|

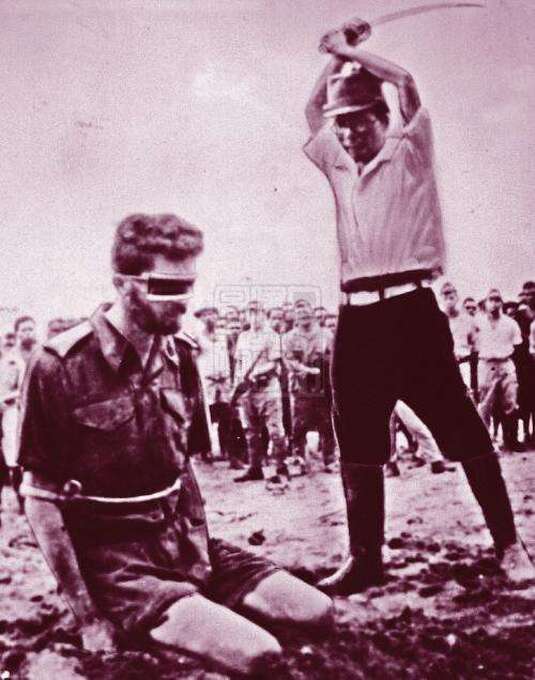

Within the Movie ‘Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence’ a Japanese POW Camp Commandant decides that the prison population of European (military) inmates are ‘spiritually lazy’. When being beaten or made to stand for hours in the sun had not altered this situation, the Japanese Officer decided that the Camp population would undergo the Shinto ritual of ‘Misogi’ (禊) – in this instance – involving a 24-hour fast-period of no eating or drinking. This is despite the daily ration being intolerably low to start with. Most prisoners – even the stronger men – were on the brink of starvation. The Japanese Officer (Captain Yanoi) – by further depleting the starvation rations - would also adhere to this ritual of ‘fasting’ whilst traditionally dressed - and sat in meditation in the Camp ‘Dojo’. This is the pristine training hall used by the Japanese Officers for martial arts and spiritual practice (a mixture of Buddhist and Shinto spiritual traditions). Similarly, in the book ‘Empire of the Sun’ written by JG Ballard – the (civilian) POW Camp (Assistant) Commandant (Sergeant Nagata) occasionally orders Chinese vagrants (often women and girls) to be ‘beaten to death’ by Japanese soldiers wielding wooden clubs. The actual 'Commandant' - Hyashi - was in fact a 'civilian' and a careerist diplomat who tended to only interfere in Camp daily activities if absolutely necessary. Obviously, Hyashi never interfered in Nagata's brutality. These starving Chinese people sit patiently outside the POW Camp waiting to see if they will be allowed in to receive a portion of the already meagre rations. The women and girls are often raped by the Japanese guards before the Camp populace of British people are assembled to watch the unfolding ritual of ‘despatch’. Sergeant Nagata believes the British POWs are ‘spiritually lazy’ and seeks to stimulate their individual (and collective) ‘ki’ (氣) flow. This ‘life force’ not only flows through each individual body – but also through the entire Camp. As Sergeant Nagata believes the Chinese people to be an ‘inferior race’ – their brutal murder (achieved through a demonstration of ‘Japanese’ manly vigour) – will ‘release’ the ‘ki’ from their (broken) bodies and supplement that available throughout the Camp. The two primary Shinto rituals on display in both of the above examples are: 禊 (Misogi) – Purification (Cleansing) of the inside and outside of the mind and body. 祓 (Harae) – Purification (Exorcism) of corruption out of the interior of the mind and body. As this ‘Kanji’ is in fact comprised of ‘Chinese’ ideograms, I can read these characters and give some type of explanation as to what these rituals are supposed to represent – at least in a historical context. I say this as the rubric of Japanese ‘spiritual’ fascism distorted (for decades) rituals and practices that would normally not have been so severe or murderously brutal. Bear in mind that within ten-years of WWII being over – Western students of Judo, Kendo and Karate-Do were avidly volunteering to undergo these rituals – albeit in a non-war setting. Nevertheless, the rituals that the Imperial Japanese used to torture and murder millions of Western and Asian people – are today routinely considered part and parcel of a legitimate Japanese martial arts practice. On the face of it, this is an extraordinary rehabilitation. As Chinese ideograms, these ‘Kanji’ characters can be read as follows: a) 禊 (xi4) is comprised of an upper and lower particle: Upper Particle = 气 (qi4) – refers to ‘energy’, ‘breath’ and ‘vital force’ Lower Particle = 米 (mi3) – denotes husked ‘rice’ that needs to be ‘cooked’ (transformed) in water Therefore, 禊 (xi4) suggests that the process of cooking rice in a cauldron (by lighting a fire underneath and boiling the water) not only produces nutritious food (which sustains all physical life) but also generates ‘steam’ as a useful and yet crucial by-product. This steam - through the (hidden) ‘pressure’ created - ‘lifts’ the lid of the cauldron with an effortless ease. It is this ‘unseen’ influence of a physical process that drives this concept. b) 祓 (fu4) is comprised of of a left and a right particle: Left Particle = 礻(shi4) is a contraction of ‘示’ (which denotes an ‘altar’ and the ‘rituals’ associated with it) – and refers to structured acts of ‘instruction’, that require ‘attention’ and possess great ‘importance’. Lower Particle = 犮 (ba2) denotes a ‘dog’ (犬 – quan3) that is ‘running’ (丿- pie3). The implied meaning is to perform a dramatic task with the appropriate amount of effort and required energy. This suggests that a religious ritual must be correctly performed (as if in a temple or at an altar) in the physical world - that opens a connecting door-way to the spiritual world. Once this channel has been correctly opened – the influence of the spiritual world is then allowed to positively flow (unseen) into the material world – thus influencing temporal events. Correct (disciplined) and timely action in the physical world is the basis of this concept. Success is defined as achieving an exact ritualistic replication that does not deviation from the accepted norm – as ‘deviation’ of any sort is tantamount to ‘ill-discipline’. Conclusion Armed with this knowledge, it can be suggested that the Japanese concept of ‘禊’ (Misogi) refers to arduous physical activity that requires ‘sweating’. Through hard and continuous labour – a definite and positive metamorphosis is produced in the material world – that possesses definite (but ‘hidden’) implications for the inner world (almost as a side effect). By way of comparison, ‘祓’ (Harae) refers to a metaphysical ritual that although partly physical in its ritualistic content, remains nevertheless ‘metaphysical’ in nature and intent. This is because ‘祓’ (Harae) constitutes a ‘purifying’ spell achieved through words, actions, and a specific and certain state of mind.

0 Comments

Dear Tony Interesting. Thank you for your knowledgeable explanation of sparring - an adult 'tiger playing with a cub'. This inspired me to research 'Ran-Dori' in Japanese-language sources - which is written as '乱取り' - '乱捕り' and 'らん‐どり'. Both of the following Japanese-language Wiki-entries (I have checked the data is correct) should be read side by side to gain an all-round clarity - as the 'Randori' entry does not specifically mention Karate-Do - whilst the 'Kumite' page explains that in some Styles of Karate-Do - 'Kumite' is referred to as 'Randori'. Randori - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate) Kumite - Japanese-Wiki (Fed Through Auto translate) I suspect the inference is that in Okinawan Karate-Do the term 'Randori' is used - whilst in Mainland Japan - the term 'Kumite' is the preferred. Difficult to say, but as you know, 'nuance' and 'implication' is an important part of Japanese communication. What is NOT said is as important (sometimes more so) than what IS said. Perhaps this Yin-Yang observation is just as important for sparring - whatever its origination and purpose. As for the traditional Japanese and Chinese ideograms - this is what we have: 乱取りand 乱捕り 乱 (ran) = chaos, disorder 取 - 捕 (to) = take hold of, gather, control, arrest り(ri) = logic, reason, understanding Therefore, 'Ran-Tori' and 'Ran-Dori' are synonymous - with the concept expressed in its written form as '乱-取り' - ot 'Chaos (Random Movement) - Seize Control of'. What is 'chaotic' in the environment is wilfully taken control of - by imposing an outside order upon it. This suggests that the 'non-controlled' is 'controlled' by the structure of Kata-technique - which is brought to bear by an expert. There also seems to be the suggestion that that which 'moves' - is wilfully brought to 'stillness'. As for a Chinese-language counter-part, perhaps we have: 乱 - 亂 (luan4) = disorderly, unstable, unrest, confused and wild (Japanese = 'turbulent') 取 (qu3) = take hold, fetch, receive, obtain and select り- 理 (li4) = put into order, tidy up, manage, reason, logic and rule It would seem that the Japanese term of 'Ran-Dori' equates to the Chinese term of 'Luan-Quli' - or 'Disorder - (into) Order Rule'. Your reply inspired me to think about what the Japanese '乱' (Ran) - or Chinese equivalent '亂' (luan4) - actually means. What is the definition of the 'disorder' being referenced to when 'Ran-Dori' is being discussed? Therefore, '亂' (luan4) is comprised of a 'left' and 'right' particle: Left Particle = 𤔔 (luan4) means to 'govern' and 'control' - and is structured as follows: a) Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. b) Lower (Inner) Element = 幺 (yao1) - a contraction of '糸' (mi4) which refers to 'thin silk threads'. c) Lower (Outer) Element = 冂 (jiong1) this is a 'comb', 'beater' or 'heddle' - a device to 'order' the silken threads that require weaving. In normal usage, this ideogram denotes the structured boundary that clearly demarks the city limits. Right Particle =乚 (yi3) is a contraction of '隱' (yin3) - meaning to 'hide', 'conceal' or 'cover-up', etc, as in 'something is missing'. It can also refer to a required process that is 'profound', 'subtle' and 'delicate' - but which is currently 'lacking'. It may also mean 'secret' and 'inward' or 'inner', etc. I would say that 'obscuration' is what this ideogram refers to in its meaning. Conclusion The literal meaning of '亂' (luan4) [or 'Ran' in 'Ran-dori] - is that it refers to a lack of skilful organising ability (disorder and confusion). The thin silk threads are not placed correctly on the wooden frame (loom) - and therefore cannot be 'weaved' together in an orderly fashion. This entire process lacks the required profound knowledge and experience to achieve the objective - thus the hands (and body) cannot be used in the appropriate manner. Ran-Dori (乱捕り), as a complete process, suggests that it is the opposite of the above 'lack of skill' that is require in sparring. Not only is this skill required, but 'ri' (li) element (理 - li3) - suggests a 'regulation' and an 'administration' (premised upon logic and reason) - such as the profound skill required to 'cut' and 'polish' jade. I was discussing Randori with another language expert and they gave me more data which I have added to this paragraph: 'Upper Element = 𠬪 (biao4) represents two-hands working together. The upper '爫' (zhao3) is a contraction of '爪,' (symbolising the vertical 'warp' threads used in weaving) - representing a 'claw' or 'hand' grasping downwards (from above) - and the lower '又' (you4) which is a right-hand 'grasping to the left' (meaning 'to repeat' and 'to possess') - signifying the horizontal 'weft' thread used in weaving. ' I was curious as to why the two hands were so specific in their orientation and my colleague said that they are clearly carrying out the process required for ancient 'weaving'. One hand is laying the 'warp' - or 'vertical' thread down through the loom - whilst the other right hand is performing the function of 'weaving' multiple 'weft' threads into place horizontally across the loom! As a matter of comparison - the 'Kumi' (組) in Kumi-te (組手) - Chinese 'Zu Shou' - means to 'weave continuously'. This translates as 'to be skilful' (the silken threads are skilfully woven [糹-si1] together forever - like the longevity of a sacrificial vessel [且 - qie3] - which are traditionally made out of stone). Therefore, Kumi-te literally refers to a 'continuous skill that unfolds through the hand'. This may be compared to the term 'Ran-Dori' which refers to a 'missing skill' that has yet to be 'acquired' and is in the midst of 'being acquired' (through developmental training) - whilst Kumi-te implies that the required skill is already present and should manifest automatically.

2023-10-17 Global Times Editor: Li Yan Lined up neatly, over 50 ancient explosive weapons were recently excavated at the Badaling Great Wall in Beijing. A total of 59 stone bombs were discovered by archaeologists along the western section of the Badaling Great Wall in Beijing’s Yanqing district. Ma Lüwei, an archaeologist specializing in ancient Chinese military history, told the Global Times that the stone bombs were major weapons used to “defend against enemy invasion” along the Great Wall during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). “The bomb was often installed in medium-sized hollow bits of stone. Those weapons were easy to make and were also very handy for soldiers to throw them down at invaders while standing on the Great Wall,” Ma told the Global Times. Shang Heng, an associate research fellow at the Beijing Institute of Archaeology, said the stone bombs possessed “big explosive power” and were once the preference of Qi Jiguang, a Ming Dynasty military general who made major contributions to China’s military system and strategy as well as the innovation of military weapons. Those 59 stone bombs were found inscribed with orders at one of the Great Wall’s station houses that were once used for standing guards watching out for the enemy. The space was later identified by archaeologists as a warehouse for storing weapons. Prior to the new discovery, no similar “warehouses” had been found along the Beijing sections of the Great Wall. Besides the weapon warehouse, other ancient buildings along the Great Wall, such as a “horse face” wall, an ancient wall used on the Great Wall that allowed soldiers to climb up and shoot arrows, were also discovered during the latest archaeological project. A stone fort that was once used to support cannons was also discovered along the Beijing Great Wall for the first time. Archaeologist Wang Meng told the Global Times that these relics shed light on the functions and design planning of the Great Wall. The new discoveries at the Badaling Great Wall reflect China’s continuous research and conservation efforts concerning the Great Wall. Taking Beijing for example, between 2000 to 2022 more than 110 project were carried out to preserve the Beijing section of the Great Wall, which is known for having the most complex buildings and geological conditions compared to other Great Wall sections such as those in the provinces of Hebei, Gansu and Shaanxi. Twenty-two years of conservation efforts have achieved a great deal. In 2021, a project aimed at rescuing the Liugou section of the Great Wall in the Yanqing district helped identify exactly how the Ming Dynasty Great Wall was constructed. A year later, ancient everyday objects such as plates, scissors and bowls were discovered along the Jiankou section of the Great Wall, providing insight into the daily life of soldiers stationed along the wall. “The Great Wall holds value not only for its remarkable architecture, but also the cultural and historical connections to ancient Chinese people’s lives, their unity as well as their spirit,” historian Fang Gang told the Global Times. Among all the projects, the Great Wall National Cultural Park, scheduled for completion in 2035, is China’s blueprint for integrating Great Wall resources nationwide into one landscape. The strategy aims to preserve the legacy of the Great Wall, while also extending its reach into fields such as cultural tourism. A total of 37 provincial-level planning projects have been carried out so far in 2023. A total of 16 have been completed, including one to promote the establishment of Great Wall museums in Qinhuangdao, Hebei Province. English Language Text: https://www.ecns.cn/m/news/culture/2023-10-17/detail-ihcuappp4688434.shtml

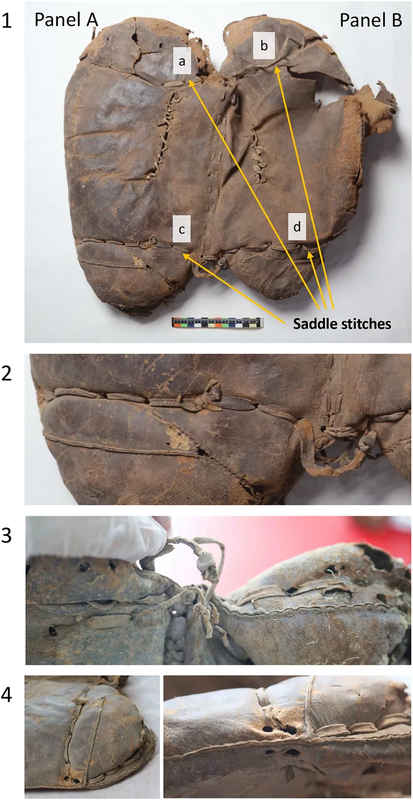

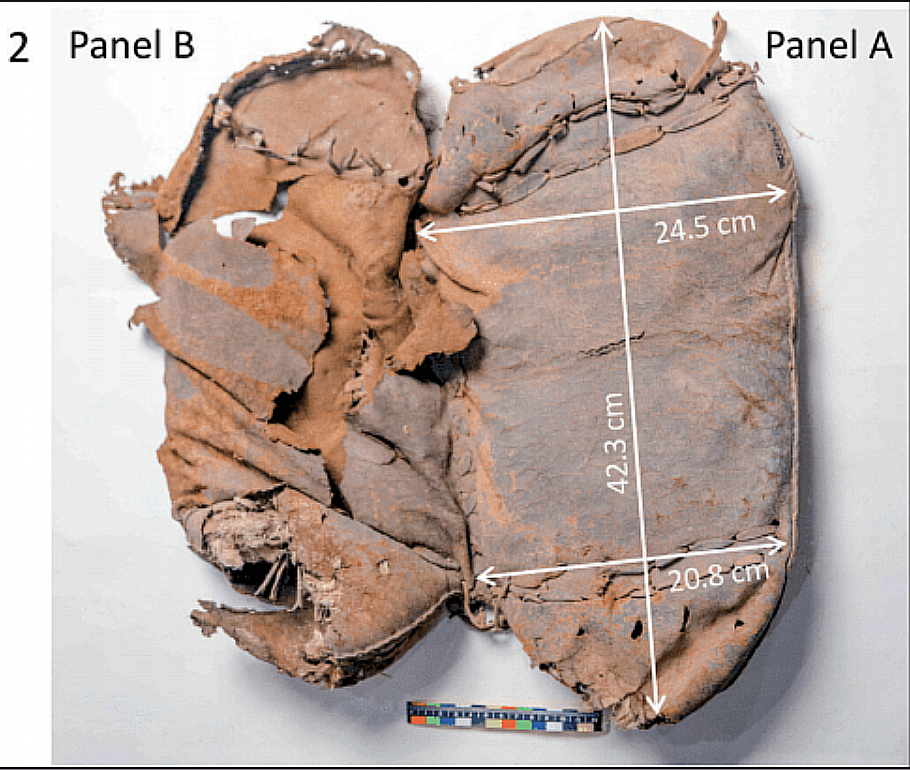

Dressed in a hide coat, wool pants, and leather boots, the rider was buried with her saddle “placed on her buttocks as if she was seated on it,” the team note. And it clearly isn’t just for show: the saddle shows “[o]bvious traces of repair,” they write, showing that it was “intensively used and maintained” throughout its lifetime. Recently, an international archaeological team discovered the earliest known saddle at an excavation site in China. The saddle was found in a tomb in a cemetery in Yanghai, Xinjiang, China. The tomb was built for a common woman who was wearing what seems to be a 'saddle' - positioned so it looks as if the deceased person was still sitting upon it - as if in life. Research shows the tomb owner and saddle are from about 2,700 years ago. Previous research has found that the domestication of horses first occurred around 6,000 years ago, although during the initial stages of domestication, the animals were used solely as a source of meat and milk. It is thought that horse riding took another 1,000 years to develop. Shortly thereafter, riders began looking for ways to cushion the forces of riding. Researchers believe saddles likely originated as pads strapped to a horse's back. The saddle found is constructed externally from cowhide and is internally padded using deer and camel hair - as well as straw filling. This saddle was designed to assist riders sit with greater stability whilst sat on horseback - so that arrows could be fired from a bow with greater accuracy - whether the horse was standing still or engaged in movement. There are no stirrups on this Xinjiang saddle - as is to be expected. However, a simple stirrup has been found in ancient India dating to the 2nd century BCE - but stirrups were not used by the Greeks or Romans and did not appear in Europe until the 8th century CE. This saddle found in China predates the ancient saddles previously found in the Central and Western Eurasian Steppes. The earliest known saddles date back to between the 5th-3rd centuries BCE - leaving researchers to conclude that China is the earliest known civilization in the world to have designed, made and used saddles. Chinese Language Text: English Language Text: 2,700-Year-Old Saddle Found In Ancient Chinese Tomb Is Oldest Ever Discovered

Part of educating ourselves (and our children) - has involved the continuous stimulation of mind and body through visiting museums, examining the past and striving to understand humanity as a broad expression of culture and creativity. During 2018, myself, Gee, Mei-An and Kai-Lin visited Torquay Museum (in South Devon). Astonishingly, this place has a Medieval Japanese Battle Kite! Oddly, I believe this object has been subsequently 'returned to storage' not long after our visit - and despite enquiring - I could not find out any further data as to provenance. An Imperial Archer (the Medieval equivalent of Early Japanese 'Special Forces') would be 'affixed' to the centre of a large (bamboo) kite and extended (through the use of a rope anchored to the ground) around 200 feet into the air above the battlefield. Sniping with arrows would then ensue - whilst the position of the enemy would be relayed to the Command on the ground! The kite could be moved with the soldier kept up in the sky if the terrain, weather and enemy activity allowed. What these individual soldiers went through whilst having to stand on such a flimsy device - we can only speculate! Their bravery, however, must be beyond doubt!

In the aftermath of the Xiamen “Chopping” incident – the victim Shi Jiaming (石佳明) is NOT dead – and thanks to advanced Chinese medical care and world-class surgery, his hand has been carefully re-attached and he is well in hospital! 1. Reviewing the “Chopping” Incident! On May 23rd, 2023, an astonishing “chopping” incident occurred on a college campus situated in the Xiang'an District area of Xiamen City, Fujian province (a place world renowned for its martial arts culture). Shi Jiaming - a Douyin ‘Influencer’ - was holding an outdoor “live” broadcast together with another well-known internet celebrity named ‘Ye Jianan’ (叶建安) when he was suddenly attacked by a man in black wielding a bladed weapon (Police photographs suggest the weapon used was a ‘Wakizashi’ - or traditional Japanese ‘Short-Sword’ usually worn with the ‘Katana’ or Japanese ‘Long-Sword’). During the fray - Shi Jiaming's left hand was cut off - whilst he and Ye Jian'an quickly fled the area – running for their lives! After the incident, the Police quickly apprehended the potential murderer – whose surname is ‘Luo’ (罗) - and sent the injured Shi Jiaming to the hospital for treatment. It is reported that the cause of the incident was a quarrel between Luo and Ye Jianan. Luo is from Sanming City, Fujian Province. He used to find a sense of ‘presence’ and ‘well-being’ in Ye Jianan's live broadcast chatroom - but was recently ridiculed and insulted by Ye Jianan. Feeling resentful - Luo took a bus from Sanming City to Xiamen and waited in ambush outside the college cafe. As Luo did not know who Shi Jiaming was – he mistook him for Ye Jianan's accomplice (and bodyguard) – and so attacked him! There were rumours on the Internet that Shi Jiaming could not be saved and had died. Obviously, these false ideas are not true. 2. The Hand Was “Surgically” Re-Attached! Fortunately, Shi Jiaming did not die due to excessive blood loss as falsely speculated by a number of people online. After emergency treatment by doctors - his severed hand was successfully re-attached, reset and fixed. The doctors stated that the cut was so ‘clean’ and ‘exact’ that it was easier to repair than if the cut had been haphazard or ‘jagged’ due to inexperience. This suggests Luo has had considerable martial arts experience with ‘foreign’ bladed weapons. Currently, Shi Jiaming is out of danger and is recovering. According to the doctor, if there are no complications (such as infection or rejection after the operation), he has a good chance of recovering all his hand function. Netizens expressed shock and outrage at the incident. Some people condemned Luo's cruelty and unreasonableness, some sympathized with Shi Jiaming's experience and loss, whilst others criticized Ye Jian'an irresponsibility and apparent cowardice in the face of danger. Some people also called for strengthening Internet usage regulations and legal education to prevent similar tragedies from happening again. Chinese Language Article: 厦门砍人事件后续,石佳明没有死,手已经接上,人在医院安好 2023-05-25 22:42

一、事件回顾 5月23日,一起惊人的砍人事件发生在厦门翔安区某学院内。一名抖音网红石佳明正在和另一名网红叶建安进行户外直播时,突然遭到一名持刀的黑衣男子袭击。 石佳明的左手被砍断,和叶建安夺路而逃。事发后,警方迅速出动,将凶手罗某抓获,并将受伤的石佳明送往医院救治。 据悉,这起事件的原因是罗某和叶建安之间的口角矛盾。罗某是福建三明市的人,曾在叶建安的直播间中找存在感,却遭到了叶建安的嘲讽和辱骂。罗某心生怨恨,从三明市乘车来到厦门,在学院咖啡厅外埋伏等待机会。由于不认识石佳明,罗某将他误认为是叶建安的同伙,便对他下了毒手。 有网络谣言说石佳明救不回了,已经死亡。 二、手已经接上 幸运的是,石佳明并没有因为失血过多而死亡。经过医生的紧急抢救,他的断手被成功接上,并进行了复位和固定。 目前,他已经脱离了生命危险,正在恢复期。据医生介绍,如果术后没有感染或排异等并发症,他有很大可能恢复手部功能。 对于这起事件,网友们纷纷表示震惊和愤慨。有人谴责罗某的残忍和无理,有人同情石佳明的遭遇和损失,有人批评叶建安的逃跑和不负责任。也有人呼吁加强网络文明和法制教育,避免类似的悲剧再次发生。 As regards 'tradition', 'lineage' and 'respect' - these are aboth fundamental Chinese cultural aspects which were brought suddenly into the modern world in 1911 (the ‘Nationalist’ Revolution) and 1949 (the ‘Socialist’ Revolution). In Japan, this process began with the Meiji Restoration of 1868. This all evolves around the concept of 'face' (面子 - Mian Zi) - or the ability to walk through the public spaces with one's dignity fully intact and face on display. To traverse the public spaces used to demand a stern adherence to the teachings of 'Confucius' as defined by various philosophers and politicians, etc. Indeed, Confucianism regulated not only the society of China for over two-thousand years, but also many other countries including Korea, Japan, Vietnam and Okinawa (including large areas of South-East Asia). Furthermore, wherever Chinese people have migrated - Confucianism has followed. Confucianism still defines Chinese society, but the way this happens has evolved over the centuries and can still seem baffling to the uninitiated. Regardless of this, understanding ‘Confucianism’ is the only way ‘in’ and ‘out’ of a Chinese cultural grouping. In the old days, breaking these rules led to the breaking of one's body - a simple correlation between spiritual morality and physical punishment. The individual body used to be the property of one's parents and belonged to the State (that is to the 'Emperor'). The body of a child used to represent the continuation of a family's ancestral 'Qi' energy and the lasting of the Clan Surname. Judicial execution often involved public beheading (the 'loss' of face through the loss of the head) – a punitive process which usually including the killing of all members of the same family (depending upon the severity of the offense). Social execution involved the 'exclusion' of an individual and a family (Clan) - from all meaningful social interaction. It is interesting to note that despite the differences in political and economic view that exist between Beijing and Taipei, for instance, Chinese people living in Taiwan and Mainland China would agree (both implicitly and explicitly) about what 'face' is, and about what 'losing' and 'saving' face actually entails - so important is this central aspect of Chinese culture. Today, the forces of modernity have radically redefined this tradition - but occasionally murders and beatings do still occur throughout Chinese society - usually involving disputes regarding love affairs, relationship betrayals and intimate deviations, etc. Of course, if an individual is known to have behaved in a terrible fashion for whatever reason, social ostracization tends to follow. Remember, China is comprised of 56 ethnicities which enlarged through the Chinese diaspora as it intermixes with different people throughout the world. This means that 'saving face' and 'losing face' tends to vary in interpretation. For instance, my modern academic colleagues in China tend not to give 'face' much consideration - but the older members of our Chinese family still live their lives by this concept! Okinawa, for instance, is still being punished by the Mainland Japanese for being historically ‘Chinese’ – and this has involved the post-1945 US Military Bases being lodged of the Island. This US neo-imperialist presence has been compounded by an assault on Ryukyu culture that has been intended to eradicate all obvious ‘Chinese’ cultural tendencies and replace these with a blend of Americana and Nipponisation. Yet the robustness of the Okinawan way of life stands inherently strong – with an older version of ‘Confucian’ ideology lurking firmly in the background and regulating the martial arts, leisure and business communities. Indeed, the Chinese concept of 'face' (面子 - Mian Zi) literally translates as 'Face Child' or 'Face Master'. The second ideogram '子' (zi3) means 'a child that is born already old and wise' - and is associated with 'Laozi' (老子) - one of the founders of Daoism. Perhaps 'Saving Face' would be better redefined as 'Preserving Face'. In England we talk of proudly holding our heads-up high in public.. Of course, in the strict Confucian model, the onus is on the individual rather than the social collective. Today, the social collective is just as responsible as the individual - so that the entirety of society works together to preserve the status quo. Now, it is as if the collective society has its own 'face' that has to be preserved in the 'face' of individual behaviour. It is a two-way street. Individual responsibility is now balanced with collective responsibility - creating a preserving 'tension' of positive interaction. An individual's 'face' is considered secondary and is only saved when the 'face' of orderly society is acknowledged and preserved. Having explained all this, there still exist pockets of Chinese culture spread throughout the world that uphold older versions of ‘Confucian’ ideology and expect all incomers to understand and respect this reality.

Etymology of ‘Gedan Barai’ (下段払い) - or ‘Gedan Hara-I’ Dissecting the ‘Lower Block' of Karate-Do!3/8/2023 I was asked a while ago to look into the etymology of the Karate-Do self-defence technique of 'Gedan Barai' - once by a British student (who had attended an advanced Japanese language course as he is a Solicitor) - and again by a Japanese student who was passing through the UK and had visited a few Dojos - saying some 'sounds' of the names of the techniques being used did not seem correct: My view is that this transmission of culture is a) ongoing (and therefore a continuous process), and b) is a two-way street which must involve forgiveness and understanding. We must all help one another until our mutual understanding is correct. What is interesting is how philosophically different the 'Lower Block' is treated within Karate-Do compared to the 'Middle' and 'Upper' Blocks (which are explained merely as mechanical devices and not associated with the 'Conception Vessel' they pass through)! It is as if the 'Lower Block' is from a very old martial ritual! Finally, I was once told that the 'Lower Block' is not just a 'parry' or 'check' of an incoming attack - but is also a simultaneous 'Hammer-Strike' to the opponent's groin-area. Interesting food for thought.

Dear T

With regard to 'Muchimi' (ムチミ) - 'heaviness', 'rooted': When I was younger (and less experienced in translation), I probably would have been tempted to read the Japanese (Katakana) character of 'チ' (chi) - or 'one thousand' - as being related to the Chinese ideogram of '手' (shou3) - meaning 'open hand' (and to 'clutch', etc), as they look very similar in structure. My instinct would have led me in this direction considering the martial arts usage related with the term 'Muchimi' - applying a logical 'reverse chain of events', so-to-speak (in other words - 'working backwards' using logical association). However, all the multi-language dictionaries I have access to today - strongly suggest there is no connection between these two characters. As this possible association played on my mind (in the sense that no stone should remain unturned), I checked '手' (shou3) in these dictionaries (focusing on the 'Japanese' variants) and found that even today - the Chinese ideogram of '手' is still often used - 'unchanged' - within Japanese script, usually rendered as 'te' or 'shu', etc. When '手' is modified within Japanese script - it is presented as 'テ' (Katakana) and 'て' (Hiragana) - pronounced 'te' and 'shu' respectively. Therefore, although the 'チ' (Katakana) character found within 'Muchimi' (meaning 'one thousand') is 'similar' to the (Katakana) character 'テ' (te) - meaning 'open hand' - as you can see, there are slightly different upper structural differences - despite a certain lower level similarity. After further studying the history of each of these specific Japanese (Katakana) characters - the lower similarity appears to be purely coincidental rather than deliberate. The conclusion being that there is no connection between the 'チ' (Chi) - one thousand -Japanese (Katakana) character and the '手' (shou3) - meaning 'open hand' - Chinese ideogram. Best Wishes Adrian This is a very rare 'Hui' (Muslim) martial art - developed and practiced within China by descendants of Arab merchants (and travellers) who settled in China around a thousand years ago (and at other times after this date). These men were generally highly respected by the Chinese Authorities and often married Chinese women - altered or changed their surnames to fit-in - and sired 'Chinese' children often brought-up within the Islamic faith. This martial art was developed by three respected Imans serving in the Bozhou (亳州) Mosque of Beijing during the reign of Qing Dynasty Emperor Daoguang (r. 1813-1820) and is comprised of various Chinese martial arts techniques as gathered by Hui people living primarily in the Henan, Anhui, Shandong areas - as well other places: If I am reading this name correctly (see HERE for more information), this art is emphasising intellectual and physical study (晰 - Xi), a process which builds 'Yang' (阳) energy which represents the 'sun' or 'brightness' (the literal meaning of 'Yang') represented by Allah! As Muslims only practice for self-defence the 'open-hand' or 'palm' (掌 - Zhang) is emphasised over the closed fist. Yin and Yang are developed equally with the inner and outer body being made strong and healthy so that the practitioners can a) pray properly and recite the Holy Qur'an in the Mosques, b) perform wholesome labour properly within society and c) maintain the strength to carry-out charitable work and help others free of charge. As this art builds outer strength for praying and inner strength for recitation - by cultivsting Yin and Yang (using martial techniques derived from at least three other provinces) - it is also known by the name of 'Three Considered Profundities' (三议妙 - San Yi Miao). The art itself must only be used to protect vulnerable individuals (including the practittioner) from attack (or 'insult') within society - but the rules for this are very strict (Halal).

|

AuthorShifu Adrian Chan-Wyles (b. 1967) - Lineage (Generational) Inheritor of the Ch'an Dao Hakka Gongfu System. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed