a) 追 (zhui1) - Japanese Kanji (ou) = chase, follow and pursue

b) い (I) - Japanese Hiragana = 'to do' (verb) as in '追い払うこと' (Oi harau koto) or to 'drive something away'

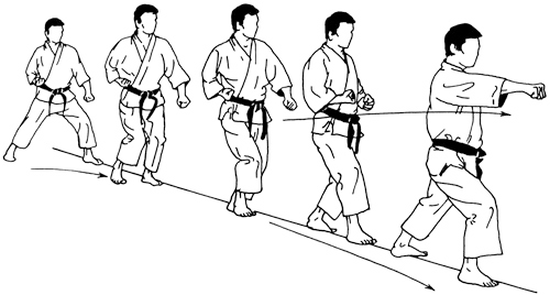

This seems to suggest that an 'Oi Tsuki' is a leading punch which (fluidly) follows the movement of an enemy target (similar to - but not identical with - a Western Boxing 'Jab') - and is used to 'drive' the opponent away! There might also be an implication that this punch 'follows' the opponent and then is 'driven' through their centre of mass using immense 'penetrating' power!

Within the Wado Ryu Karate-Do tradition 'Oi' (追 い) is replaced with the Chinese ideogram '順' (shun4):

1) 順 - Japanese Kanji (also written as 'じゅん') and pronounced 'Jun' - meaning 'order', 'sequence' and 'obedience'

The Chinese ideogram '順' (shun4) is comprised of two constituent particles:

i) Left-hand particle = '川' (chuan1) - river, flow and direction

ii) Right-hand particle = '頁' (ye4) - head, top and beginning

Therefore, the use of '順' (shun4) within the context of a 'Jun Tsuki' - refers to a 'leading' (as 'head' equals 'forward') and 'penetrating' punch (like a torrent of rushing water hitting and overcoming an obstacle) which follows closely the movement of the opponent. However, as with all these concepts - a play on words might be in operation. It could be that a continuously 'flowing' punch strikes at the spiritual and physical origin of an opponent ('driving' through their literal and metaphysical centre, so-to-speak) - thus rendering them useless and unable to respond.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed