill required to 'cut' and 'polish' jade. I was discussing Randori with another language expert and they gave me more data which I have added to this paragraph: 'Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. ' I was curious as to why the two hands were so specific in their orientation and my colleague said that they are clearly carrying out the process required for ancient 'weaving'. One hand is laying the 'warp' - or 'vertical' thread down through the loom - whilst the other right hand is performing the function of 'weaving' multiple 'weft' threads into place horizontally across the loom! As a matter of comparison - the 'Kumi' (組) in Kumi-te (組手) - Chinese 'Zu Shou' - means to 'weave continuously'. This translates as 'to be skilful' (the silken threads are skilfully woven [糹-si1] together forever - like the longevity of a sacrificial vessel [且 - qie3] - which are traditionally made out of stone). Therefore, Kumi-te literally refers to a 'continuous skill that unfolds through the hand'. This may be compared to the term 'Ran-Dori' which refers to a 'missing skill' that has yet to be 'acquired' and is in the midst of 'being acquired' (through developmental training) - whilst Kumi-te implies that the required skill is already present and should manifest automatically.

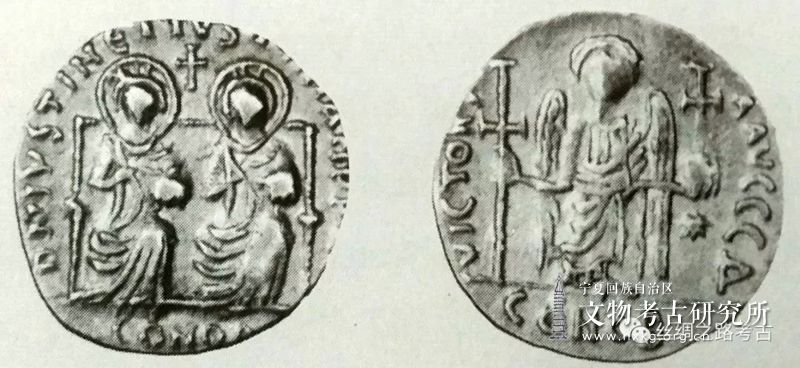

Historical Contextualisation: How 4th Century CE Roman Coins Found Their Way to Okinawa! (7.9.2022)9/9/2022 The earliest Western mention of ‘China’ (as ‘Seres’ - Greek for ‘Land of Silk’) seems to be in the 4th century BCE work of the Greek physician and historian ‘Ctesias’ (Κτησίας) of Cnidus (now in Turkey) who was born c. 416 BCE. This is described in the 2008 Chinese language book entitled ‘中国与罗马 - Zhong Guo Yu Luoma) or ‘China and Rome’ written by the esteemed Mainland Chinese academic Qui Jin (丘进). In a book of anecdotes describing the inhabited regions of the world, Ctesias is quoted as saying, ‘The people of Seres and North India are said to be strong and tall in stature! It is said that some can grow as tall as 13 cubits! (a single ‘Coudee’ or ‘Cubit’ = approximately 0.5m). It is not uncommon for these people to live for 200 years!’ ‘赛里斯人和北印度人身材高大,甚至可以发现某些身高达13肘尺(Coudée,约合0.5米)的人。他们可以寿逾200岁。’ The modern science of archaeology – when applied around the world - tends to support the idea that both China and the Greek and Roman worlds possessed vague and hazy ideas regarding one another’s existence certainly during the early centuries BCE. We are on firmer ground during the year 97 CE, when it is recorded that the Eastern Han Dynasty of China attempted to send an emissary - named ‘Gan Ying’ (甘英) - to Rome but that his journey was blocked by the Parthians. Han Dynasty records further state that the Roman emperors Antoninus Pius (86-161 CE) and Marcus Aurelius (121-180 CE) both sent envoys from Rome to China. In the case of the latter, the Roman emissary reached China in 166 CE – landing at a place called ‘Rinan’ (日南) County before being escorted to Louyang! The Han Dynasty and the Roman Empire, however, conducted commercial trade prior to making direct political contact from around the 1st century CE (through third parties and middlemen, etc) using the maritime and land-based Silk Roads. The Han Dynasty exported fine silk to Rome, whilst the Romans exported glassware and equally high-quality clothing fabrics to the Han Dynasty. This early history is relevant when considering the interesting historical finds announced in the Japanese press during 2016! Around September 26th, 2016, The Japan Times (and many other publications) broadcast the story that Japanese archaeologists had been conducting exploratory excavations (since 2013) within the grounds of the ruined Katsuren Castle in Okinawa (which had existed between the 12th-15th centuries CE) located near Uruma City. On this day, however, things were a little different as Japanese archaeologist - Toshio Tsukamoto it was announced - had discovered four badly worn copper coins (measuring between 1.6 and 2 cm in diameter) thought to have been minted at in ancient Rome at some point during the 4th century CE. Hiroki Miyagi, an archaeologist at Okinawa International University, explained: "Katsuren Castle belonged to the Ryukyu Kingdom during the 14th and 15th centuries and was the only channel for trade between Japan and China. At that time, East Asian merchants mainly used Chinese ‘square-hole’ (方孔 - Fang Kong) money as currency, and Western currency was unknown in this part of the world. If Roman-era coins were circulating in Japan, it is speculated that this ancient currency may have flowed into the Ryukyu Kingdom from China or Southeast Asia.” It was also reported that one 17th century CE Ottoman Empire coin had been discovered during the ‘dig’, together with five other metallic objects also thought to be coins. Of course, what Hiroki Miyagi falls to mention is that when these coins were thought to have been deposited on the island - ‘Okinawa’ (or more properly ‘Liuqiu’) was part of China and not part of Japan! It was only from 1609 onwards following the Satsuma invasion that ‘Liuqiu’ became nominally a part of Japan – whilst its three Kings continued to send tribute to the Chinese emperor out of respect. It was only with the 1879 ‘annexation’ of ‘Liuqiu’ (and the surrounding islands) by the Imperial Japanese Army that ‘Liuqiu’ was renamed ‘Okinawa’ and the island chain it is a part of became known as ‘Ryukyu’ (the Japanese pronunciation of ‘Liuqiu’). When did ‘Liuqui’ become a distant part of the Chinese empire and when was this small island integrated into the umbrella that it is Chinese culture? Sui Dynasty (581-618 CE) records mention contact with an island referred to as ‘Liuqiuguo’ (流求國) - or the ‘Flow Attract’ Country (perhaps suggesting a country the tides of the South China Sea will take you toward quite naturally). This is recorded in the: a) ‘Sui Dynasty Historical Records’ (隋書 - Sui Shu) – with the relevant data entered as follows: b) Volume 81 - ‘Eastern Barbarian – List of Histories and Descriptions’ (東夷列傳 - Dong Yi Lie Chuan) c) Chapter 29 - ‘Chen Ling Biography’ (陳稜傳 - Chen Ling Chuan) c) Chapter 46 - ‘Flow Attract Country History and Description’ (流求國傳 - Liu Qiu Guo Chuan) d) Chapter 64 - ‘List of Histories and Descriptions’ (列傳 - Lie Chuan) This history records (and details) the Sui emperor ‘Yang’ (煬) [569-618 CE] who reigned 604-618 CE – and his mounting of a successful seaborne expedition to attack and conquer the distant island known as ‘Liuqiu’. Liuqiu (pronounced ‘Ryukyu’ in the Okinawan and Japanese languages) lies around 500 miles due East of the coast of Fujian province. This was not an act of wanton aggression upon the part of the Chinese State – but rather a policing action whereby Chinese villains and rebels had fled China and were carrying out pirate activities and other disruptive endeavours. Although some scholars have tried to suggest these records are discussing the island of Taiwan, the academic consensus is that Taiwan is far too big and far too close to Mainland China to serve as a safe haven for fleeing Chinese bandits, and is so close to the Chinese Mainland, that it does not fit the description of the difficulties the Chinese fleet had locating and navigating its way to the island of ‘Luiqiu’! Furthermore, no one in Taiwan had heard of the Chinese descriptive term of ‘Liuqiu’ - whereas in Okinawa the local people have referred to their island as ‘Ryukyu’ (‘Liuqiu’) for centuries! The Sui Dynasty Historical Record States: 1) 607 CE - During the second month of the third year of the reign of emperor Yang (607 CE) – the Cavalry Commander Zhu Kuan (朱寬) was ordered to travel eastward to visit and make contact with the people of ‘Liuqiu’! Due to the language barrier, however, all that was achieved was the kidnapping of one local person who was forcibly returned to China! 2) 608 CE - During the fourth year of the reign of emperor Yang (608 CE) - Cavalry Commander Zhu Kuan was ordered to lead a military expedition and invade the ‘Liuqiu’ island – but he refused to obey the order and instead ‘returned his cloth armour’! 3) 610 CE - During the sixth year of the reign of emperor Yang (610 CE) – a very large seaborne military expedition (consisting of 10,000 soldiers) was launched from Mainland China – led by General ‘Chen Ling’ (陳稜) and Senior Minister ‘Zhang Zhenzhou’ (張鎮州) - which was successful in traversing the rough seas, finding and landing on ‘Liuqiu’ island – where the local forces were met in combat and defeated! Thousands of men and women were captured and returned to Mainland China. 4) It is said that this third militarised seaborne expedition was the consequence of Chinese rebels that had: a) Defied and opposed the Sui Dynasty emperor before fleeing to ‘Liuqiu’, before b) Being pursued, confronted, apprehended and finally returned to the Mainland China to face trial. The Chinese name ‘Liuqiu’ was used during the Tang and Song Dynasties (referring to the Ryukyu Islands) and was even retained during the Islamic Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368 CE). Although ‘Liuqiu’ (流求) was retained as a place defined as being under the influence of the Chinese cultural umbrella – the Yuan Dynasty - however, altered the spelling of the name to the similar sounding ‘琉求’ (Liuqiu). This changed the usage of the traditional first ideogram of ‘流’ (liu2) [meaning ‘flow’ or ‘tradition’] and replaced it with the new ideogram of ‘琉’ (liu2) [which means ‘precious’]. This was only a very slight change – adding the beautifying particle ‘⺩’ (yu4) meaning ‘jade’ to the left-hand side of the ideogram – a typical Islamic gesture of respect and good will. Despite this recognition, the treacherous seas separating Mainland China from ‘Liuqiu’ meant that communication was spasmodic. Even though Japanese envoys routinely visited China – it was clear that the ‘Ryukyu’ Island were not considered part of Japan by the Japanese themselves - certainly not prior to the 17th century. All of this background information is required if the 2016 discovery of Roman coins on the island of Okinawa is to be properly contextualised and understood. During 1372 CE, the Ming emperor ‘Taizu’ (太祖) sent his envoy – Yang Zai (楊載) - to ‘Liuqiu’ to formalise diplomatic relations. King Zhongshan (中山 ) of the Ryukyu Islands agreed that a regular ‘Tribute’ (貢 - Gong) should be paid to the Chinese Court in exchange for military protection, political affiliation and cultural exchange (all favouring the Ryukyu people). A major problem hindering this arrangement was a) the distance of around 500 miles one way, and b) the unpredictable and terrible weather and rough seas! The Chinese Court attempted to solve this issue in 1392 CE by despatching the so-called thirty-six families (or ‘name clans’) from various areas of Fujian province to be resettled on the ‘Liuqiu’ island. This probably amounted to hundreds of men, women and children who were settled at a place termed ‘Kume Village’ or the ‘Chinese Village’. These people were chosen for their skills in growing, harvesting and sustaining forests (for producing wood), ship designing and ship building, as well as ship navigators and pilots! The purpose of this relocation was to establish efficient, open and permanent sea-lanes between ‘Liuqiu’ and Mainland China (mainly with the adjacent Fujian coast). With these people came many other important arts and crafts – including house building, animal husbandry, Chinese medicine, farming and various forms of Fujian martial arts. Of course, Chinese martial arts had been deployed on ‘Liuqiu’ since 607 CE, and it is thought a general transmission of these arts were made to the island from that time onward. As ‘Liuqiu’ people were considered ‘Chinese’ in the political sense, then in all likelihood it is plausible to assume that Mainland Chinese soldiers stationed on ‘Liuqiu’, and Chinese migrants living in ‘Liuqiu’ were willing to teach their martial arts to individuals outside of their immediate families (probably more so in the case of soldiers). From 1392 CE onwards, however, the Chinese settlers on ‘Liuqiu’ were acting under orders to relay as much Chinese cultural knowledge as possible to the local ‘Liuqiu’ people. This arrangement existed for 217 years without interruption until the Japanese ‘Satsuma’ invasion of the ‘Ryukyu’ Islands in 1609 CE! There was intense military resistance from the local ‘Chinese’ and indigenous ‘Liuqiu’ people – but being so far from Mainland China (and so close to Mainland Japan) the local inhabitants were eventually defeated. This development led to a dual influence operating on on ‘Liuqiu’ which involved the local population still voluntarily sending tribute to China – whilst nominally acknowledging a political association with Japan. This situation persisted for another 270 years before the modern soldiers of Imperial Japan invaded and annexed ‘Ryukyu’ - renaming the island ‘Okinawa’ and ‘banning’ any and all ‘Chinese’ cultural influence! From 1879 onwards the ‘new’ history of Okinawa sought to downplay, negate and expunge the extensive cultural input China exercised over the development of ‘Liuqiu’! This poat-1879 negative attitude toward China is very different to the respect and deference once shown by many Japanese people from the Sui Dynasty onwards, including the 13th century Japanese Zen Buddhist monk known as ‘Dogen’ [道元 - Dao Yuan] (1200-1253) - as recorded in his magnus Opus entitled the ‘Shobogenzo’ (正法眼蔵 - Zheng Fa Yan Cang) - which records his travels to China and respectfully represents the Chinese cultural education he received, valued and preserved! What this suggests is that a) ‘Liuqiu’ was not considered part of Japan until the late 19th century despite an unconvincing Satsuma claim in the 17th century – which was half-hearted at best – and b) neither ‘Liuqiu’ nor Japan were part of any known ancient pathway or trade route which would have linked these areas with 4th century CE Rome! At least not officially, although accidental shipwrecks cannot be totally ruled out. This is important as many of the 2016 news stories edge toward the idea that ‘Okinawa’ (as an active and prominent part of ancient Japan) was part of a ‘hidden’ or otherwise ‘obscure’ ancient trade route that neither ‘Rome’ (nor any other major participant) bothered to name or record in their otherwise extensively kept trade histories! In other words, there is no known or recorded ancient trade route which linked Japan (much less ‘Liuqiu’) to 4th century Rome! The earliest mention of what is thought to be ‘Liuqiu’ (Ryukyu) is in 607 CE, although there is some debate about whether this might refer to the island of Taiwan. If this is not ‘Liuqiu’ (Ryukyu) then it is not until 1372 CE (during the Ming Dynasty) that ‘Liuqiu’ (Ryukyu) is mentioned. This is 765 years later and would imply that ‘Liuqiu’ (Ryukyu) remained obscure and isolated for far longer than first thought! To add another layer of uncertainty to this issue, it is also true that toward the end of the Ming Dynasty, The Northern part of Taiwan was known as ‘Xiao Liuqiu’ (小琉求) or ‘Small Liuqiu’ with what is today known as ‘Okinawa’ being referred to as ‘Da Liuqiu’ (大琉求) or ‘Great Liuqiu)! Even so, the balance of probabilities suggest that the 607 CE (and after) encounters strongly suggest that the current Okinawa was the location of the Chinese seaborne expeditions, particularly when it is considered that the island nation itself possessed ‘three Kings’ - a point of historical fact certainly not attributable to Taiwan! If the date ‘607 CE’ is the time that ‘Liuqiu’ (Ryukyu) enters the history books, then this is 270 years after the death of the Roman emperor – Constantine I (272-337) - also known as ‘Constantine the Great’. When all this information is considered, what were these Roman-era coins doing in the foundations of a ruined ‘Liuqiu’ castle? The thirty-six families that relocated in ‘Liuqiu’ from Fujian province must have resulted in hundreds of people suddenly arriving on the island and establishing a settlement from 1392 CE onwards. Perhaps Roman coins had found their way to Fujian province (the gateway to China for centuries) and had become symbols of good luck to be placed in prominent places. Japanese language sources state that the four Roman-era coins were discovered within the 14th and 15th century layers of the ruined foundations of Katsuren Castle – which was destroyed in 1458 CE during internecine fighting. These layers of excavation coincide with the arrival of highly skilled Fujian migrants from the Mainland of China. I suspect these 2016 Roman coin finds were deliberately dropped into the foundation of Katsuren Castle by the Fujian Chinese migrants (for good luck) when they were helping to build and/or repair the structure (as there is a disagreement within Japanese academia as to exactly ‘when’ the castle was ‘built’ and started ‘functioning’)! The point I am making is that ‘Liuqui’ was part of China during this part of its history and so these Roman-era coins, regardless of how they arrived in ‘Liuqiu’, were in a remote part of ‘China’ and not an external ‘Prefecture’ of Japan. Between 1897-2000 CE, forty-six (Byzantine) Eastern Roman Empire (330-1453 CE) coins were discovered in China (mostly in old tombs but occasionally already held in museums or as artefacts under private ownership). To date, there has now been over fifty (ancient) Roman coins discovered throughout China, all mostly gold and belonging to the earlier Byzantine Roman period (these gold coins begin to appear in a significant number during the 6th century CE, with copper and Sassanid silver preceding). A few examples of the finds of Roman coinage in China include: a) 1895: At the end of the Qing Dynasty, Westerners obtained sixteen Roman copper coins in Lingshi County, Huozhou, Shanxi Province, which were cast from the time of the Roman emperor Tiberius (42 BCE–37 CE) to emperor Antoninus Pius (86-161 CE). Technically speaking, these finds cover the periods of the ‘Roman Republic’ (509-27 BCE) and the ‘Roman Empire’ (27BCE-395 CE). b) 1953: It is ironic that ‘Liuqiu’ first enters the written history books during the Sui Dynasty of China, as in 1953 Chinese archaeologists unearthed a gold ‘Justin II’ (d. 578) Roman-era coin, minted during the early (Byzantine) Eastern Roman Empire (330-1453 CE) period and discovered in the Sui Dynasty tomb of ‘Dugu Luo’ (獨孤羅) [534-599]! This tomb was situated in a small village of ‘Dizhangwan’, near the city of Xianyang in Shaanxi province. c) 1961: A replica gold coin featuring the image of the Eastern Roman Emperor Heraclius I (575-641 CE) was discovered within a Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) tomb located in Tumen Village in the Xi'an (Chang’an) area of Shaanxi province. d) 1977: Whilst excavating the Eastern Wei Dynasty (534-550 CE) tomb of the Official ‘Li Xizong’ (李希宗) [501-540] situated in the Zanhuang County area of Hebei - a Roman coin featuring the portrait of ‘Theodosius II’ (401-450 CE) was discovered - an emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire! e) 1977: The same dig at the Tang Dynasty tomb site in the Zanhuang County area of Hebei – there were discovered two gold coins featuring the co-rulers of emperor ‘Justin I’ (450-527 CE) and his ‘nephew’ (Justinian) - who would eventually become emperor ‘Justinian I’ (482-565 CE). f) 1978: At a dig in the Ci County area of Hebei province, a Roman gold coin was found in the tomb of Princess ‘Linhe’ (邻和) [538-550 CE] of the Eastern Wei Dynasty (534-550 CE). This Roman coin dated to the reign of emperor Anastasius I Dicorus (431-518 CE) of the Eastern Roman Empire! The coin is 17.6 mm in diameter, 0.54 mm thick, and weighs 3.1 grams. g) 1998: During early June in the Guyuan County area of Ningxia (near Gansu province), a Roman coin dated to the reign of emperor Anastasius I Dicorus (431-518 CE) of the Eastern Roman Empire was found on farmland! The coin is 17.6 mm in diameter, 0.54 mm thick, and weighs 3.1 grams and was discovered alongside fragments of a yellow-glazed porcelain flat pot. h) 2000: A farmer from Anbian (安边) Town was out tending his fields in Dingbian County, Shaanxi province, when he discovered an early Eastern Roman Empire (330-1453 CE) gold coin that had been welded onto a metal ring. The date and Roman emperor could not be discerned due to the corroded state of the artefact. The copper coins discovered in Okinawa in 2016 are very badly worn and difficult to read, but it is believed they belong to ‘Constantine I’ (227-337 CE) and he ruled over the ‘unified’ Roman Empire (27BCE-395 CE). My view is that Fujian province, as a gateway into China, probably experienced a wealth of foreign goods, artefacts and many different types of currency. I suspect the hundreds of people who comprised the thirty-six Fujian clans of China carried with them tons of equipment, weapons, tools and all sorts of everyday and cultural objects – as well as various forms of paraphernalia – to build a new life on the island of ‘Liuqiu’ from 1392 CE onwards. Although Kasturen Castle on Okinawa is sometimes reported as existing between the 12th-15th century, there is still much debate about the exact date within Japanese archaeology, with many experts stating that the castle only existed between the 13th or 14th centuries before being destroyed in 1458 CE. One possibility missing in all these narratives is that the local Chinese population, many of whom were experts in construction of one sort or another, participated in the planning, designing, constructing and maintaining of Kasturen Castle. If this did happen, then I would suggest that a number of ‘foreign’ copper coins were placed in the foundation when the castle was being built, rebuilt or extended, etc, by the local Fujian (Chinese) population who were following a common practice back in their home country! Archaeology demonstrates that these ‘foreign’ coins were believed to possess some type of magical value in the afterlife whilst being placed in the tombs of the nobility, whilst ordinary Chinese people thought of these coins as objects of ‘feng shui’ (風水) or ‘wind’ and ‘water’ significance in the maintaining and augmenting of the natural flow of energy throughout the environment. What better way of ensuring the ‘safety’ and ‘strength’ of a fortified building than giving it a semi-magical ‘boost’ in the fulfilment of its defensive design capabilities. It is entirely plausible that ever since Roman envoys started landing on the coast of China during the 2nd century CE - it was Fujian province they were making first contact with, and it is through this interactive capacity that a number of Roman coins bearing the portrait and Latin mottoes of ‘Constantine I’ came into the possession of ordinary Fujian people. By latter generations laying these Roman coins in the foundations of Kasturen Castle – they were fulfilling part of their imperial duties which involved educating the ‘Liuqiu’ inhabitants in ALL aspects of Chinese arts and sciences – with ‘feng shui’ (geomancy) being viewed as being very important at the time – certainly as important as the ability to build seaworthy ships, fight properly or to understand and apply Chinese medical knowledge correctly! Chinese Language Sources: Japanese Language Sources: English Language Sources:

|

AuthorShifu Adrian Chan-Wyles (b. 1967) - Lineage (Generational) Inheritor of the Ch'an Dao Hakka Gongfu System. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed